The South African

The South African

* Anton Pelser Archaeological Projects

** Amafa aKwaZulu-Natali

In July 2012, during trenching work for the erection of palisade fencing around their depot in Bergville, the Department of Transport came across an ammunition cache of unspent cartridges. They immediately sent for the South African Police Service (SAPS) in Bergville to investigate the find and the munitions were, at first, destined to be destroyed. Amafa, the provincial heritage resources agency, issued a stop order. An initial inspection by a staff member determined that this discovery dates to the AngloBoer War (1899-1902). The site is located on the Department of Transport's depot lot, adjacent to the Bergville Primary School.

During a subsequent site visit, the authors were puzzled by the large number of river pebbles among the exposed cultural artefacts. After visiting the existing blockhouse in town it was proposed that the ammunition cache might be located on the site of yet another British blockhouse which formed part of a line of fortifications during the War, set along the Tugela River.

This resulted in a rescue archaeological investigation of the site which was conducted during a three day period in August 2012.

Historical background

The history of the Anglo-Boer War (1899-1902) is well known and researched and will not be discussed here in any detail. It would suffice to say that the finds and site should be interpreted against this background and also in terms of the blockhouse system employed by the British during the War.

The Bergville area played an active role during the War. One of the Anglo-Boer War's most important and bloodiest battles was fought at Spioenkop between 24 and 25 January 1900 (Packenham, 2009, p 305); Spioenkop is approximately 18km north-east of Bergville. The conventional phase of the Anglo-Boer War ended after the capitals of the two Boer Republics - Bloemfontein and Pretoria - were taken over by the British, respectively on 13 March 1900 and 5 June 1900 (Pakenham, 2009, pp 391,453) and the last pitched battle of the war, Bergendal/Dalmanutha was fought near Belfast between 26 and 27 August 1900 (Pakenham, 2009, p 476).

After these skirmishes the Boer forces started their less conventional, guerrilla warfare, tactics that protracted the war and frustrated the British for nearly two more years before the final signing of the Peace Treaty of Vereeniging on 31 May 1902 (Pakenham, 2009, p 591). In order to prevent the Boers from attacking rail and other communication lines, the British themselves started to employ restrictive tactics to curb the smaller, mobile, Boer commandos, such as the erection of lines of blockhouses and barbed-wire entanglements across the country. These were maintained from June 1900 to the end of the hostilities.

From mid-1901, the drives and raids directed against the mobile Boer units were increasingly facilitated by static aids like the barbed wire and blockhouses. Initially, ineffective trenches centred on vital points, such as stations and bridges, were replaced at intervals with stone forts and corrugated blockhouses manned by permanent garrisons to guard the tracks. These were connected by telephone and barbed-wire fencing. Major Rice of the Royal Engineers invented a cheap, mass-produced blockhouse. Due to its easily erectable structure, the intervals between the blockhouses could be reduced to about 1 km and later, to less than 185 metres in some sections. Eventually some 8 000 blockhouses were constructed, manned by 50 000 troops and about 16 000 black scouts (Boyden et al, 1999, p 375).

Blockhouses

Termed the 'Rice-pattern blockhouse', it initially consisted of a wooden frame with corrugated iron sheeting fitted to both sides of the frame, with the space in between packed with shingle (stones). Eight frames, with loop-holes, were fitted together to form an octagonal blockhouse. Rice eventually introduced the circular blockhouse using precurved corrugated iron sheeting. The circular pattern was easier to manufacture and transport, required less material, and was simpler to assemble in the field. The octagonal type took eight days to erect while the circular type took only three days and was also stronger. The circular blockhouses soon became the general pattern, and factories were established at inter alia Middelburg, Pretoria, and Bloemfontein, where it was prepared and dispatched ready for erection when required (Boyden et aI, 1999, p 375).

