The South African

The South African

Published on the Website of the South African Military History Society in the interest of research into military history

Copyright rugeos@icon.co.za

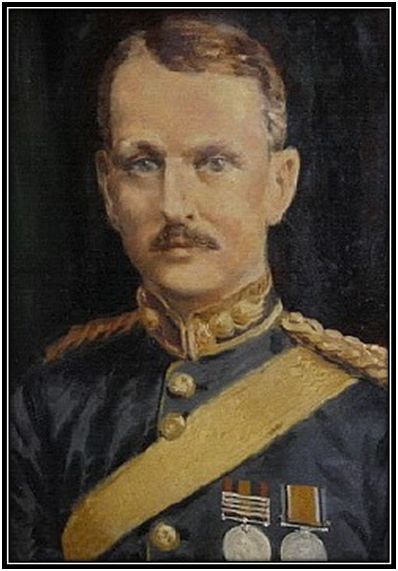

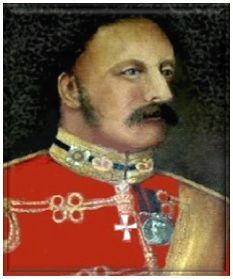

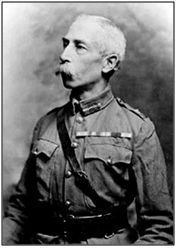

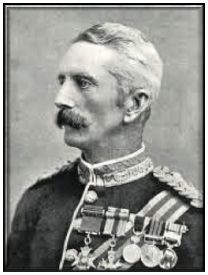

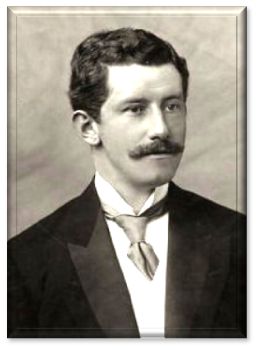

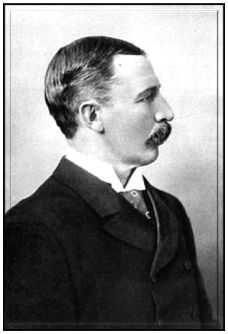

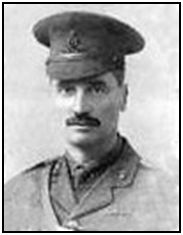

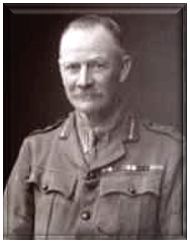

Jocelyn Frederick de Fonblanque Shaw.

Jocelyn Frederick de Fonblanque Shaw was born 28 February 1874 and came from a distinguished and titled Anglo-Irish family. His father, Lt-Col. Wilkinson Jocelyn Shaw, 1834-1911, MA. Trinity College, Dublin, was a career army officer having served with the Royal Dublin Fusiliers including a stint in New Zealand during the Maori Wars. He in turn was the fourth son of Sir Frederick Shaw, 3rd Bt., of Bushy Park, Dublin, 1799-1876, MP., PC., DL., Trinity College, Dublin and Brasenose College, Oxford. Sir Frederick married 1819, Thomasine Emily Jocelyn, daughter of the Hon. George Jocelyn, MP., 1764-1798, and the granddaughter of Robert Jocelyn, 1731-1797, 1st Earl of Roden, all of which explains how Jocelyn Frederick derived his first names. On the maternal side his mother, Lavina Mary de Fonblanque, was descended from a long line of accomplished politicians, lawyers and writers, all originally of French Huguenot stock. Jocelyn Shaw died 28 June 1936, aged 62.

