The South African

The South African

Published on the Website of the South African Military History Society in the interest of research into military history

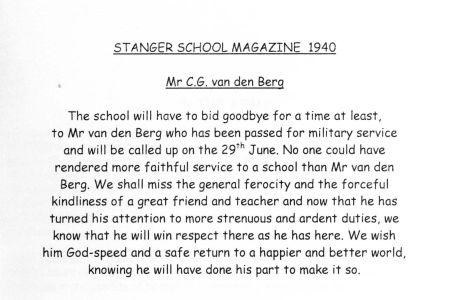

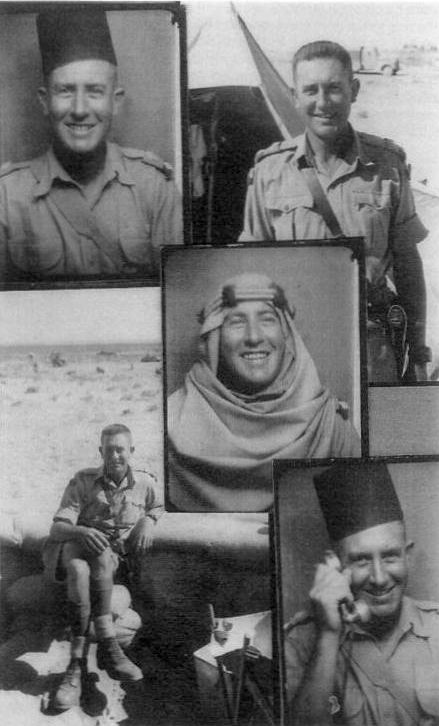

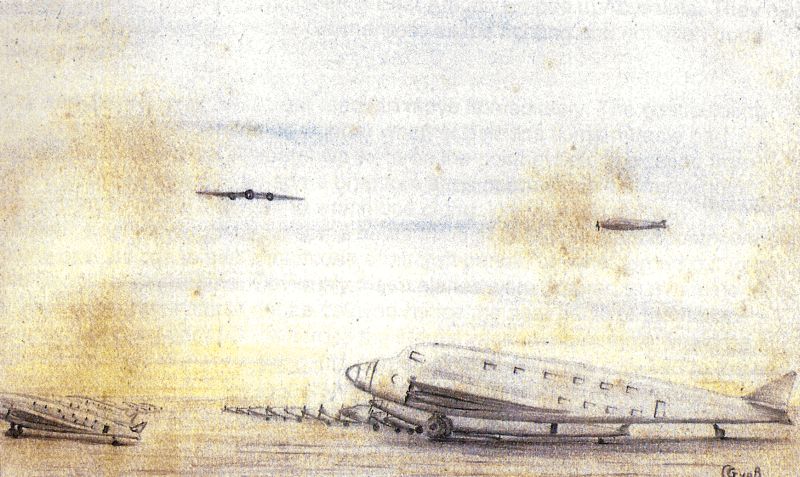

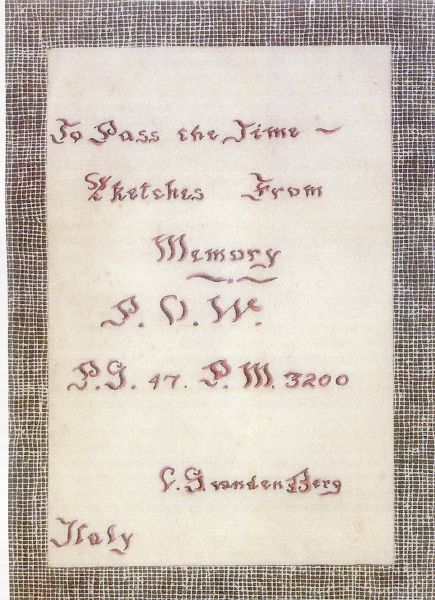

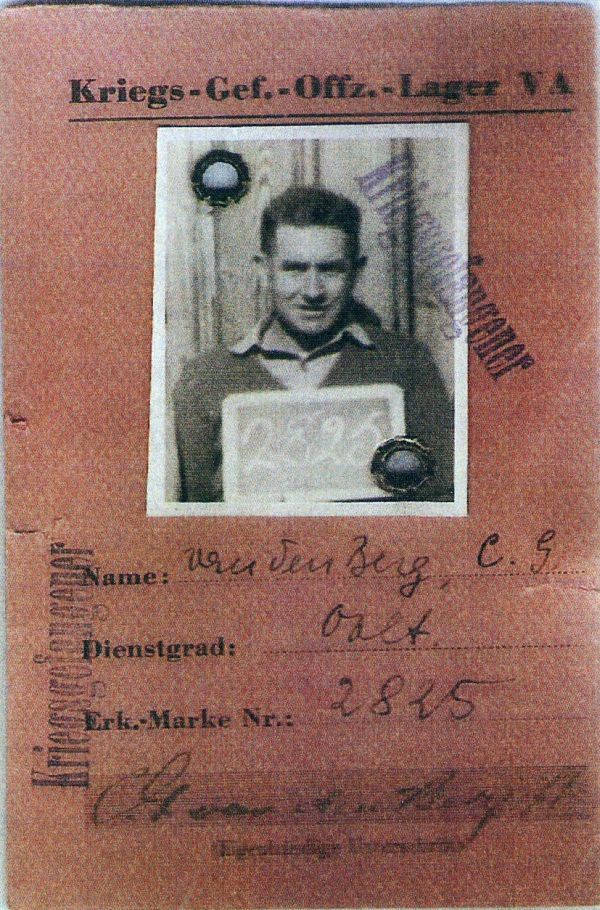

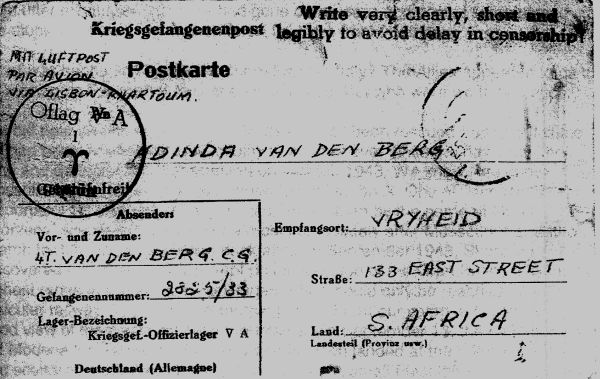

Lieutentant Coert Grobbelaar van den Berg 1939.

VIOLENCE, to an extent and of an intensity, unparalleled

in recorded history, ravaged the world during these years.

It resulted in devastation and destruction of incalculable proportions.

It brought death, swift or lingering, to fifty million men, women

and children and floods of tears of sorrow.

It left a gaping gash in man's body physical

and all but destroyed his soul.

Incidental quotations in this story, where the Sources are not mentioned, are taken from the text of The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich by William L. Shirer, or from extracts in this book taken from other Sources. I found the information in this book most valuable and have used much of it in this story. It is a book variously acclaimed as ... a magnificent work ... a book in which revelations stud the pages ... monumental ... a book fascinating and terrifying. It is well indexed and richly provided with references to the sources from which the author obtained his information. Other sources from which I obtained information, are mentioned in the body of the story.

Coert Grobbelaar van den Berg Pietermaritzburg 1973

I would have liked to mention the names of some of the men who shared these experiences. Then I decided to mention no names, rather than mention some of them.

Some of these men live unpretentious lives, making no claim to great importance. They pursue their occupations where no footlights cast their glare.

Others occupy some of the highest positions in the political, judicial, academic, industrial and commercial fields. The accumulation of years has forced some of them off-stage, leaving them to watch the world go by and pondering its future.

Others, alas, have answered the "sunset call".

In those far-off days these men established amongst themselves a bond of understanding and solidarity which sustained them during those dark days when the Allied forces were mostly on the defensive and, at times, suffering heavy losses. By the time the tide had turned in favour of the Allies, these men were prisoners of war. Then, too, this bond enabled them to face long periods of adversity of an entirely different nature.

"this bond enabled them to face long periods of adversity ... "