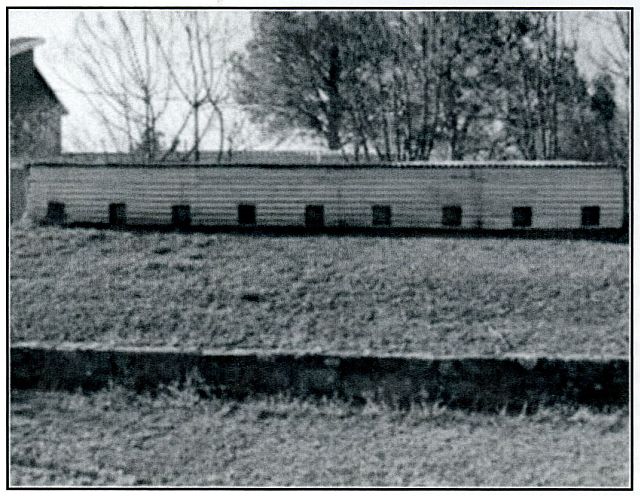

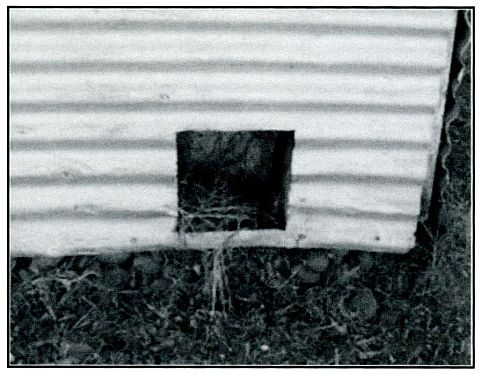

The existing blockhouse in Bergville is of a slightly different type or style than the 'Rice-pattern blockhouse', albeit with similarities (Fig 1). According to the National Monument plaque, it was built in May 1901 by the British during the Anglo-Boer War, one of a series to protect the Upper Tugela drifts. It is currently used by the MOTHs (Memorable Order of the Tins Hats) as base and as a result is fairly well preserved. It is not certain how much has been changed over the years in terms of its construction, but it clearly had corrugated iron sheeting (possibly covering a wooden frame and earthen walls) filled with 'shingle' (in this case round river pebbles) for extra protection (Fig 2). Its shape is square, and its floor is sunk to below the level of the fitted loopholes. An earthen wall surrounds the structure, and it is possible that .sandbags and barbed-wire might also have been used.

Research

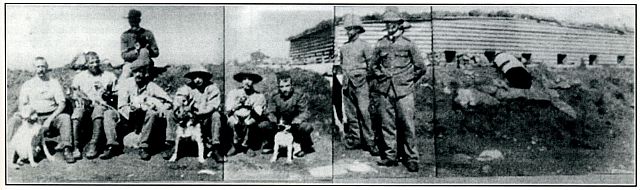

A collage of old photographs (see Fig 3 below), dating to the Anglo-Boer War show another blockhouse of the same type located in the Bergville area. Visible is the blockhouse, its garrison, a tented camp and local scenery. The captions for these photographs read: 'Anglo-Boer War: British Blockhouse at Bergville. Two Tommies are standing front, left, while a further Tommy crouches (left) holding his dog', and 'Anglo-Boer War: British Blockhouse at Bergville. Two Tommies with helmets on are standing front, left' (NAB, Ref C4978 & C4979).

The dates assigned to these photographs are 1900, but this is probably incorrect since the blockhouses along this line were only erected in May 1901.