,

,

Lt-Col. Wilkinson Jocelyn Shaw, 1834-1911. Sir Frederick Shaw, 3rd Bt., 1799-1876

Little is known of Jocelyn Shaw's youth and upbringing. His father married relatively late in life, aged 38, and with his army commitments would have been away from the home and family for long periods of time while on active duty. This would suggest that the father/son relationship was at arm's length and impersonal, the responsibility for his raising falling mainly to his mother. He did have a sister, Esm&êcirc; Mary, nine years his junior, with whom he could hardly have established a close relationship and would therefore effectively have been raised as a single child. He did however, for a short period anyway, 1888/1889, attend the prestigious Cheltenham College, in Gloucestershire so would appear to have received a good education.

Cheltenham College.

Money in the family would have been in short supply, as is evidenced in the diary that follows by his father having scraped together £5 which he sent to his son in South Africa after the closure of the mine for which he had been working in Johannesburg. While a thoughtful and considerate gesture it would hardly have kept body and soul together for any length of time but was presumably all that his father could afford. The state of the family finances are again highlighted later in the diary when Jocelyn Shaw was deliberating on the question as to whether to accept the army commission which had been offered to him. He states unabashedly that he would have to make ends meet entirely on his rate of pay as a 2nd Lieutenant as his father was in no position to supplement his income. One can safely assume that it was largely because of the modest home environment in which his parents were living, his father by then having retired, which motivated the son to strike out on his own and to try his luck on the Johannesburg gold fields which is where the diary commences.

The story behind the diary is almost as interesting as the diary itself. An enormous volume of literature was generated as a result of the Boer War, much of it in official reports and later books written by the major participants. It was a war that garnered daily interest around the world and was the first to involve participants on a truly global scale. With Great Britain's pre-eminence and colonial loyalties, large contingents were shipped half way across the world from Australia, New Zealand, and Canada to fight the homeland cause. Even neighbouring Rhodesia managed to raise an impressive force in response to the call to arms. And while the war was essentially a British/Boer Republic conflict let it not be forgotten that South Africa saw the raising of numerous volunteer regiments including the very one to which Jocelyn Shaw signed up, the Imperial Light Infantry, or its sister mounted regiment. The long established Cape Mounted Riflemen, garrisoned in King Williams Town which was heavily engaged in the Wittebergen is another prime example.

Not that the Boers were without their supporters and sympathisers either with European sentiment, especially that of Germany, France, the Low Countries and Scandinavia, being solidly pro-Boer. This saw a flood of volunteers, mercenaries and fortune seekers who threw in their lot with the Boers, some on principle but others as opportunists. The most well organized and equipped of these forces was the Irish Brigade,(mentioned in the diary) who were motivated by their deep-seated hatred of everything English for the injustices meted out to Ireland over the centuries, personified by their stigmatized ogre, Oliver Cromwell!

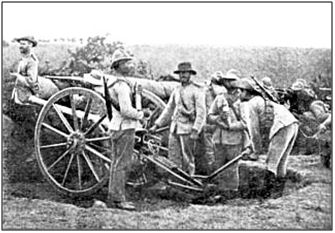

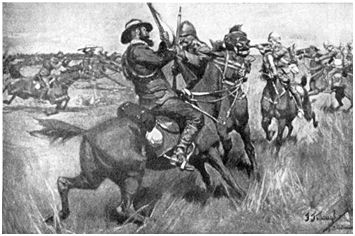

Another aspect of the war that fed into the public imagination was the "David and Goliath" nature of the combatants. Here was the then greatest military power on earth steeped in the tradition of Horatio Nelson and the Duke of Wellington taking on what was essentially a rag-tag bunch of renegade farmers. The fight would have been a lot more one-sided were it not for a number of factors that worked to the Boer advantage. In the first instance they were people of the land who were brought up in the saddle and were intimately familiar with the territory over which they roamed. They were also excellent marksman having been brought up from virtual infancy in the use of firearms. But, overriding all else was the foresight of Boer President, Paul Kruger, in the wake of the Jameson Raid ordering 50,000 of the very latest German Model 1893/ 1895 Mauser rifles and vast quantities of smokeless 5 X 57 cartridges. It is estimated that by the time the first shots were fired the Boers had accumulated a stockpile of fifty million cartridges of all kinds. Taken together with a modern array of artillery pieces in the form of the French Creusot, the "Long Tom", and various German Krupp canon, the Boers were at least a match for the British when it came to firepower.