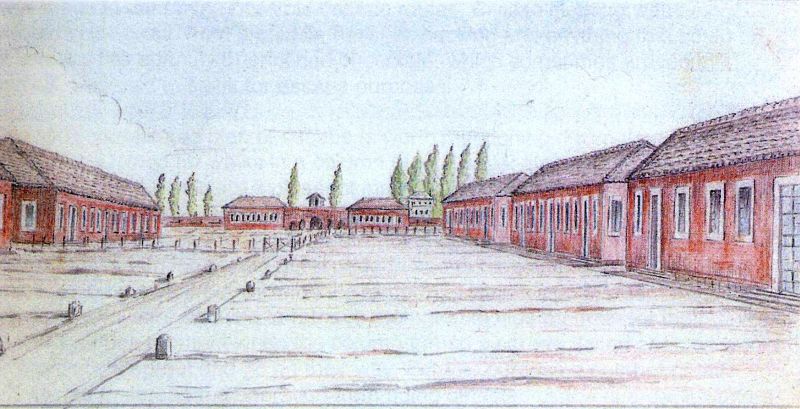

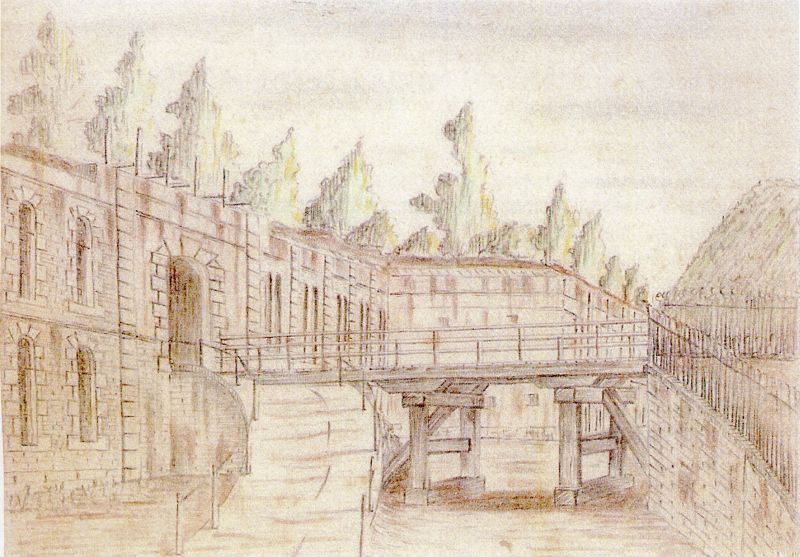

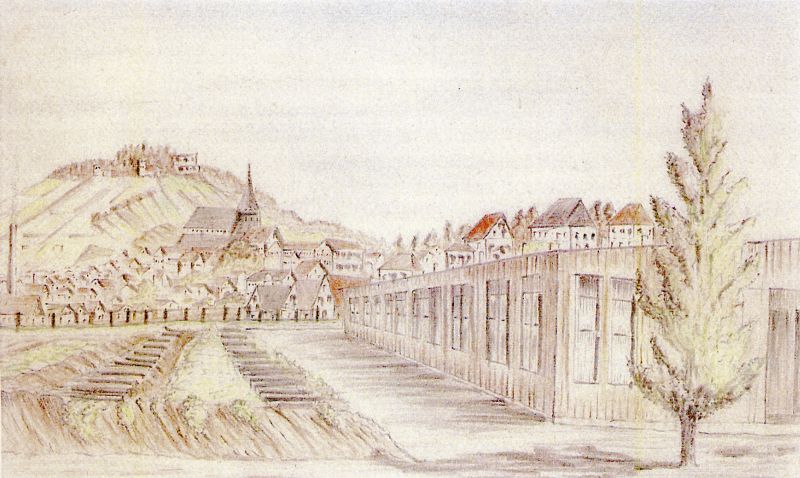

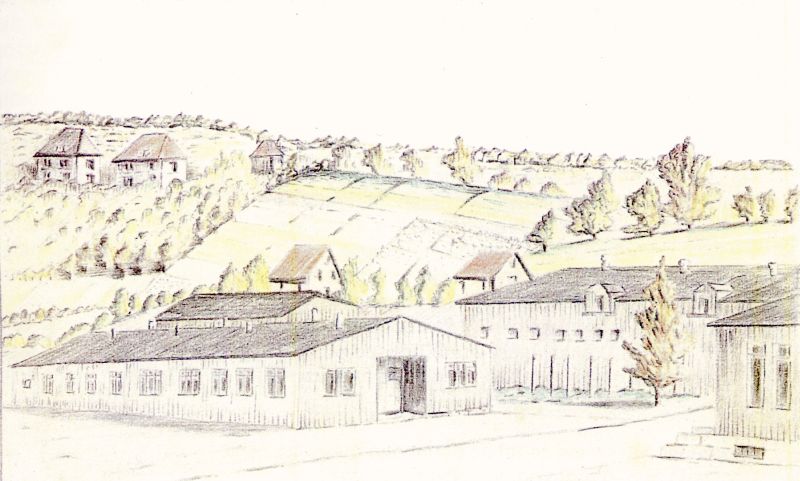

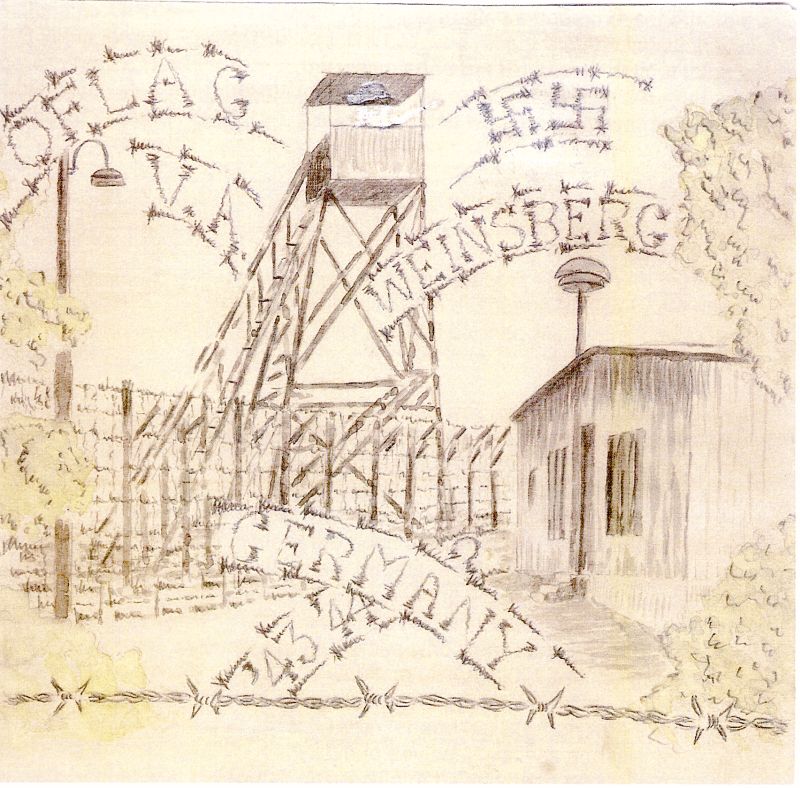

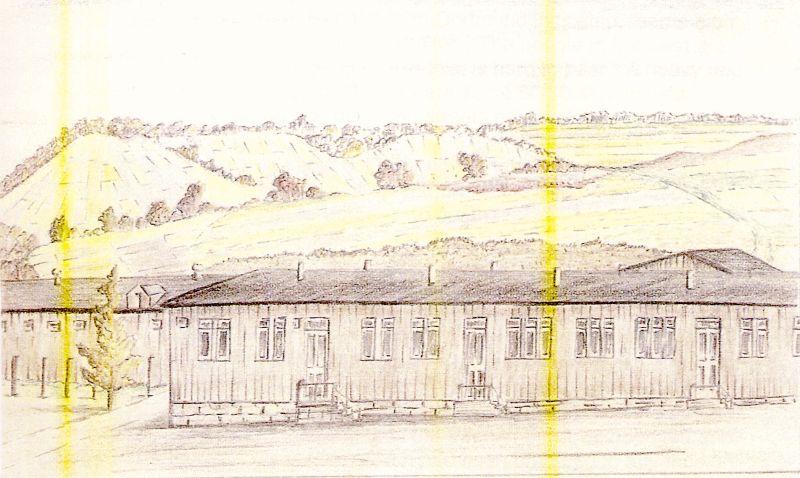

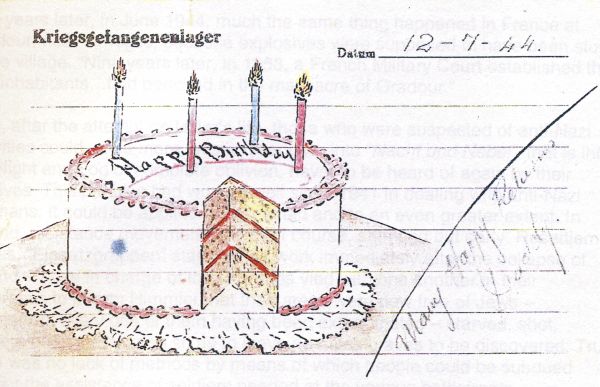

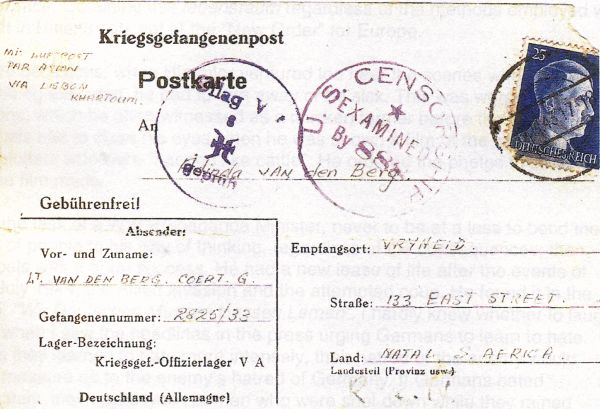

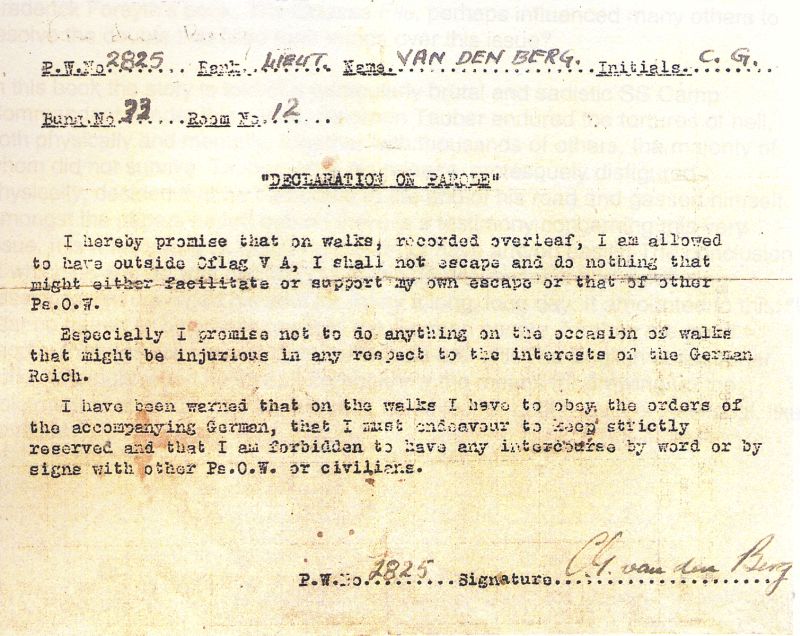

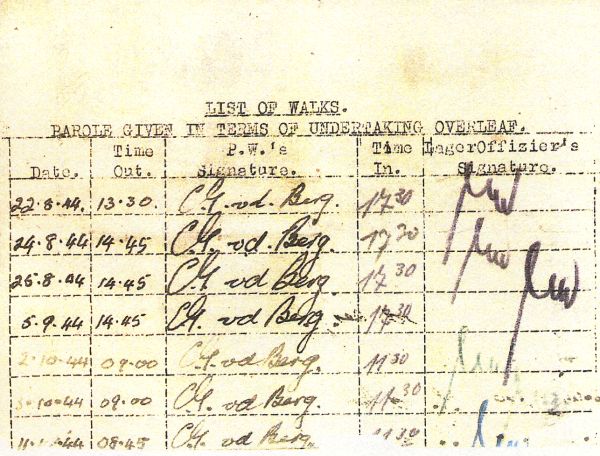

- prisoners of war - Weinsberg, Oflag V A, May 18, 1944

Down the years millions of soldiers have remained nameless in the annals of history. They were remembered for the short space of a lifetime by those who knew them. They asked for no further recognition. So let it be with these men.

CHAPTERS

In the year 1939, I entered into an agreement for better or worse; for richer for poorer. This was halfway through my lifespan to date when we are all encouraged to plant a tree in '73. Bachelorhood had been getting me down for some time. Now there came a woman in my life without whose constant companionship, I had firmly decided, life would be exceedingly empty.

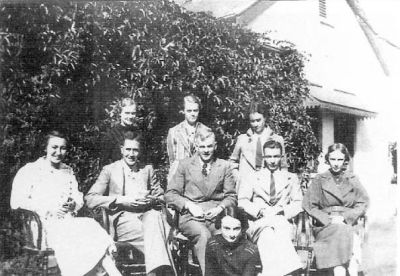

The staff of Stanger High School, 1939

A few years before there had been on the staff of the school where I was teaching, a young teacher. She was haughty, aloof and standoffish towards me and I let her be. Time went by until we found ourselves playing golf together. She was keen on hockey and so was I. We were both playing regularly in the local mixed hockey teams which reached quite a high standard. Not one of us could ever get a ball past this woman at fullback. This fact became known outside local circles and she was invited to take part in preliminary trials to select a Natal Women's Hockey side to tour Rhodesia. On several occasions I took her to these trials in my derelict motorcar. She was selected for the Natal side.