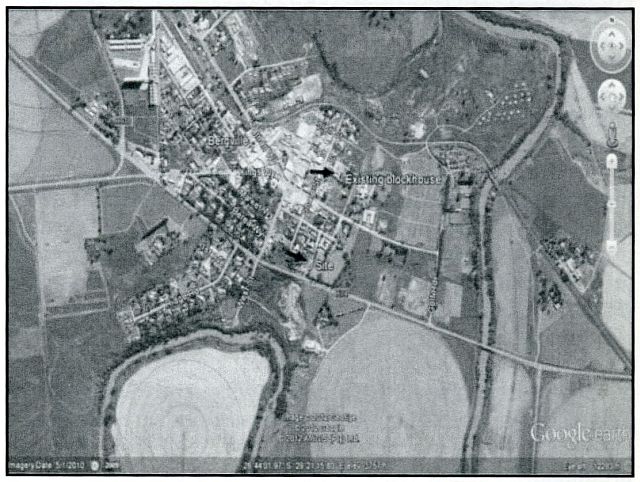

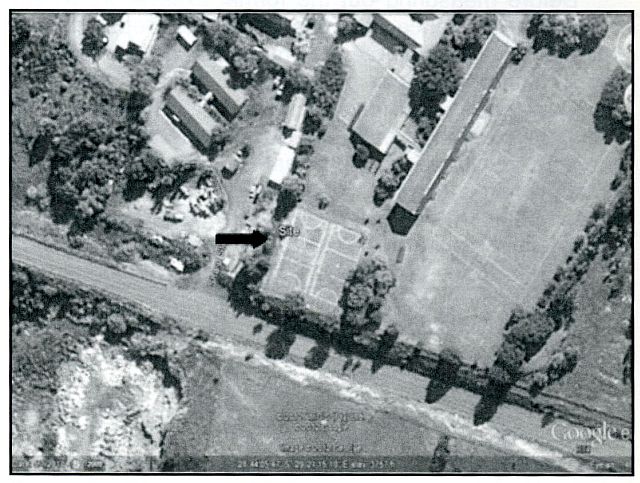

There is some doubt whether the blockhouse in these photographs is the same one still standing in town, but it is clearly of the same type. During the excavation of the site, photographs of the surrounding hills (visible in the historic photographs) were taken from various angles, and it seems unlikely that the Bergville blockhouse is the one photographed, although it is possible that the photographs were taken from approximately the position of the excavated site. The site where the ammunition cache and other material was found and excavated is located on a slight outcrop overlooking the road to Winterton (R74) and the Tugela River. The location of the two structures in relation to each other is shown in Figure 4. It is possible that, at the time, there was also a drift across the river. The Bergville Primary School, and more specifically its netball court, is placed roughly in the location of the earlier blockhouse (Fig 5). Evidence of this structure, including the munitions cache, was found during the excavations and it is possible that this section was on the periphery of where it would have been standing.

Figure 4: An aerial view of the area (Google Earth 2012, Image date 5/1/2010),

arrows showing existing blockhouse and new site.

Figure 5: A closer view of the site's location, showing the school's netball courts

(Google Earth 2012, Image date 5/1/2010)

Archaeological investigation

The archaeological investigation of the site focused on the area where the fencing post pits were excavated by the Department of Transport, and specifically those which exposed the unspent .303 cartridges and other cultural material. During the earlier site visit, some in situ material (remnants of cartridge cases) were noticed in two of the pits, and the excavations therefore concentrated on this area. The aim was to recover any possible remaining bullets and in situ cultural material, while also trying to find evidence of the presence of a blockhouse. Cultural material (corrugated iron sheeting fragments), exposed during the development and kept at the SAPS Bergville offices, seemed to point to this possibility, while local MOTH members could remember a blockhouse at that location at some point in the past.

Mapping

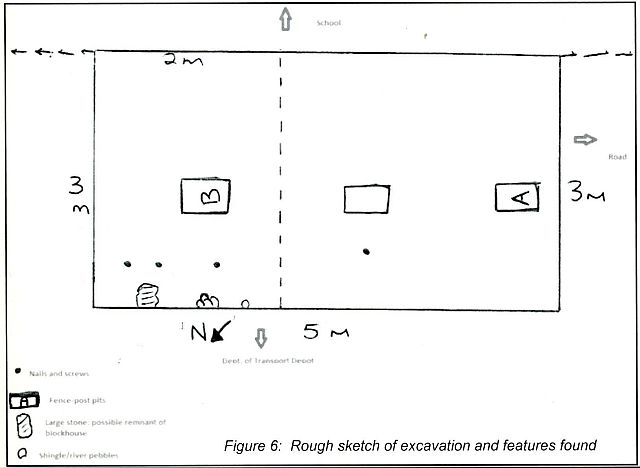

A hand-held Garmin GPS device was used to plot the site and excavations on Google Earth, while a basic hand-drawn sketch of the excavation block and features was also produced.

Excavations

Before measuring out the formal excavation, all soil heaps from the fence post pits left by the Department of Transport where cultural material was recovered, were sieved to find objects possibly left behind when the material was removed and taken to the SAPS. All these objects were sampled and documented as surface material. It included more unspent cartridges, fragments of cartridge cases (metal, wood and screws), glass bottle pieces, fragments of cartridge wrapping and pieces of corrugated iron sheeting (blockhouse remains).