It was into this whole mixing bowl of circumstances and conflict that Jocelyn Shaw was pitchforked in September 1899 when the rug, represented by what appears to have been a cushy job on a Johannesburg gold mine, was pulled out from under his feet as a result of the gathering war clouds. As an adventurous young man he had come out to the Witwatersrand a year or two earlier, attracted in large part by a wage scale which, by his own admission (detailed in the diary) was much higher than that on offer in London and in the realistic expectation of bettering himself. He was by every definition of the word, an "Uitlander" (foreigners, mainly of British descent) from whom, as a group, all political rights were withheld by the Transvaal (Boer) republic based thirty-five miles to the north in Pretoria.

But in the immortal words of Robbie Burns about the best laid schemes o' mice and men ganging aft agley, Jocelyn Shaw suddenly found himself both unemployed and homeless. To his credit he decided to make his own stand by throwing in his lot with his British countrymen, finding his way to Durban via Lourenço Marques and after hostilities began by volunteering to serve with the Imperial Light infantry. Whereas it is unlikely that he would otherwise have joined the military it was by this complete quirk of fate that Jocelyn Shaw ended up in uniform, a career to which he seems to have been well suited and in which calling he appears to have been perfectly contented. Thereafter he served in the British Army, Royal Artillery, for the next twenty-two years ending up with the rank of Major.

As to how the diary came to light, all credit needs to be given to Jocelyn Shaw's grandson, John Shaw, now living in Los Angeles. John, one of three brothers, is the son of Jocelyn Frederick Basil Shaw, 1923-2012, in turn the son, and only child of Jocelyn Shaw Sr. Jocelyn Shaw Jr. was educated at Wellington College,

Wellington College.

and King's College, London. He later studied at the universities of Oklahoma and Miami from which he graduated with a PhD in Civil Engineering. He worked mainly as a consulting engineer and in academia ending up at the University of Wyoming, in Laramie where he eventually retired and later died in 2012. It was during the process of sorting through Jocelyn Shaw Jr.'s personal possessions that the diary came to light and was in due course taken over by John Shaw. He soon came to the realization that it represented not only a valuable and intimate family heirloom but in addition, certainly as it applies to the Boer War, a hitherto completely unknown and detailed personal account of aspects of the war which would be of tremendous interest to military historians. For these reasons John Shaw undertook a verbatim transcription of the diary which he has posted on the Internet for the benefit of interested parties to which he has added his own "Foreword" which is repeated below for record purposes.

By John Shaw, Grandson of the Author

This is an account of one soldier's "war stories" about his life while in British military service from September 1899 to January 1902. It is not a tale of great adventure and fortune, but instead a tale of an everyday solider slogging it out as a private and later as a low ranking officer (Subaltern). Still, while employing a simple unassuming nature, it is clear the author had a gift for summing up the essence of each turn of events, and I found myself at times excited as he described the run up to, and unfolding of, the battles he participated in, laughing at the humorous anecdotes he remarks on, and even shed a tear at a somber moment he experiences in a hospital.

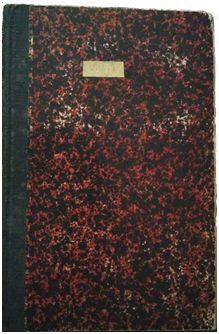

The work was handwritten in a journal I inherited when my father passed in 2012. I found it hard to read, as cursive handwriting has largely become a thing of the past, and so decided to transcribe it to a text file to make it easier to digest and share with other members of the family. My hope is that by publishing it here, the legacy of my Grandfather can be discovered and enjoyed by his offspring for years to come.