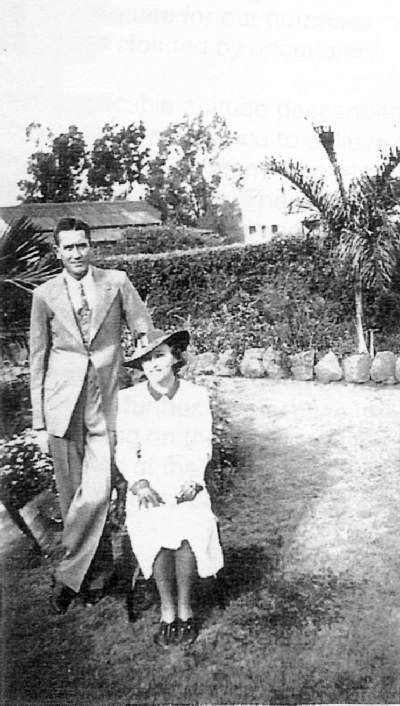

Catherine Daphne Hackland -

"she was haughty, aloof and standoffish"

By this time I had discovered that apart from the interest we shared in these, more or less, unimportant activities, there was much besides which could lead to a strong bond between us.

While she was away on this tour I suffered from emotional turbulence and mental dis-equilibrium. I did not hesitate to tell her about it when she came back. I asked her if she did not see plainly before her eyes the man she should consider marrying. Her response was such that I took it to mean that she did and that was it. Of the many pacts and alliances that are to be mentioned in this story, this is the only one, which still stands.

"Of the many pacts and alliances ...

this is the only one, which still stands."

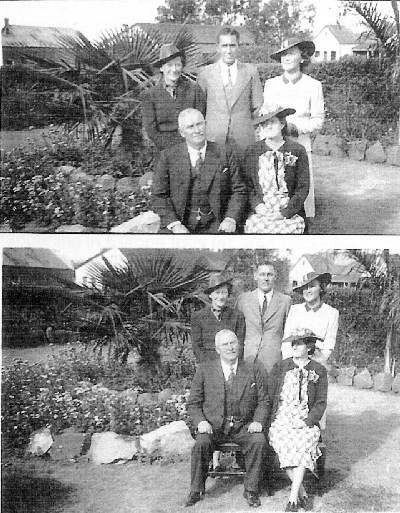

Wedding day, July 8, 1939

Why was it pre-destined that a corporal from World War I, Adolf Hitler, should cross the path of so many millions and why at this particular time in our lives? When we were married on July 8, 1939, minor flashes had already come from the dark war clouds, which had spread over parts of Europe. They were now spreading their ill-boding shadows wider and wider. The world was waiting for and dreading more flashes which were sure to emanate from them and to send their resultant roars, rumbling across the whole world.

On September 1, the igniting flash came. The roar reached Great Britain by September 3, and its rumblings were heard in South Africa on the 5th of that month. We were at war with the Rome-Berlin Axis powers. On the same day, the United States of America pretended that she had heard neither roar nor rumble.

She would wait for something more alarming before intervening. She declared her neutrality.

We had bought our furniture and fittings with all the care and interest, which this process inevitably engenders, in every young couple. We installed it all in a home quite adequate for our purposes. Yes, visions of comfortable home life in the offing but clouded by uncertainty.

An inexplicable attitude descended upon this land, which had just declared war. There was a reluctance to believe that a SECOND world war had started when there were still so many who remembered the FIRST one, the war which was to have ended all wars. There appeared to be a complete disregard of what had been happening in Europe for some years before we became involved. The events, which were to shake everybody into a full realisation of what the world was to experience, still lay hidden in the future. For the present the slogan was "business as usual". What had been happening in Europe thus far, had not come very close to us as it had not come close to many others. Perhaps what had happened, could have been avoided. Matters would soon settle down and develop no further. In any case, there were a million Allied troops ready to hang their washing on the Siegfried Line and France was secure behind the formidable fortifications of the Maginot Line. In Britain, this became known as a "phoney war". A picture to belie all this was soon to be painted.

At this stage we should take a close look at an extraordinary man on whom the eyes of the world were to become focussed for a long time.

Some years after World War I, Adolf Hitler had laid his soul bare to the world in Mein Kampf, the first volume of which he wrote in the fortress of Landsberg. The story of how he came to be in this fortress will be told in due course. For the present we are more concerned with some of the views of this man whose experiences in his early youth had such a profound effect on the history of the world.

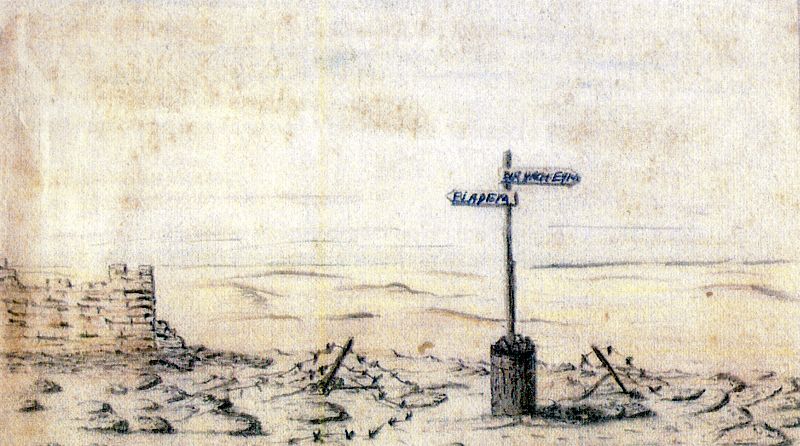

When I read Mein Kampf for the first time before the war, I must admit that it frightened me. To me it seemed inconceivable that this man did not mean what he said. Whatever one might have thought of the reasoning and arguments he employed to arrive at certain conclusions, these conclusions were stated with a conviction, which I could only regard as inflexibly firm. One had every reason to fear the consequences should he ever be placed in a position to translate words into action. At the beginning of 1944 when I was a prisoner of war in Germany, I read it again. A warrant officer (feldwebel) lent me his copy. He operated in the camp as some sort of liaison agent between the prisoners and the detaining power, our hosts. I wondered why he almost begged me to read it again. At that stage the signposts on the road along which Hitler was taking Germany showed clearly that he was not leading his people to the glorious future Mein Kampf had promised them. I had a feeling that this feldwebel had by then discarded any illusions he might have had. He was not a happy German. I read this book again recently when it was an historic document and no longer a blueprint of things to come.

Hitler's father, after much chopping and changing of jobs, was a custom's officer on the border between Germany and Austria. He died when Adolf was thirteen years old. He had often quarrelled with his son, as he wanted him to prepare himself to join the civil service. Adolf bluntly refused to listen to his father. At the realschule he neglected the subjects he disliked. As it happened, circumstances assisted him to escape being a civil servant. He was forced to leave school for a year because of a chest complaint and his mother was advised not to let him prepare for a career, which would necessitate his working in an office.

Upon his recovery he left the realschule to attend the academy where a different choice of subjects was offered. He was happy doing the things he liked. Then his mother died. "This", says Hitler, "put a brutal end to all my fine projects ... The allowance which came to me as an orphan was not enough for the bare necessities of life. Somehow or other I would have to earn my own bread ... With my clothes and linen packed in a valise and with an indomitable resolution in my heart I left for Vienna ... I was determined to become something but certainly not a civil servant."

He learned that he had failed to pass the entrance examination to the Academy of Arts, which he wrote shortly before his mother's death. He was told that the School of Architecture would be a better approach for him. His abilities lay more in that direction.

"I was forced," Hitler writes, "bitterly to rue my former conduct in neglecting and despising certain subjects in the realschule. Before taking up Courses at the School of Architecture in the Academy, it was necessary to attend the Technical Building School; but a necessary qualification for entrance into this school was a leaving certificate from the middle school and this I simply did not have."

He had to spend five years in Vienna. "Five years", he says, "in which, first as a casual labourer and then as a painter of little trifles, I had to earn my daily bread." Hunger, misery and deprivation were his constant companions during these years. The manual labourers in Vienna like himself, "lived in surroundings of appalling misery ... I shudder even today when I think of the woeful dens in which people dwelt, the night shelters and all the tenebrous spectacles of ordure, loathsome filth and wickedness."

He tried desperately to understand the conditions around him. He deprived himself of many of the necessities of life in order to buy books dealing with attempts that had been made and were being made to shape the political, economic and social affairs of people and nations. He loathed Hapsburg Austria. "It was an empire," he says, "which had a population of 52 million with all the perilous charm of a state made up of multiple nationalities." Above all there were ten million Germans who were denied the opportunity of joining their Fatherland. The "gigantic city of Vienna", seemed to him to be "the incarnation of mongrel depravity". About his reading habits, he says, "From early youth I endeavoured to read books in the right way and I was fortunate in having a good memory and intelligence to assist me." It is quite clear that he read widely but one-sidedly.

"Vienna", he writes, "was a hard school for me but it taught me the most profound lessons of my life. I was scarcely more that a boy when I came to live there and when I left it, I had grown to be a man of a grave and pensive nature ... in Vienna, I developed a faculty for analysing political questions in particular. A weltanschauung and a definite outlook on the world took shape in my mind. These became the granite basis of my conduct at the time. Since then I have extended that foundation only very little and I have changed nothing in it."

Furthermore, "during that period my eyes were opened to two perils, the names of which I scarcely knew hitherto and had no notion whatsoever of their terrible significance for the existence of the German people. These two were Marxism and Judaism."

Having made this discovery there was hardly a term of abuse, which he did not hurl at the Jews.

Everything that he saw around him was dominated and manipulated by these "vermin ... rabble ... pests ... liars ... murderers". All forms of government, all political parties, all state and private enterprises, all institutions, including schools and other places of learning, all labour organisations and trade unions, all news media and propaganda were in their hands. He despised the "idiots" and "imbeciles" more particularly amongst those who claimed to be German, who allowed themselves to be used as tools to do the destructive work of the Jews because they were too obtuse and stupid to realise wnat despicable roles they were being made to play.

In the fortress of Landsberg he also had time to reflect on his two happier years in Munich where he stayed after he left Vienna. He was at Munich at the outbreak of Warld War I in 1914. This event pleased him so much that he fell on his knees in gratitude because a war was necessary before Germans would be able to occupy their rightful place in the sun. He joined the army and spent four years on the Western Front. As a dispatch rider he was awarded both the second and first class Iron Crosses. He was wounded in the early stages of the war but returned to the Front as soon as possible. Towards the end of the war he nearly lost his eyesight as a result of a gas attack in the trenches. He was recovering in a military hospital when the news of the collapse of Germany in 1918, was announced. Hitler wept bitterly. He could not believe that all the sacrifices of the German soldiers have been in vain.