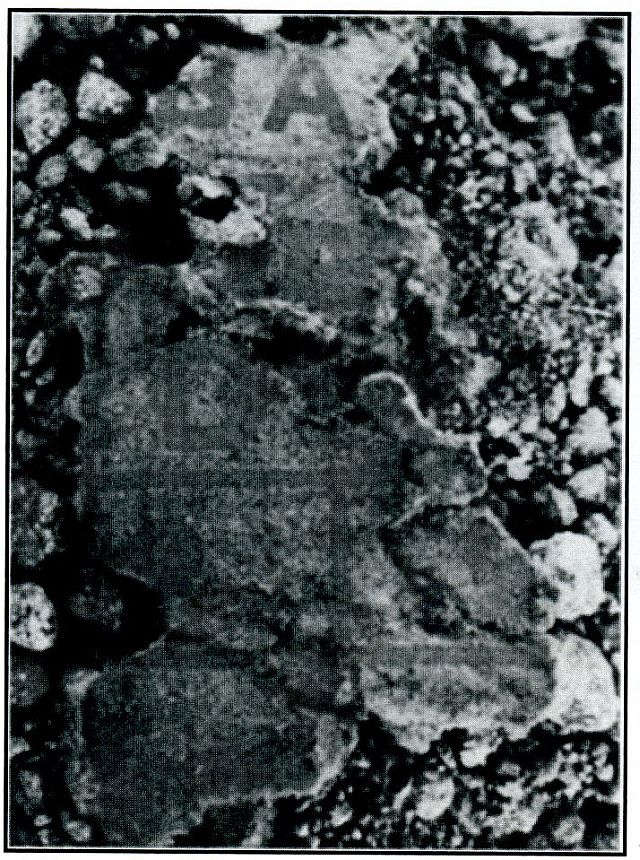

A 5m x 2m trench (Fig 6) was measured out over the two fence post pits where cultural material (cartridges) were recovered, directly bordering the existing fence between the school and Department of Transport property. The surface of the trench was first cleaned and levelled in 10cm spits, which uncovered more glass and other material. More evidence for the presence of a blockhouse was discovered in the form of shingle as well as roof-type screws and washers (Fig 7) similar to ones seen in the corrugated iron sheeting of the existing blockhouse in town.

The fence post pits (Pits A and B) in the excavation trench, where cultural material was recovered, warranted further investigation since in situ remains of ammunition cases and some cartridges were visible in these pits. Recovered from Pit B were more cartridges and an ammunition case (in the form of metal fragments, wooden pieces and screws from the corners of the case). The bottom of the case was excavated approximately 0.35m from the original surface level. In Pit A, located approximately 3m from Pit B, only a small section of another case was visible.

Once the trench area was levelled, the excavations continued up to the level where shingle and cultural material were still in situ, where these objects were photographed and their positions in the trench indicated.

Upon removal they were bagged and labelled for analysis. A 2m x 2m square was then measured out over the Pit B area before being excavated up to the level of the bottom of the ammunition case. More nails, screws and washers were recovered as well as river pebbles together with a sizeable sandstone block which could have been part of the original blockhouse base. The nails, screws and washers were aligned more or less in a straight line, close to the edge of the excavation and in relation to the shingle; further evidence of there having been a blockhouse on this site.

In the 2m x 2m block next to Pit B very little material was discovered except more pieces of the ammunition case. The rest of the excavation was levelled up to the level of the natural sandstone base rock. It seems as if the pit for the ammunition easels were dug through this layer and then possibly covered again. The same scenario was evident in the Pit A area where a 1.5m x 1.5m block was measured out around the pit. Again a sandstone base was discovered and the ammunition case seemingly put in a pit dug through this layer.

Results

From analysis of the cultural material recovered from the site and the archival documents (photographs), it is obvious that the site and associated objects date to the early twentieth century and, more particularly, the Anglo-Boer War (18991902). Moreover, there is sufficient evidence to prove that the site represents the remnants of another British block- town, erected in May 1901 as part of a row of blockhouses. The finds consisted of fragments of corrugated iron sheeting, roof-type screws and washers, nails, 'shingle' and the frame of the blockhouse.