Having never known my Grandfather, prior to this work, the only stories I had of his existence was the bits of information my father leaked out from time to time. Of course my father didn't get a chance to know him all that well himself, as he died when my father was thirteen years old. Among these bits were that he met and married an English woman (May Kenward) in Jamaica. They moved to Monte Carlo (Monaco) together. There they cashed in, or sold, half of his officers pension to open a tea shop. They had a son, my father (Jocelyn), then about four years later his wife died. Sometime after this he took his son and moved to Rouen, France. It would have been there that he wrote this work at age 59. Two or three years later he died, possibly of tuberculosis.

It's not much to know about a man. Yet it is more typical than not that this kind of scarce information is all that remains a generation or so after one's death.

So as I was going through the transcription, I was delighted to meet this person, and to really get a sense of the kind of character he was. Although there are a few words (I count two) that in today's usage would be considered derogatory, it seems he was quite an open minded thinker and displayed a noted lack of prejudice for the times. The work reveals a person who is honest, worldly, intelligent and who keeps a keen eye on finances, no doubt owing to his low military pay.

This last trait makes for especially interesting reading as he includes many wages and prices of the time. In most cases I have included the conversion from shillings/pence to the decimal equivalent in pounds to make it easier to understand the values being quoted. These notes, and any other notes I added, are in italics. High quality images of the handwritten pages of the journal appear to the right, roughly lining up with the corresponding text.

I hope all who read this find it as interesting and as enjoyable as I have.

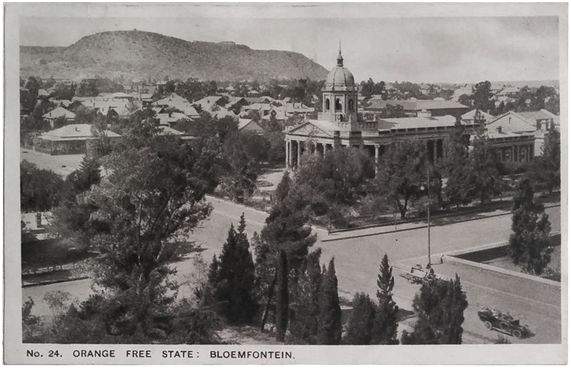

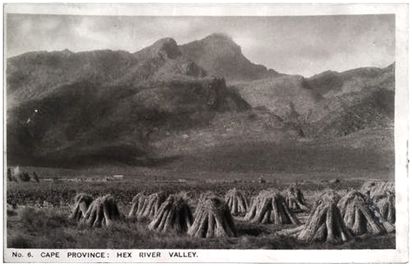

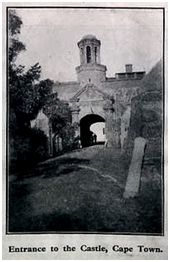

One notable feature of the diary is that it was written so long after the event as explained by John Shaw in his Foreword. Given the immediacy of the language and the attention to detail this seems an extraordinary feat of memory. The only explanation is that the author must have made detailed notes at the time which he retained and used all those years later to refresh his memory and as reference points. This is confirmed by the fact that he kept all the postcards that he collected during his travels throughout South Africa which he later inserted amongst the text where appropriate which the compiler of this transcription has duly repeated.

Diary front cover.

Illustrated above is the front cover of the actual diary, on which a sticker has been affixed which reads, "Vol 1". This volume begins with a detailed summary of everything written by Jocelyn Shaw covering what he described as "Twenty-two years of soldiering in Peace and War" which, as the Index makes clear ran to a full five volumes, shown in the extract below. What all this means is that the portion of Jocelyn Shaw's diary covering the Boer War included under his "Chapter 1" represents only a small portion of his writings as a whole. The other four volumes have never been located and are presumed lost.

Front page.

This transcriber is not overly concerned as to this state of affairs as his interest lies almost exclusively in the experiences and descriptions of Jocelyn Shaw during the Boer War to which should be added the fact that this was the only occasion during the twenty-two years that the author saw action in the field. As for the rest, his responsibilities were largely of an administrative and staff nature including the four years of the First World War which while of general interest would have been more routine in nature.