"Although the misfortunes of the Fatherland," Hitler remarks, "may have stimulated thousands and thousands to ponder over the inner causes of the collapse, that could not lead to such a thorough knowledge and deep insight as a man may develop who has fought a hard struggle for many years so that he might be master of his own fate." Here in the Fortress he could now draw on his past experiences his observations, and his faculty for analysing political questions, his thorough knowledge and deep insight; his definite outlook on the world to provide all the answers for the collapse of Germany and to indicate the road that had to be followed in the future.

Jews manipulated the strikes and revolutions in 1918, preventing the Germans from gaining the victory, which was in sight. They stabbed Germany in the back. They imposed the Treaty of Versailles on Germany. They thrust the hated democratic parliamentary concoction, the Weimar Republican Constitution on Germany. They favoured the contamination of Aryan by non-Aryan blood which "the hereditary sin in this world and it brings disaster to every nation that commits it".

He was to keep up this vituperation against the Jews all through his life until a few hours before his death when he gave his last piece of advice to his successors - who fortunately never succeeded him - in these words: "Above all, I enjoin the government and the people to uphold the racial laws to the limit and to mercilessly resist the poisons of all nations, international Jewry."

"There is only one answer', he writes in Mein Kampf, "A revolutionary conception of the world and human existence." This revolutionary movement will achieve decisive success when the new weltanschauung has been taught to a whole peopIe or subsequently forced upon them, if necessary, and when the central organisation, the movement itself is in the hands of those few men who are absolutely indispensable to form the nerve-centre of the coming state. "

What had been neglected to be done about the Treaty of Versailles was to be done now. "Each point of that treaty," Hitler asserts, "could have been engraved on the hearts and minds of the German people and burned into them until 60 million men and women would find their souls aflame with a feeling of rage and shame, and a torrent of fire would burst forth as from a furnace and one common will would be forged from it like a sword of steel. Then the people would join in a common cry: To arms again."

It is a little difficult to trace the processes of heat transmission in this fiery, molten metaphor and this kind of language which might have induced some people to believe in hot air and vapourings only, coming from this man. The message, nevertheless comes over loud and clear: To hell with the Treaty of Versailles.

"The right to territory", says Hitler, "may become a duty when a great nation seems destined to go under unless its territory is extended. And this is particularly true when the nation in question ... is the German mother of all the life which has given shape to the modern world." Lebensraum for the German people can only be obtained when "the portion which has more or less retained its sovereign independence can resort to the use of force for the purpose of reconquering those territories which had once belonged to the common Fatherland."

As for the antagonistic press, "the scream of the 12-inch shrapnel is more penetrating than the hiss from a thousand Jewish newspaper vipers". Truly there was much to be done according to Hitler, for "think of those hundreds of thousands who set out with their hearts full of faith in their Fatherland that never returned; ought not their graves to open so that the spirits of those heroes, bespattered with mud and blood would come home and take vengeance on those who had so despicably betrayed the greatest sacrifice which a human being can make for his country? Then "for a thousand years to come, nobody will dare speak of heroism without recalling the German Army of the World War. And then from the dim past will emerge the immortal vision of those solid ranks of steel helmets that never flinched and never faltered."

After the war Hitler could not, like thousands of others, make up his mind what to undertake. In 1920 he was finally demobilised and he decided to go into politics. With non-existent means at their disposal, a small group of members of the German Workers' Party met every Wednesday in one of the cafes of Munich. They arranged small public meetings but few attended. Hitler had joined this Party as its seventh member. At the beginning of 1920, he put forward the idea of holding their first mass meeting. His suggestions were opposed. The other members advised caution. This was not a word, which fitted easily into Hitler's vocabulary. Their advice infuriated him. He himself undertook to make all the arrangements and to do the necessary publicising. The meeting was held on February 24, 1920 in the chief hall of the Hofbrau Haus on the Platz in Munich.

At the appointed time, Hitler mentions in Mein Kampf, "the great hall was packed to overflowing". Hitler started to speak "amidst a hailstorm of interruptions". He went on. "After half-an-hour the applause began to drown the interruptions." Hitler was explaining the 25 theses, which constituted the programme of the new party. To the name German Workers' Party, had been prefixed the words National Socialist. The National Socialist German Workers' Party, commonly known as the Nazi Party was launched at this first mass meeting. (The word "Nazi" is derived from the German pronunciation of the first two syllables in the word "Nationaaf', approximating "Nahtzi".) Hitler reports, "When the last point was reached, I had a hall full of people before me, united by a new conviction, a new faith and a new will ... I knew that a movement was now set afoot among the German people which would never pass into oblivion."

The success of this meeting was of the utmost importance in shaping Hitler's approaches to the masses, which he succeeded so undeniably to influence. He had proved to himself for the first time that he had the ability to capture and hold the attention of a large audience and even to sway opponents to his way of thinking. He exploited his undoubted ability in this direction by addressing numerous meetings. "Such audiences," he writes, "brought me the advantage that I slowly became a platform orator at mass meetings and gave me practice in the pathos and gesture required in large halls that held thousands of people." On some such occasions he even managed to persuade his audiences that the Treaty of Brest Litovsk, which the Germans imposed on Russia on March 3, 1918, towards the end of World War I, was a mild one in comparison with the Treaty of Versailles. Only a Hitler could justify Russia being deprived, according to Shirer, of "56 000 000 inhabitants, or 32% of her whole population; a third of her railway mileage, 73% of her total iron ore, 89% of her total coal production; and more than 5 000 factories and industrial plants. Moreover, Russia was obliged to pay Germany an indemnity of six billion marks."

His audiences began to see in Hitler the courageous and fearless fighter for German existence. Did his Programme of Principles not emphasise that common welfare and gain would be placed before individual welfare and gain - the catch phrase, Gemeinnutz vor Eigennutz?

It is one thing for a people secure, or even reasonably secure, in their way of life to reject the voice of a revolutionary; it is another thing for a people who consider themselves woefully deprived of hope for the future to reject such a voice. The people of Germany found themselves in a trough of despondency. It was a period of low ebb and depression all round. There were in the region of six million unemployed Germans and even amongst those who were employed there was discontent and visions of a dismal future. It was in Adolf Hitler's revolutionary approach that the people began to see their salvation. They needed someone who spoke as forcibly and with such obvious conviction about righting the wrongs, which Germany had suffered and continued to suffer.

At his meetings Hitler welcomed opponents but they were not to prevent him from putting his message across. His Storm Troops - Sturmabteilungen (SA) - were always there to deal violently with elements that tried to break up his meetings. These Storm Troops were but the first of the organisations, which he created to assist him in dealing ruthlessly with opponents. They wore brown shirts and were recognised by their swastika badges.

He later formed his Protection Units - Schutzstaffel (SS). These men received more specialised training that the SA, who were merely required to be brawny and tough for their particular tasks. The SS wore black tunics. The initials SS lent themselves to being reproduced in print and on the lapels of uniforms in the form of two flashes of lightning.This symbolised the lightning attention, the lightning obedience, the lightning action demanded of these troops. During the war their battle dress changed colour to a dark green but the characteristic symbol remained on their lapels.

The Secret State Police - Geheime Staatspolizei (Gestapo) - had to beformed to uncover any intrigue, which might be brewing against Hitler. "It was at first", says Shirer, "little more than a personal instrument of terror employed by Hermann Goering to arrest and murder opponents of the regime. It was only in April 1934 ... that the Gestapo began to expand as an arm of the SS." Heinrich Himmler was in charge. With the assistance of Reinhard Heydrich who was head of the Security Branch of the SS - Sicherheitsdienst (SD) - the trio SS, Gestapo, SD was to become a "scourge with power of life and death over every German",

The Party, which Hitler had joined in 1920, chose him as its Chairman in August 1921. In place of decision by majority vote of the committee, the principle of absolute responsibility of the Chairman was adopted. He had insisted on that. Rarely from that day onwards did he flinch from taking decisions for which he assumed full responsibility.

"The art of leadership," wrote Hitler, "as displayed by really great popular leaders in all ages consists in consolidating the attention of the people against a single adversary ... The more the militant energies of the people are directed toward one objective the more will new recruits join the movement, attracted by the magnetism of its unified action and thus the striking power will be all the more enhanced. The leader of genius must have the ability to make different opponents appear as if they belonged to one category ... The single adversary was always that bacillus which is the solvent of human society, the Jew ... here, there and everywhere."

Hitler fully appreciated the value of flags, banners, badges and insignia to create colour, atmosphere and solidarity at mass meetings. These were at times attended by over a hundred thousand cheering supporters. These were the occasions, which stimulated Hitler to reach heights of oratory, which stirred the Germans to a frenzied display of emotions almost foreign to their nature. In addition, the power of the radio brought his speeches and the sounds of cheering multitudes to millions of others. One can well understand Hitler's belief in, the power of the spoken word and his jubilation when he first discovered that he was a master at using it. Perhaps it is true to say that Hitler might have failed to become Der Führer but for this gift, which gave him such a tremendous advantage over his political rivals. He could blow on smouldering patriotic cinders like no one else could until they glowed red-hot and burst into devouring flames.

About the Nazi flag which usually hung in profusion from all vantage points at mass meetings, he had this to say: "It incorporated those revered colours expressive of our homage to the glorious past which once brought so much honour to the German nation; but this symbol was also an eloquent expression of the will behind the movement. We National Socialists regarded our flag as being the embodiment of our Party Programme: the red expressed the social thought underlying the movement; white, the national thought and the swastika signified the mission allotted to us - the struggle for the victory of Aryan mankind and at the same time the triumph of the ideal of creative work which is in itself and always will be anti-Semitic."

There can be no doubt about it that Hitler had himself in mind when he wrote: ... "When the abilities of theorist and leader and organiser are united in the one person then we have the rarest phenomenon on this earth."

Many people have tried to evaluate this man's character and makeup. Robert Ardrey, in his book The Social Contract, to which I shall return at a later stage, describes Hitler as an example of what is encountered throughout the animal kingdom, more especially amongst primates. He is an example in man of an undoubted alpha, just like Winston Churchill, "the dazzling gift to wartime Britain", is another example of an undoubted alpha. "The omega" he says, "commands the attention of only his or her inmates. The true alpha holds the attention of the entire group and through giant magnetism accomplishes as a normal event what would otherwise be a miracle." Although Ardrey describes the alpha in these terms, he makes no attempt to explain the alpha-phenomenon. He says, "We may recognise him, follow him, applaud him, put him to the most useful of purposes. But while many have attempted to describe him, few have been the observers brash enough to explain him." He continues, "So many variables enter the determination of alpha-ness that one faces an equation beyond solution. Strength, intelligence, maleness, courage, health, indefinable persistence, ambition, confidence - all are involved ... luck probably of high significance. But the most remarkable quality ... is political acumen."