The location on the crest of a ridge was perfect for a blockhouse, overlooking the road to Winterton and the Tugela River. During the War years, this probably represented a main transport route as well. Over time, the site has been almost completely destroyed. Most of the corrugated iron sheeting was removed and probably re-used somewhere else very soon after the Anglo-Boer War, while the building of the school in 1915, and the netball courts in later years, destroyed the remainder of the site to a large extent. The school's netball courts probably cover most of the original site, while the section where the excavation was focused and the cultural material recovered is likely on the edge of the structure. The reason for the large number of unspent cartridges (nearly 6 000 in total), still in their wrapping and metal cases is more difficult to explain. From the evidence in the excavation, the cases were stored in pits dug through the 'floor' of the structure into the natural sandstone layering. The reasons for it being left behind and forgotten will probably never be known. Similar examples of British ammunition caches dating to the war have also been found at Ifafi, near Hartebeestpoort Dam in the Northwest Province (Van Vollenhoven et al 2001), and at Steynsburg in the Free State (Bester, 2003, p291).

Discussion of Cultural Material

Although a fairly large amount of cultural material was recovered during the construction operation and the formal archaeological excavation that followed, most of it comprises unspent .303 cartridges. In total nearly 6 000 cartridges were recovered, with just more than 5 700 having been removed by the SAPS and kept in storage by them. In addition to the cartridges recovered during the fencing done by the Department of Transport, fragments of metal ammunition cases and 'corrugated iron sheeting were also removed by the Department and the SAPS.

During the authors' first site visit and the formal archaeological excavations, cultural material was also collected from the surface of the site. This included cartridges, fragments of cases and corrugated iron sheeting, glass bottle pieces and pieces of paper cartridge wrapping (Fig B).

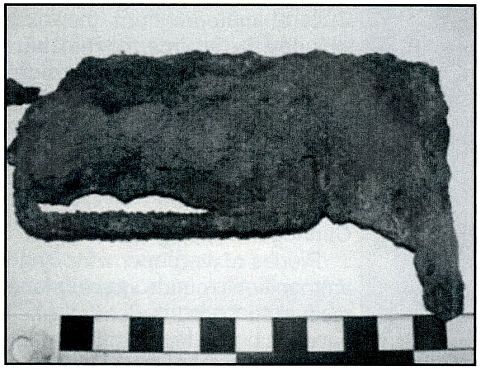

Cultural material from the excavations included in situ cartridges, ammunition case remains (Fig 9), corrugated iron sheeting, bottle glass, nails, roof-type screws, washers, and some unidentifiable metal objects.

Cartridge wrapping

Pieces of the paper wrapping in which ammunition rounds were placed were recovered from the general site and excavations together with fragments of the " ~ metal cases, which includes pieces of ~ wood and screws (Fig 10). The remains of one such case (basically the bottom of A- . the case) were found in situ in one of the pits.

The .303 cartridges were usually wrapped in a length of thin paper before being encased in a light-brown paper wrapper, with a thin blue string tying it together. The contents of a packet of ten rounds were indicated by red lettering. These packets were then neatly placed in a metal box, with each box containing around 1 400 rounds (Bester, 2003, p 291). The fragments of light-brown paper found on site have red lettering on it and, although not complete, the full lettering would have read: 'CARTRIDGES SA BALL .303 Inch CORDITE (then a number) Mark 11'.

Cartridges

Nearly 6 000 unspent .303 rifle cartridges were recovered from the site; 162 of them during the formal archaeological excavations. This number equates to close to four full cases of bullets. The cartridges are in a remarkably good condition, while fragments of paper wrapping still adhere to some of them. The head-stamp marking on all the cartridges is 'RtLC II', identifying the manufacturer as the 'Royal Laboratories', located in Woolwich in England. This dates the cartridges to the Anglo-Boer War period (Bester, 2003, p290). The cartridges had round-nose, cupro-nickel jacket bullets (Bester, 2003, p295).

Bottle glass

The bottle glass fragments were identified as that of rum or beer, possibly whiskey and soda, or mineral water bottles. Five of the fragments contain the partial names of the manufacturer or trader. Four of these only have single letters on them and are difficult to decipher. One of the mineral water bottle fragments displays the letters ' ... LAD .. .', which could perhaps refer to Ladysmith. However, this cannot be determined without a doubt.

One fragment, with the largest number of decipherable letters reads 'AER-AT[ED] MANU[FACTURERS]' but it cannot be determined who the trader or manufacturer was or where the bottle originated from.