In the matter of September 1899, I held a position in the Cyanide Works of a gold mining company in Johannesburg, South Africa. At this period, war with the South African Republic [the Transvaal] was regarded as a certainty. [This opinion was widely held and is supported by three critical developments that month.

1) 8 September 1899. The decision of the British government to send 10,000 troops to defend the Natal colony.

2) 26 September 1899. The decision by Major-General William Penn Symons, GOC (General Officer Commanding) all forces in Natal to move his brigade to a forward position at Dundee. He died from wounds the following month at the Battle of Talana Hill.

3) 27 September 1899. The decision of President Paul Kruger to call for a general mobilization of all Boers in the Transvaal. President Steyn of the Boer controlled republic of the Orange Free State did likewise on the same day.]

Johannesburg garden.

The Bloemfontein Conference [held 31 May to 6 June 1899 between Sir Alfred Milner, British High Commissioner and President Paul Kruger] had ended in a deadlock. The British government, having allowed itself to be unduly influenced by a gang of Jew and American financiers serving their own ends had expected its determination to be "firm", as far as affairs in the Transvaal were concerned.

[The most prominent of the Johannesburg Jewish community at the time would have been Alfred Beit, 1853-1906, (Wernher & Beit & Co.), below left, a wealthy diamond and gold magnate who was very active at the time in his support of the Uitlander cause. In addition there was the colourful Sammy Marks, below middle, and Barney Barnato, below right, a charismatic person of humble London, Whitechapel, origins who made a fortune in the gold and diamond mining industry in competition with Cecil John Rhodes as well as others engaged in the newspaper business and the professions.]

,

,  ,

,

Beit, Marks, Barnato.

If, however their warlike preparations were regarded with favor by the capitalists they were received with very different feelings by the working community. The main excuses for bringing about a state of war were firstly, the excessive taxation and high cost of living and production which affected the mining industry and secondly, the alleged lowering of British prestige by the insults offered to British subjects by the Boer government.

But we of the working community had little to complain of under the burgher rule! Wages were high and compared favorably with other countries. Taking my case, I was getting from £20-0-0 [20 pounds, 0 shillings, 0 pence] a month as a minimum to £25-0-0 as a maximum, as a young man[of] 24 in the Cyanide works of a gold mine which was quite three time as much as I could have earned in a London office. Also I received free quarters. For messing [meals] I paid £8-0-0 a month, so I was living well within my income and other trades were paid in similar proportion. Stonemasons & carpenters earned £30-0-0 a day, fitters £20-0-0 whilst two miners, working under ground in partnership (on day and night shifts), could easily make £70-0-0 a month each! And again we found, that so long as we kept the law, and behaved ourselves as good citizens should, we suffered no insults or inconveniences, from the Boers. In addition, we fully realized that a restoration of the Transvaal to British rule would be entirely for the benefit of the capitalist and a general all around reduction of wages would most certainly result. So it is scarcely to be wondered at if we were not very enthusiastic over the prospects of a campaign! These were the whites' views in 1899.

But since this date their ideas on the subject have entirely altered! For the importance of incorporating in the empire the most productive goldfields in the world cannot be overrated!

Johannesburg gold mine.

Meanwhile the military preparations continued on both sides and by the last week in September, many mining properties had closed down, and hundreds of Uitlanders [literally "Outlander", a term for foreigners, mainly British, living in Johannesburg] had left the country.