We will never know how many Germans would have chosen from time to time to call a halt to Hitler's dark ambitions. He built up an organisation so powerfully ruthless towards his opponents who may have had alpha-ambitions and he showed so much concern for true Germans who bowed to him and who hailed him as their alpha that it will perhaps remain forever that inexplicable phenomenon of followers being irresistibly drawn by a giant magnetism.

During the two years while Hitler was Chairman of the new Party, from August 1921 to November 1923, the Party had grown considerably and Hitler was full of confidence. In November of the year 1923 he staged what was to become known as the Beer Hall Putsch. It failed and as a result he was held captive and on February 28 of the following year, the People's Court in Munich sentenced him to five years imprisonment. He only served about eight months and was then released. He was imprisoned in the fortress of Landsberg where he had time to reflect on his experiences and to write the first volume of 'Mein Kampf. There was at the time when the Putsch was attempted, a movement afoot in Bavaria to secede from the German Republic. Hitler, of course had no respect for the Weimar Republican Democracy that had been imposed on Germany but any attempt to dismember Germany still further after the war was more than Hitler could tolerate. He also saw an opportunity for a shortcut to greater power than he had had, if he could gain control over this part of Germany. He had been trying to persuade the three key men in Bavaria to assist him in resisting such a move. They were Gustav von Kahr, the State Commissioner, General Otto von Lossow, Commander of the Reichwehr - the army in Bavaria, and Colonel Hans von Seisser, the Head of the State Police. They were decidedly uncooperative. Hitler was a nonentity and an upstart.

Some businessmen in Munich had quite innocemly arranged for a meeting to be held in the Burgerbraukeller, a large beer hall to discuss business matters. Hitler received news that Kahr, Lossow and Seisser were to attend this meeting. He suspected that Kahr would make use of this opportunity to announce the secession. He decided that the SA would surround the hall and he would take over the meeting.

While Kahr was speaking that night, Hitler entered the hall and dramatically fired a shot at the ceiling. He told them that the hall was surrounded by SA troops. No one was to leave the hall and unless they were quiet a machine gun would be used on them. He informed his audience that reinforcements were marching to the hall and that the Bavarian army and the police were on his side. There was, of course, not a shred of truth in this concocted story.

He ordered the trio, Kahr, Lossow and Seisser to accompany him to a small room off the stage. There he parleyed with the three men but he found them most obstinate. He had to adopt other methods. He locked them in and entered the main hall. He told the audience that the three leaders had agreed to his forming a new government and that General Erich Ludendorff of Western and Eastern Front fame would command the new national army to be formed. The three men heard loud applause in the hall and wondered what it was all about.

Hitler had arranged for Ludendorff to be brought into the hall at this dramatic moment. Ludendorff did not really know what was happening but he was also opposed to the secession move. He would cooperate. Hitler asked Ludendorff to speak to the three locked-up men and confirm what he had just told the audience. Ludendorff succeeded to the point of making the three men believe the story. They agreed to each one of them making a short statement in the hall confirming what Hitler had said.

This having been accomplished the people were allowed to leave the hall. Hitler had another engagement and left Ludendorff with the three men to arrange the take-over to which they had agreed. They, however, made excuses that they had urgent matters that needed attention first. A meeting could be arranged later to suit Ludendorff's convenience. When Hitler returned to the hall only Ludendorff was there.

In the meantime, the SA under Ernst Roehm's command had occupied the War Ministry building. As soon as Kahr left the hall, he recovered from the stunning blow that Hitler had dealt him. He issued notices that their statements had been forced from them at pistol point. They were meaningless. He alerted the army and the police.

Hitler's plan had backfired and he was not at all sure what to do. Ludendorff advised him that they should stage a demonstration march to the War Ministry the following morning with a view to negotiations. Roehm and his SA were now encircled by the Bavarian army. Ludendorff was sure that the ex-soldiers would, out of consideration for him, not interfere with the march. Hitler agreed reluctantly. He had always disliked following other people's advice but he had no alternative plan.

The next morning the march started with Ludendorff, Hitler and Goering heading the column, with Hess close by. When they were about to enter the square in front of the War Ministry, a police detachment blocked their way. Shouts came to let them proceed as Ludendorff was amongst them. These policemen were not ex-soldiers and the name Ludendorff struck no chord. A shot rang out and the police opened fire. Sixteen of Hitler's followers were killed instantly. Later, two more died of wounds. Hitler fell and dislocated his shoulder. The others fled in confusion. Ludendorff alone kept marching to the War Ministry where he was arrested. Hitler and some of his followers were rounded up and imprisoned until the trial in February 1924. Goering and Hess had managed to escape over the border, Roehm was also arrested.

The trial lasted for 24 days. The proceedings were reported by journalists far and wide. Hitler defended himself so vigorously and so tellingly that he enhanced his image amongst his followers and certainly caused his sentence to be much lighter than could have been expected. Hitler was sentenced to imprisonment for five years. He served less than a year and was released.

The Central Authorities in Berlin, no doubt, saw no great crime in Hitler's attempt to stop secession. Shirer remarks: "Hitler had transformed defeat into triumph ... impressed the German people with his eloquence and the fervour of his nationalism and emblazoned his name on the front pages of the world." Ludendorff was acquitted at the trial.

Every year on November 8, the Beer Hall Putsch was commemorated in Munich and Hitler was there to pay tribute to the eighteen martyrs who died to further the Party cause.

The Volkischer Beobachter that the Party had acquired earlier as their mouthpiece had stopped appearing after Hitler was arrested. On February 26, 1925 it reappeared carrying an editorial by Hitler announcing "A New Beginning".

Hitler devoted quite a few pages in Mein Kampf to explaining why nobody should take on the leadership of a party before his thirtieth year. He was now 36 years old and considered himself more than ripe for leadership. He started to gather up the reins of the Party that had almost become defunct during his absence .. Hitler learned important lessons from the Beer Hall Putsch. He was later to admit that it was an amateurish attempt in the extreme. He should not have allowed Ludendorff to deal with those three men. He should have dealt with them in his own way. Moreover, it placed him in a position where he had to act on Ludendorff's advice. Never again would he allow control to slip out of his hands in this way. Never again would he allow a situation to develop in which he would be forced to accept advice from others. But it was a blessing in disguise. he thought. If the Putsch had succeeded, success would have been of short duration because the Party would at that stage not have survived the onslaughts against it. It had not been adequately established. He also realised that he would not get control by acting against the army. He would have to get their cooperation in future, at least until he was firmly entrenched in power.

Largely because of his experiences in the abortive Beer Hall Putsch, Hitler had decided to make use of the channels provided by the democracy of the Weimar Republican Constitution. He would build up his party until it could command a majority vote in the Reichstag. Then he would smash the whole system from within. It took him longer than he expected but along this path he gained valuable experience in political manoeuvrings in which he would eventually out-bid all his political opponents.

By 1932 his Party was still very much in the doldrums but none of the numerous other parties in Germany could obtain an over-all majority either. The result was that President Hindenburg had to request various leaders from time to time to try by means of coalitions and agreements with other parties to form some sort of stable government. No one achieved much success.

"As the strife-ridden year of 1932 approached its end," Shirer writes, "Berlin was full of cabals and of cabals within cabals ... Soon the webs of intrigue became so enmeshed that by the New Year 1933, none of the cabalists was sure who was double-crossing whom."

Amidst this confusion, Hindenburg eventually called on Hitler on January 30, 1933, to become Chancellor. Frans von Papen was Vice chancellor and eight of the eleven Cabinet posts were filled by conservative Nationalists from amongst Papen's followers. They thought they had "lassoed the Nazis to their own end". He, on the other hand, knew their weaknesses as well as he knew the weaknesses of his other political opponents and of the existing institutions and organisations that had nearly all ground to a halt owing to the ineptitude or unwillingness of the German people to make the Democratic Weimar Republic function adequately.

Hitler wasted no time in his position of Chancellor to out-do his opponents. The Nazi party in coalition with Papen's Nationalists had 247 seats out of the 583 in the Reichstag thus still lacking an over-all majority. Hitler paid no attention to Papen's suggestion that they should collaborate with yet another party to obtain the required majority. He had no wish to compromlse with other malcontents. He was not going to take advice. He had something far more favourable in mind for his Party. He would impress the President with his pleas to dissolve the Reichstag and to hold another election. The existing situation offered no solution. He was sure another election would lead to greater stability. He knew, he would then unlike in 1932 have the resources of the state at his disposal to fight the election. Hindenburg agreed. He was weary of it all and weak with age. The date for the election was fixed for March 5, 1933. The election campaign was on.

Very conveniently, the Reichstag fire broke out on February 27. Nothing could have given a better start to the Nazi campaign. It provided all the ammunltlon necessary to fire at the Communists who were accused of this devilish plot.

There appears to be little doubt today that leading Nazis had master-minded the whole incident but remained so far in the background that all accusations could only rest on conjecture: but it served their purpose to the hilt. The day after the fire had broken out, Hitler was ready with his plan. He persuaded the President to sign a decree "for the Protection of the People and the State". This decree suspended the "seven sections of the constitution which guaranteed individual and civil liberties". Germany was soon to learn what terrible power this innocent-sounding decree had placed in the hands of Hitler. The SA went on the rampage, not only against the Communists but also against everyone suspected of anti-Nazi activities. After all it was officially decreed that they could lay no claim to civil or individual liberties. Fear gripped the people. What was to happen to them should they dare not to vote Nazi? Was there any guarantee of a secret ballot?

On March 5, 44% of the electorate voted for the Nazi Party - a greater percentage by far than for any other single party. Hitler had 288 members in the Reichstag. With the support of 52 Nationalists from Papen's party, he commanded an overall majority of 16. This was most unsatisfactory. It fell far short of a two-thirds majority. Hitler had decided that he was going to establish his dictatorship by consent of parliament, and then there would be no comeback, no Beer Hall fiasco. He needed a two-thirds majority for this.

The next step was already clear in Hitler's mind. He had a draft bill all ready to present to the Reichstag at its first meeting. If passed, it would become the "Law for Removing the Distress of People and Reich". What could be more innocent sounding?

But first, the ceremonial opening of the Reichstag had to take place. The Reichstag building had been burned down and Paul Joseph Goebbels and Hitler had arranged for this ceremony to take place in the Garrison Church at Potsdam, a place hallowed by memories of the "old greatness" of Germany. The amount of humility that Hitler displayed on that memorable day towards the old President was to pay handsome dividends. There, in the presence of a splendid array of uniformed field marshals, generals, admirals and Junker highbrows, Hitler "stepped down, bowed low to Hindenburg and gripped his hand. There in the flashing lights of camera bulbs and amid the clicking of film cameras which Goebbels had placed along with microphones at strategic spots, was recorded for the nation and the world to see and to hear described the solemn handclasp of the German Field Marshal and the Austrian Corporal". Hitler assured the President that the "union between the symbols of the old greatness and the new strength has been celebrated. We pay you our homage".