Two fragments of a glass bottle top identify it as being part of a marble-stoppered mineral or soda water bottle dating to the late nineteenth or early twentieth century. These bottles are sometimes referred to as Codd-type bottles, after Hiram Codd, who invented the marble-stoppered bottle and patented it in 1870 (Lastovica & Lastovica, 1990, p26).

Nails, screws and other metal objects

As mentioned earlier, pieces of corrugated iron sheeting, rooftype screws and washers (to attach these sheets to the frame of the blockhouse), as well as a number of nails were also recovered. Other metal objects found include the remains of what might be a file and a hooped piece of metal flat bar that could have been part of a drum or similar object. overlooking the R74 to Winterton, and the Tugela River to the south and west of it, makes it the perfect position for a blockhouse. The Bergville Primary School's netball courts are more than likely positioned on top of the rest of the original blockhouse site. Archival photographs of a blockhouse in Bergville also identified this site as the most likely location for the specific structure.

Public participation

With the site being in the public eye, and bordering the Bergvine Primary School, there was a fair amount of interaction with the general public during the excavations. This included visits to the site by members of the SAPS, Department of Transport, local historians, and battlefield guides. The main interaction, however, was with staff members of the school and school children, who arrived in organised groups. A number of informal talks on site with reference to the finds, archaeology, heritage in general, and the Anglo-Boer War were presented to these school groups during the tim~ spent on site. From an educational point of view, this project made a fairly substantial contribution.

Conclusions and recommendations

The archaeological rescue excavation of the accidentally-discovered Anglo-Boer War site yielding ammunition and other cultural material was completed successfully. The material dates to the period of the Anglo-Boer War and the evidence points to the location of a blockhouse here, which formed part of a line of similar fortifications, erected in May 1901, along the Upper Tugela. A similar blockhousepreserved as a National Monument site and being used by the MOTHS - is located approximately 400m to the northeast near the SAPS Bergville offices.

In addition to nearly 6 000 unspent .303 rifle cartridges recovered, the site also produced fragments of contemporary ammunition cases, paper wrapping for the cartridges, sheets of the corrugated iron from the blockhouse, nails, screws, the 'shingle' used between the blockhouse sheets, liquor and carbonated beverage bottle fragments, and other metal objects. The location of the site on top of a ridge

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the following institutions and individuals for their assistance and support: The Department of Transport, Bergville, for recovering the material and reporting it to the SAPS and for allowing us to properly investigate the site, halting their work until work was completed; the SAPS Bergville (and especially Captain Piet van der Berg), who assisted with the recovery and storage of the material, as well as for contacting Amafa to investigate the discovery; Amafa, for providing the financial assistance and rescue permit in order to conduct the work, and especially Mr Derrick Mhlongo of Amafa for his help during the excavations; our two local assistants, Sifiso and Bricks, for all their hard work during the excavations.

Dedication

Finally, we would like to dedicate this article to Ken Gillings who recently passed away. It was his suggestion that we publish our results in this Journal.

REFERENCES

Aerial views of the site location and position of archaeological excavation: Google Earth 2012.

1 :50000 Topographic Map Series location of site: 2829CB Bergville.

Bester, R, Small Arms of the Anglo-Boer War 1899-1902: A comprehensive study of all rifles, carbines, handguns and edged weapons used by the opposing forces during this conflict.(Kraal Publishers, Bloemfontein, 2003).

Boyden, P B, Guy A J and Harding, M, The British Army in South Africa 1795-1914 (National Army Museum, Clifford Press Ltd, Coventry, UK, 1999).

Lastovica, E & Lastovica, A, Bottles and Bygones: A guide for South African collectors (Don Nelson, Cape Town, 1990).

Pakenham, T, Die Boere-Oorlog (Jonathan Ball Publishers, Johannesburg, 2009).

Pelser, A, 'Report on the archaeological rescue excavation of the Anglo-Boer War (1899-1902) Blockhouse in Bergville, Tugela District, KwaZulu-Natal', unpublished report APAC 012/05,2012.

Pietermaritzburg Archives Repository (NAB): Photograph, NAB, Reference C4978 and Photograph, NAB, Reference C4979

Van Vollenhoven, A C & Van der Walt, J, 'A historical archaeological rescue investigation into Anglo-Boer War ammunition, found at Ifafi, North-West Province', unpublished report, Archaetnos CC, AE1 03, 2001.

Return to Journal Index OR Society's Home page

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org