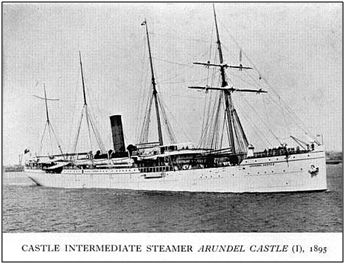

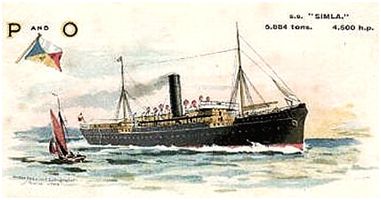

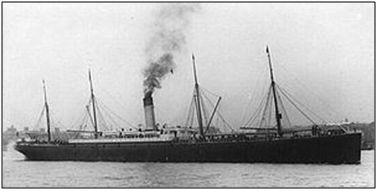

The mine on which I worked suspended operations a day or two before the end of the month, and on the following evening I took the train for Lourenco Marques (Delagoa Bay), this being the only line left open to us at the date, the Boers having seized all the other ones. We travelled packed in cattle trucks - all railway carriages having been commandeered to take the burghers to the front. The journey took about 27 hours and was uncomfortably warm, especially the latter part which was through sub-tropical country. However a good night's rest at the hotel soon restored us. A steamer (the "Arundel Castle") was waiting in the harbour to convey the refugees to Durban. [The Arundel Castle of 4,588 tons was launched in 1895 and was therefore a modern ship for the day. Its only oddity were the two crossed sail beams on her foremast as maneuverability insurance against the failure of her single screwed engine.] We had a few hours, however, to look around the place before embarking. Lourenco Marques we found to be a picturesque town; with a ridge of heights at the back, dotted with red roofed villas peeping out of the green trees. The harbour is one of the finest in the world.

Arundel Castle.

I have no idea of how many of us were accommodated on the "Arundel Castle", but I should judge at least ten times the authorized number of passengers! All we got in the way of accommodations was a place on the deck to lie down and [a] couple of ships blankets. For meals we had to go down in batches. The first day at lunch I must have struck the last batch, for all I could get was a plate of curry and rice. The stewards were in a state bordering on mutiny, at having so many people to look after!

Fortunately, the weather was fair, and in the evening of the second day we made Durban. There in the harbor we found four or five transports, just arrived from Bombay with various infantry and cavalry regiments. The groups were being disembarked as quietly as possible, and pushed up to Northern Natal as rapidly as possible by rail.

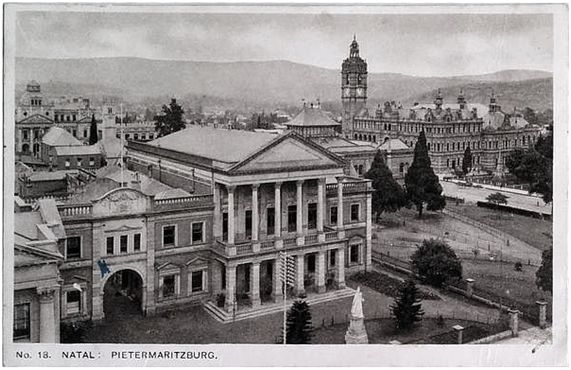

Next morning, after recovering my baggage from the ship, I took the train for Pietermaritzburg, the capital of Natal, and about five hours journey. [Pietermaritzburg is only 42 miles from Durban as the crow flies but is at 2,000 feet above sea level so it would have been a slow up-hill climb by train in 1899]. War was by now officially taken place in the Natal-Transvaal frontier. Having established myself at a boarding house, I proceeded to study the situation, and to decide what was best to be done.

Pietermaritzburg was naturally crammed with people from the Rand, [the Rand a short interpellation of the Witwatersrand or main gold reef. Today it is the name of the South African currency] and it was amusing to listen to the various predictions as to the length of the war. Meanwhile as the days dragged on, the news from the front dribbled down to us, and was none too amazing. The engagement at Dundee, the retreat to Ladysmith, the fight at Elandslaagte and the final investment of Ladysmith, all clearly showed that we had failed to realize the magnitude of the job England had taken on!