And the result? Two days later Hitler's bill became law. The so-called Enabling Act was passed by a vast majority. The Social Democrats voted against it. They alone, as a Party had remained disenchanted by the superb actor at the ceremonial opening of the Reichstag. Their leader, Otto Wells told the Reichstag, "We German Social Democrats pledge ourselves solemnly in this historic hour to the principles of humanity and justice ... No Enabling Act can give you the power to destroy ideas which are eternal and indestructible". Hitler jumped up and shouted: "You come late, but yet you come: you are no longer needed ... The star of Germany will rise and yours will sink. Your death knell has sounded ... I do not want your votes. Germany will be free, but not through you!".

The house burst into "the Horst Wessel song, which would soon take its place alongside 'Deutschland uber Alles' as one of the two national anthems:

This Enabling Act meant in short, that the Reichstag was prepared to allow the Cabinet to rule the country for a period of four years without interference from the elected members. It was as if "they had voted themselves a four-year holiday". It was the Cabinet's responsibility to run the affairs of Germany. It gave Hitler a free hand in domestic and foreign affairs. He soon demolished the federal parliaments and established the complete unification of Germany much more effectively than he could possibly have done by means of his amateurish attempt ten years before. Papen was still vice chancellor but his power was nought for Hitler filled his Cabinet with his own loyal and fanatic supporters.

On July 14, 1933 a law was passed which stated: "The National Socialist German Workers' Party constitutes the only political party in Germany".

The outcome of the March election still rankled in Hitler's mind. Only 44% of the electorate had supported him. He would now do something which would have such a popular appeal that the whole nation would rally round him. The hated Treaty of Versailles would provide the excuse for taking his first step into the field of foreign affairs.

On October 14, 1933 Hitler announced Germany's withdrawal from the Disarmament Conference and the League of Nations because Germany was denied equality of rights by the other powers in that league. He decided that he would let the people say what they thought of the action. A plebiscite was to be held on November 12, in conjunction with an election for the new one-party state.

On the eve of the election, on November 11, the anniversary date of the 1918 Armistice, the "venerable Hindenburg" said in a broadcast to the nation: "Show tomorrow your firm national unity and your solidarity with the government. Support with me the Reich Chancellor and the principle of equal rights and of peace with honour and show the world that we have recovered and with the help of God will maintain German unity".

And the result? Some 96% of the registered voters cast their votes and 95% of these approved Germany's withdrawal from Geneva. The vote for the singleparty state was 92%. Even if one granted that fear of not voting, or of voting the wrong way, might have influenced the electorate appreciably, the people, nevertheless, gave Hitler the support for which he was angling - a resounding victory.

And so the year 1933 sped to its end. Shirer gives this brief account of the events of this remarkable year: "Hitler could look back on a year of achievement, unparalleled in German history. Within twelve months he had overthrown the Weimar Republic, substituted his personal dictatorship for its democracy, destroyed all the political parties but his own, smashed the state governments and their parliaments and unified and de-federalised the Reich, wiped out the labour unions, stamped out democratic associations of any kind, driven the Jews out of public and professional life, abolished freedom of speech and of the press, stifled the independence of the courts and coordinated under Nazi rule the political, economic, cultural and social life of an ancient and cultivated people. For all these accomplishments and for his resolute action in foreign affairs which took Germany out of the concert of nations at Geneva, and proclaimed German insistence on being treated as an equal among the great powers, he was backed, as the autumn plebiscite and election had shown, by the overwhelming majority of the German people."

Despite his successes, the year 1934 was to prove far from plain sailing for Hitler. Ernst Roehm had stood by Hitler since the early days when his brownshirted Storm Troops ensured that Hitler's meetings would not be broken up. By the year 1934 his "rough and ready" followers had increased in number to two and a half million. Roehm had lately been worrying and annoying Hitler with requests that the SA should be given a far higher status in Germany than hitherto. They should actually perform the functions of the Wehrmacht. Hitler was emphatic that his requests were utter nonsense. He would never agree to undermine the Wehrmacht and its powerful officer-corps until much more had been accomplished with their cooperation.

Hitler, nevertheless, on New Year's Day, 1934, appointed Roehm to his Cabinet and wrote to him: "I feel compelled to thank you ... for the imperishable services which you have rendered to the National Socialist movement and the German people and to assure you how very grateful I am that I am able to call such men as you my friends and fellow combatants". Still, this did not mean that Hitler had climbed down. He had reason not to climb down. Roehm was persistent in his demands despite, or because of, Hitler's friendly letter. In February he presented a memorandum to the Cabinet in which he proposed the same nonsensical arrangements implying that he should be Minister of Defence. When the contents of this memorandum became known it had the exact effect which Hitler knew it would have. It caused an outcry in the Wehrmacht. "No more revolting idea could be imagined by the officer-corps. Its senior members not only rejected the proposal but also appealed to Hindenburg to support them. The whole tradition of the military caste would be destroyed if the rough-neck Roehm and his brawling brownshirts should get control of the army." Hitler was in complete agreement. How could anybody be so stupid? Hindenburg was in his eighty-seventh year and the question of his successor had not been settled. Rumours were already rife that the officer class was bringing pressure to bear on Hindenburg for the restoration of the Hohenzollerns in Germany after his death. Hitler had made a good impression on the military caste and on the President at the ceremonial opening of the Reichstag. He could not afford to have the image of collaboration with the army and the navy, which he had established, destroyed by Roehm. He was therefore quick to assure the army and navy chiefs that nothing would come of Roehm's proposals. It was quite clear that Roehm's days were numbered. "After fourteen stormy years the two friends ... had come to a parting of the ways."

Goering and Himmler, who each detested Roehm for his own reasons, would soon provide Hitler with "secret" information about plots and conspiracies on the part of the SA to overthrow Hitler's regime. Although it was always known that many of the leaders of the SA were "sexual perverts and convicted murderers", Hitler was soon to declare, "for their corrupt morals alone these men deserved to die".

This was the signal for Hitler, Goering and Himmler to plan a campaign of terror and murder that became known as the "blood purge" of June 30, 1934. Hitler ordered Roehm to be arrested and to be brought to the Stadelheim prison in Munich, the same prison in which he had served time, ten years before, for the part he played in the Beer Hall Putsch. Hitler gave orders that a pistol be left with Roehm in his cell. He would know what to do with it. Roehm refused to use it whereupon two men entered his cell and shot him at point-blank range.

In Berlin Goering and Himmler had 150 leaders of the SA shot against a wall by firing squads. But this was not all. Nobody would ever know how many people died in this blood purge. Germany had a taste of Hitler's methods of dealing with his opponents once he wielded sufficient power.

Hitler had done what was required of him by the President. He had stopped the rot in no uncertain manner. Hindenburg thanked him for his "determined and gallant personal intervention ... which rescued the German people from great danger".

The president died on August 2, 1934. Within hours it was announced that Adolf Hitler had taken over the powers of the Head of the State and Commander in Chief of the Armed Forces. The title of President was abolished. Hitler would be known as Fuhrer and Reich Chancellor. His dictatorship had become complete.

All officers and men of the armed forces had to swear allegiance to Adolf Hitler, not to anything as vague as "The State". Hitler was 45 years old. He was ready to do what Mein Kampf said he would do and what he had explained "in a hundred speeches which had gone unnoticed or unheeded or been ridiculed - by almost everyone - within and especially without the Third Reich".

The time had come for him to consolidate what had been achieved thus far and to intensify the Nazification of Germany in the churches, the schools, the youth movements, the cultural life of the people, the press, the radio and the cinemas, the labour unions, the courts of justice and in the art of Jew-baiting.

He had set his foot firmly on the road towards proving the truth of Lord Acton's crisp saying: "Power tends to corrupt and absolute power corrupts absolutely".

Almost exactly one year after we were married, our home life ended abruptly in common with that of so many others, very often with far greater disrupting results. Our furniture was stored in Durban. When would it ever be used again? The future was one great uncertainty. I was in the army and my wife went back to her father's home. She was awaiting the arrival of our first child who was born on October 25, 1940, six years before her younger sister was to come on the scene. I managed to get leave from the army for a few days after this important event in our lives.

Again I cursed the point in time when Hitler interfered in our lives; again I tried hard to count our blessings in comparison with people whose lives were cruelly shattered in thousands of homes in numerous places. I went back to the army.

What I knew about modern warfare when I joined the army was dangerous but that was of no consequence. What was of immense consequence was that those who ought to have known did not appear to know either. What purpose was bush cart upon bush cart to serve in a modern war? Why those obsolete machine guns that we had to dismantle and assemble? Why those outdated popguns that were supposed to fire armour-piercing bullets? Why leaking tin cans in which to transport precious fuel? Why did we have to parade like ragamuffins in civilian clothes for quite a time before uniforms of some kind arrived?

It was easy to become highly indignant about conditions in the army. But was any Western country prepared for war? Did those countries apart from Germany and Italy, make any serious attempt to introduce compulsory military training? Who gave thought, once again, to spending millions upon millions on getting armed to the teeth? Few could stomach the thought of a repetition of what they had experienced, when in the forces which opposed each other, a staggering total of seven million men died; when more than twenty-one million were wounded; when more than seven million became prisoners of war or whose whereabouts could not be traced; when troops fought, over the bodies of the dead and the dying; when untold misery was suffered in slush and mud in the trenches which were the homes of millions; when fighting had to be resumed over the same terrain, when putrefaction of the corpses had already set in, because the task of movlng the dead had ceased to be possible; when the amputated limbs of the wounded were piled high at casualty clearing stations or in hospitals; when all this was untranslatable In terms of individual suffering; untranslatable in terms of sorrow of the bereaved; untranslatable in terms of waste of human lives when the flower of the nations died.

What is there in the makeup of a man who himself had witnessed and experienced all this for four long years and was now prepared to have it all over again and to subject his people to it once more? To Hitler this was no puzzling question. Germany was not beaten. When victory was in sight, she was betrayed and stabbed in the back. Scores had to be adjusted. "Never in the history of human conflict", to borrow a phrase from Churchill, was there for Hitler a price too high to pay to gain that victory out of which Germany had previously been cheated.

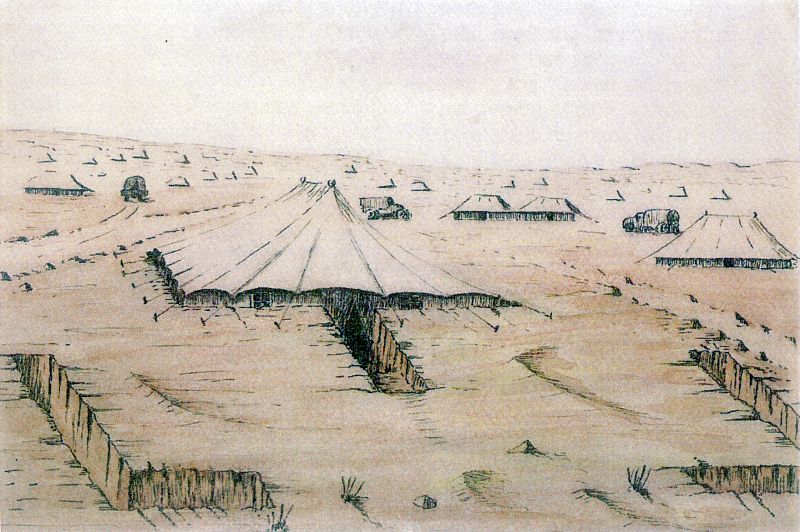

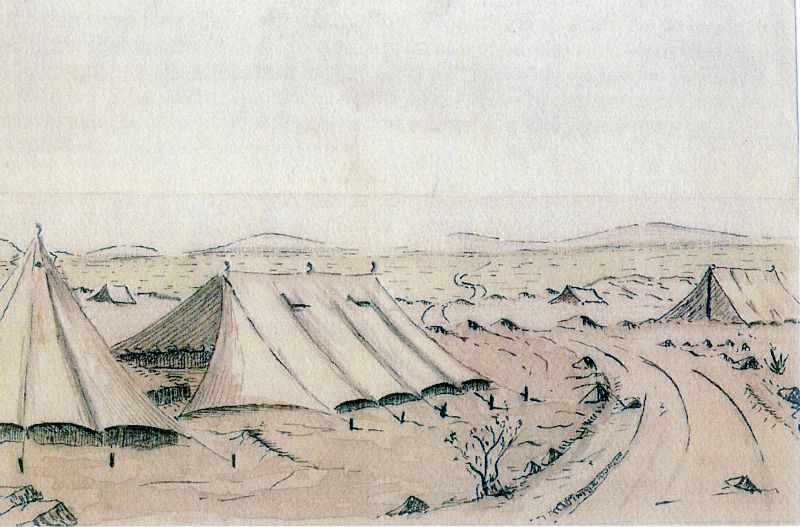

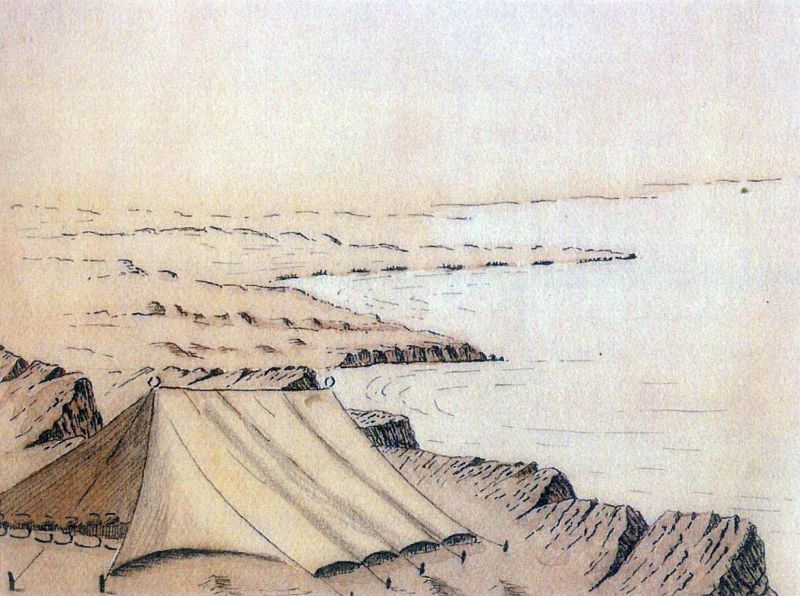

South Africa was also not prepared for war. She had merely followed suit. She too did not relish the thought of a repetition of a Delville Wood if it could be avoided. At Piet Retief we carted damp soil in wheelbarrows into the bungalows which were being built. We stamped the soil down to form a hard surface and slept on it on paliasses stuffed with straw. In the mornings we had breakfast at trestle tables from which the frost could be scraped in handfuls. There were water taps out in the open where ablution activities could take place. Fine! This was good initiation stuff for soft recruits who needed much toughening up before they would even start to look like soldiers. However, when more men started to report to the medical tent in the mornings than to the sergeant major on parade, then it might possibly be that something was being overdone. It did dawn on somebody at last. Two large marquee tents arrived in which the worst of the 'flu patients could be treated under reasonably satisfactory conditions.

Brothers-in-law - Ken Hackland, August 1940, above, Alan Hackland 1941, below

At first I was ill adjusted to some of the irritations, which we experienced. There were corporals from the permanent force who bawled and shouted at us and who thought that swearing at us was a sign of he-man-ship. They were obviously too raw to deal with the situation they had to face. The so-called lecture periods in between parades and other chores were pathetic affairs. Those who had to lecture to us carried little military manuals with them from which they had gleaned something about elementaries for rookies - a little about hygiene, a little about camouflage, about musketry, about badges of rank, about saluting and so on.

We did hear from the hygiene expert that one was to use three sheets from a toilet roll; one for up, one for down and one for polish! Of course, we charged and stabbed gaping holes in effigies of soldiers who could not resist. We gave our bayonets a twist to make the stab all the more deadly. I was impressed by the organisation, which is basic in an army. Theoretically, no hitches can occur in the operational field. Communications flow from the dizzy heights down through armies, to corps, to divisions, to brigades, to battalions, to companies, to platoons, to the loneliest section post where the flag is kept flying. Communications do not work so well in reverse when that section post has to convey something up the line.

We soon appreciated that we were all in an army organisation, which would have to make super-human efforts if we were ever to play anything like a significant role in the task to which it had committed itself.

More Piet Retief photos

To make matters worse, there was no united war effort in this land. The people were split disastrously into two camps. People joined or did not join the army in accordance with the dictates of their own convictions. There was no conscription to fight outside the borders of South Africa. It was a volunteer army and volunteers wore red tabs on their shoulder straps. The opposition in parliament would have nothing to do with the war efforts of the Imperialist, Jan Smuts. Afrikaans-speaking families, particularly, were once again divided in their loyalties.

My mother had a photograph of one of my brothers, as ardent a member of the Ossewabrandwag as ever there was. This photo hung in a prominent place for all to see when they entered the house. He had a luxurious beard. In his hand he held a pipe on the bowl of which an Anglo-Boer War prisoner in Ceylon or Bermuda had carved the coat of arms of the South African Republic. It was a treasured possession from bygone days. Next to this photograph, my mother had one of me dressed in a khaki uniform. The orange tab on my shoulder would have stood out like a red rag to a bull if it had been in colour. My mother must have hung these photographs the way she did with a heavy heart to indicate to visitors that they had entered a house divided against itself.

My parents were married a few years after my father returned from the Anglo-Boer War. He had heeded the call of General Smuts when he made his raid into the Cape Colony to stir people to become freedom fighters to assist the republics in the north. My father joined the commandos of Commandant Scheepers. He was captured a few days before the war ended and so escaped being tried or possibly shot as a rebel as others were. He was a follower of Jan Smuts. But those were different times and other days. That was the Jan Smuts who could write The Century of Injustice to boost the Boer cause. Since then, believed his opponents, he had strayed and was now completely lost to the Afrikaner cause, together with all those Afrikaners who joined his volunteer army.

In a way I could not understand why it was so very right to have fought injustices committed at other times in this place and so very wrong to fight injustices committed at this time in other places. Yet, it seems to be so that the misfortunes suffered by people not of one's own kith and kin affect one but little.

Some of those who were opposed to South Africa's war effort were openly pro-Nazi. They were proud of it and proclaimed it openly. They were admirers of Hitler. Whereas early Nazi victories saddened one section of the population and caused them to grit their teeth all the more in the face of the great odds which confronted them, this section could in no way forbear to cheer for their hearts were filled with joy and ecstasy. These people were astonishingly well acquainted with the contents of Hitler's speeches, more particularly his periodic peace speeches with which he seldom failed to impress those who were not unduly concerned about his logic or veracity. It was not Germany that perpetuated the war. Those nations who had persistently refused to accept his protection or his peace proposals must bear the responsibility for escalating the war.

There were those who denied emphatically that they were pro-Nazi or approved of all Hitler's methods, although they admitted to having sympathy with Germany over the injustices of the Treaty of Versailles. It was an easy way out to say it was the old, old story of peace treaties at which the seeds of subsequent wars were sown. It became particularly fashionable to deny being pro-Nazi, after Hitler's brutal attack on Holland, on May 10, 1940. It came nearer to kith and kin. They were first and foremost pro-South Africa. They could not see how interference in the affairs of faraway Europe could benefit South Africa in any way. It could only lead to involvement far beyond what was immediately apparent. Millions of people in France and even in Britain had similar fears about getting involved in affairs beyond the Rhine.

Others argued that there were no immediate dangers. Millions in the United States thought so too. How else could the US have declared her neutrality on the very day that the Smuts government thought it fit to declare war?

Below it all there simmered an awareness of nationhood. It received a new impetus in the remarkable year 1938, during the Centenary celebrations of the Great Trek. This fervour could not be dissipated by being channelled into participation in a war unrelated to the sentiments of the people. It was our membership of the British Commonwealth of Nations that involved us in the moral obligation to help Great Britain to pull her chestnuts out of the fire. Thoughts of a free and independent South African Republic were foremost in the minds of many people. To this end they would use their energies. Anybody who has any doubt about the nature of this deep-seated desire for a republic would have their doubts expelled by reading a book entitled Die Republiek van Suid-Afrika, edited by F.A. van Jaarsveld and G.D. Scholtz.

Such were some of the thoughts, emotions and sentiments of a large section of the population throughout the period during which others were heavily involved in a world-wide attempt to stop a tide of violence which threatened to engulf the world at the dictates of a man of evil genius.

We were supposed to have horses at Piet Retief. They never arrived and we were trained along infantry lines. After some months the fodder arrived but the horses went to Ladysmith. We loaded the fodder on a train and also went to Ladysmith. No one regretted leaving Piet Retief. Conditions were much more pleasant at Ladysmith. We lived in decent bungalows. There was even a YMCA in the camp. Horses were a nuisance although the unruly ones provided quite a bit of fun. It soon became apparent that nothing would come of a mounted unit in that day and age, although horses were to bear a considerable burden even in the highly mechanised German army, when Russia was attacked.

Gradually the men were drafted into various other branches of the army and the training programme at Ladysmith changed in character.

At this stage I was instructed to report to Robert's Heights, since translated into Voortrekker Hoogte. (Far better, it was thought, to be reminded of an epic historic event than of a Bntish Lord who had no right to have been here in the first place.) At the Heights I learned that I was to attend an Information Officer's Course. I had no idea what it was all about. I had reached the exalted rank of lance corporal at Ladysmith. At the course I found a rather intellectual-looking group of people. There were some senior non-commissioned officers and non-descripts like myself. There were lieutenants, a sprinkling of captains, a major or two and at least one colonel. They were from all walks of life. There were lawyers, schoolmasters, and university lecturers in a great variety of subjects, extension officers and others. They were rather an interesting group.

We were to prove our ability, or lack of it, to give talks to audiences on a great variety of topics amongst which were included all the -isms under the sun, like imperialism, colonialism, nationalism, communism, socialism, nazism, fascism and for good measure, Catholicism, Protestantism and Mohammedanism.

Most people giving talks on these subjects, seemed to me to know their subject matter very well and were, to my mind, talking sense and saying provocative things which did not fail to lead to stimulating discussions. We were dealing with policies and ideologies, forces that were shaping the world around us and from which one could hardly escape. Could they be evaluated objectively and impassionately? What paths were there to follow in a world, which had once more gone crazy in the pursuit of -isms old and brand new? Who could label the correct road to take?

In our discussions of these controversial topics, which tended to produce more questions than answers, I inevitably thought of the dilemma, which faced Omar Khayyam when he wrote:

Neither the Doctor (Science) nor the Saint (Religion) could tell him what he wanted to know about the forces that shaped the destinies of man. For us it was a difficult time to know in which direction the world was drifting.

It seemed to me that all the -isms produce leaders who make sure that their followers receive regular transfusions of life-giving hot blood obtained from the blood bank of fanaticism. Not having subjected myself to blood transfusions of this nature, I lacked fervour when approached by those who were enthusiastically engaged in furthering the cause of one or other of the -isms. Every one of them produced their crops of torturing, stake-burnings, beheadings and hounding as well as their martyrs whose sacrifices had to be avenged, thus setting the whole machinery almost in perpetual motion. The one inevitable outcome of the fanaticism inherent in these, often irreconcilable, ideologies and beliefs, is WAR. Was it inevitable that we would have to live with this - always?

I became more perplexed than ever. Was it not too late now to ponder over these things? We were at war over these issues. Nations were lining up in opposing camps for the purpose of smashing into each other with ever-increasing fury. People can find no explanation for such senselessness. What is more disturbing is that history reveals all too often that most military campaigns are characterised by violent quarrels and disagreements amongst those who plan them at the highest levels. The outcome is blundering and confusion at crucial stages, leaving the ordinary soldier to pay the price, often with his life.

No wonder the ordinary soldier wants to know as much as possible "about it and about" before he gets immersed in a sea of struggle, for once in it he has no option but to be taken with the tide in its ebb and flow. It is inevitable that it will not remain indefinitely and unreservedly true of soldiers that:

They would most assuredly want to reason why and make reply. A more rationally calculated approach towards the need for doing and dying could no longer be ignored.

It seemed to me that this was what the course was about that I was instructed to attend. It stemmed from a realisation that volunteer soldiers above all had every reason to probe deeper into the causes of armed conflict as opposed to negotiation, than had been customary in the past. Moreover, ordinary people, not indoctrinated and conditioned were getting extremely tired of sentiments of the nature expressed in

and in

and in many others equally unacceptable to rational beings. Sentiments of this nature would stir them not, however much they stirred people in bygone days.

Why then were we at war?

A story is told of an Arab chieftain whose forces had occupied the city of Alexandria in the days when the Islamic faith was spreading in the Middle East. The soldiers wanted to know from their commander what they had to do with the books in the Alexandria library. He is supposed to have replied that if those books supported the Koran, then they were superfluous. It they contradicted the Koran, then they were dangerous: "Burn the Books".

At this course we tried hard not to fall victims to an attitude of mind that we abhorred in others - to see one point of view only. But we had been at war for more than a year. The issues involved had been discussed ad nauseam. The world was dealing with a blinkered individual who, too, had literally and figuratively ordered the burning of books superfluous or contradictory to Mein Kampf. By 1940 over six million copies of this book had been sold, mostly in Germany. It was almost expected of people to present copies of the book to people getting married, having birthdays, doing well at school and on other occasions: a home without a copy was suspect. One point of view had to prevail and implicit in that point of view was the need for violence. As always, violence could only be stopped by counter-violence. To such a sorry pass the world had come once more.

Great guilt must surely rest on any regime, anywhere, which sets out to condition and indoctrinate Its people, especially the young, into wearing blinkers that make them see only what they are told to look at.

Greater still is the guilt when such a people is propagandised by every means to the extent that they will, without question, march into war with buoyancy in their steps and joy in their hearts, with the object of denying to, and grabbing from, others, what they demand for themselves as an inviolable right.

I found the course interesting, stimulating and enlightening. I certainly benefited from it more than I would have from pulverising a parade ground still further under my boots, boots, boots. I could do that quite well and the ability to do that would soon be of little consequence.

We were told that we would be seconded to various battalions and regiments. The NCOs amongst us who qualified, would hold the rank of lieutenant. We were to be integrated into these units and share whatever fate was to befall them. We were to stimulate discussion amongst the men concerning what it was all about that they were being called upon to do and if necessary, to die for.

At the end of the course I was seconded to one of the battalions that constituted the Sixth Brigade of the Second South African Division.

About this time there were rumours that the Second Division was ready to go "up North". If this were so, my wife and I would have to give final thought to the conditions under which I was to leave her with our young baby. When I talked to my wife recently about it, I was astounded to discover how time had blurred for both of us the details of those far-off days. Perhaps we were rather stunned when, what we had been expecting, suddenly became a reality.

A suggestion that my wife should act as principal of a small primary school in the country, had its advantages in that she would be independent. On the other hand, it would be a tough undertaking. She would have to live in a house by herself, isolated from the rest of the community with no telephone and no transport. Not an attractive alternative. My own qualms were considerable, but in the end our furniture was sent from Durban and I assisted with the settling in. My wife was to attempt it. I left to report to my unit stationed outside Pietermaritzburg.

Some little while afterwards General Smuts came to address a large gathering at the camp, including relatives of the men. We were to have embarkation leave. The old warhorse told the gathering something to the effect that some of us would come back; some of us would come back, maimed; some of us would not come back. A woman fainted behind me. For myself I, did not have to be told that. Mine was already a calculated approach that had taken all that into account. Whatever patriotic embers I had smouldering in my soul could not be fanned into a devouring flame other than by a conviction within myself.

We entrained for Durban in the veld outside Oribi. From Durban I made a dash for a taxi to obtain a friend's car to go and see my wife and daughter. When I arrived there, she had left for Durban, having heard of our impending departure Back I went to Durban. I found her where I expected she might be. What hurrying and scurrying.

We embarked the next day, on June 10, 1941. Our daughter was seven months old. My wife went back to her school where she stayed until it proved impossible to continue. Her father aIso pressed her to come home. We parted, facing a future full of grave possibilities and unpredictable duration - the very things wars have always brought about, and much rawer deals were being experienced elsewhere. What could one's contribution count towards bringing this business to an end as soon as possible?

Perhaps it is not a very soldierly thing to say, but I was not experiencing the youthful exuberance and enthusiasm that popular notions pretend to be true, or believe to be true of soldiers under such circumstances. I was a little older than youthful. I had a career in which I was interested. I did not revel in release from boredom. I did not strain at the leash to leave my home, to come to grips with the enemy, to experience Action, Movement, Adventure, Excitement, with capital letters. I was not particularly glad to be off to see the stuff that wars are made of _ hunger, thirst, fatigue, exhaustion; off to see wounds and blood and muck; off to witness destruction and mutilation; off to see death being meted out to comrades; off, perchance to die in agony or otherwise, but nevertheless, gloriously, for a good cause.

Tradition has it that there is something about a soldier that is fine, fine, fine. Of course there is. Not so much because of what soldiers have to do, for in the nature of things they essentially have to kill, the more the better, but because of what they have to endure - on both sides. That is why a spirit of comradeship and of fellow-feeling, even compassion, can at times be extended to reach across firing lines into enemy territory. That is why soldiers of opposing forces are sometimes less capable of perpetual hatred than politicians in opposite camps. There is something about soldiers that is exceedingly fine when they can do these things:

And something immeasurably fine about those horses too. So, strike up the band:

Thrilling! Splendid! Magnificent! At last we are marching into war. Primitive, but necessary. A "thigh-bone beating on a tin-pan gong", drums, war cries, they all have the same effect. They rouse, they stir, they unify. They pour adrenalin into the blood. They make you act beyond normal capacities. They dope you. They make you see red and once you see red, you do heroic things.

It is all part of the bloodiest game man has played ever since he left the trees to walk on his hind legs, setting his hands free to make weapons with which to kill in order to live, to defend his territory, to attack his adversaries.

The experiences that befall soldiers in times of war can be traced in war records of one kind or another by someone interested in doing sucn things. Minor successes are often depicted as glorious victories and dismal defeats as orderly withdrawals. What happens to mothers, wives and sweehearts who are left behind, is only recorded in the minds of those to whom they are dear. There are no stirring marching songs in which we wish them luck as we wave them goodbye. They often have the harder row to hoe.

The Mauretania was steaming up the north coast, crowded out with thousands of soldiers. She had been stripped of everything luxurious. She was a troopship. Nearby there were two other passenger liners, the Île de France and the Nieu Amsterdam, equally crowded with soldiers. Towards the evening I stood on the deck with hundreds of others gazing at the South African coastline. I had the impression that they were all rather subdued as I was My mind was dwelling on what was probably happening where my wife and daughter were. They had probably arrived home by now. Had my wife prepared supper? Had the baby already been fed and bathed and was she sleeping soundly by now? What thoughts were crowding in on my wife's mind? I hoped she was so exhausted that she would be fast asleep.

Someone touched my arm. "What rubbish people talk", he said. I agreed, but I could only guess what he had in mind. As far as I remember there was no great revelry by night, as we steamed further north. The next morning I was aware of the cruiser HMS Cornwall, roaming far and wide, first nearby and then towards the distant horizon. She was our escort ship and watchdog of the seas.

A cynical philosopher once said something to the effect that he wished mankind had but one neck so that he could conveniently cut its head off. I, also, looked for a single neck that held the heads of all warmongers, war profiteers and militarists who blundered into massacre after massacre with sickening regularity. I would cut it off with one fell swoop.

I soon became engrossed in a number of maps, pamphlets and books about the progress of the war and about the geography and the economic, social and political conditions of the land of the Pharaohs to which we were going under strange circumstances. Perhaps there were agreements or non-agreements about aggression or non-aggression. We were to operate on Egyptian soil apparently without that country having committed herself to either supporting or opposing us. I did not try to unravel it. It became stiflingly hot as we approached the equator and moved into summer conditions in the northern hemisphere. We drank gallons of liquid refreshments. Crowded conditions did not improve matters.