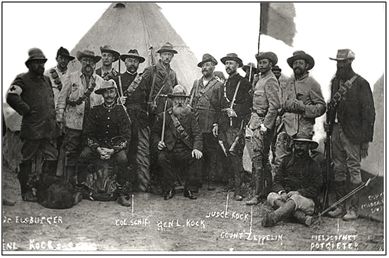

[Elandslaagte was the first battle of any significance the start of the Boer War. A Boer commando under General Kock, see photograph of him and his staff, below, seized the railway station on the line between Ladysmith and Dundee. Major General French, see bottom previous page, (later Field Marshal Sir John French Commander in Chief of the British Expeditionary Force during the first eighteen months of WWI) was sent out to confront Kock which he did successfully although with a much larger force suffering in the process almost twice as many casualties.]

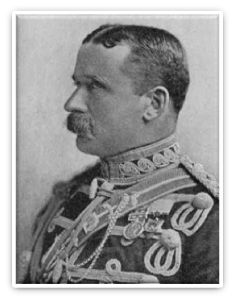

Major General French.

General Kock's Boer commando.

I spent a month at Pietermaritzburg, and then seeing no prospects of an early termination of the war, I decided to "join up." The corps I selected was the Imperial Light Infantry, which was just then being raised at Durban and also at the capital. Having successfully passed the doctor, I, with others, was allotted a railway warrant to Durban, where the battalion was to be trained at first. Whilst waiting for the train, I proceeded to take stock of my future comrades-in-arms, with the view of seeing what sort of "cannon fodder" we would be likely to make. They appeared to comprise all grades of society but the majority were of the working classes. Here and there, a medal ribbon denoted the old soldier. Before entering the train, the role was called by an official from the enlistment bureau.

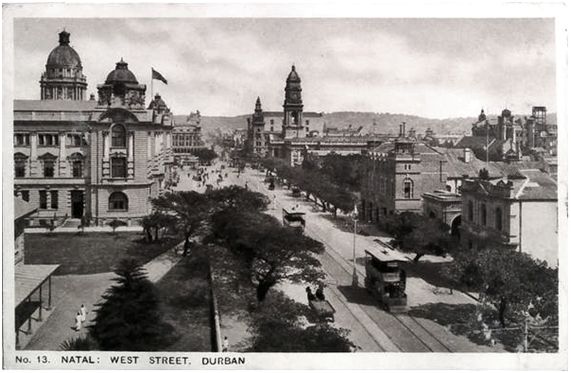

Pietermaritzburg.

On reaching Durban, we found the adjutant awaiting us on the platform. We were very soon formed into fours, and conducted to the camps, where the commanding officer made a brief inspection. The role was then called again apparently to see if anybody had deserted en route. This done, the Quartermaster told us off to companies and we were dismissed to our tents!

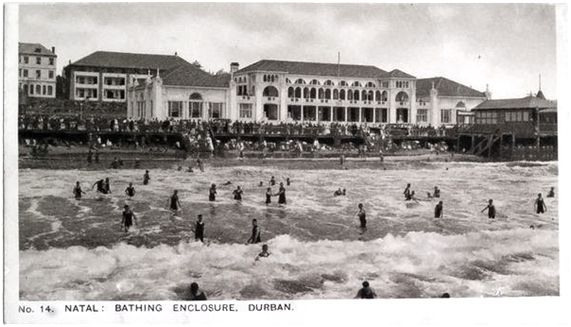

Durban.

The Imperial Light Infantry consisted of eight companies on the lines of a regular infantry battalion, with a strength of over 1000 of all ranks. With the exception of the C. O. & adjutant, who were regulars, the officers were for the most part without military experience. Amongst the "other ranks", however there was a fair sprinkling of men who had soldiered in some form or other previously. For my part I had held a subaltern commission in the Militia at home for these years, and others had served in the Volunteers, or in colonial corps in S. Africa, and a few had even been in the ranks of the regular army.

I found myself posted to "C" company, and having discovered my tent, proceeded to help the others to settle down! 15 men were allotted to a bell tent, which was rather a square. Each man lay at night with his feet to the pole using his kit as a pillow. The rifles (when issued later) were strapped to the tent pole. Fortunately, all the men in my tent (with one exception) were clean, sober, and respectable fellows, and contributed to make things as comfortable as possible. As regards the one exception, he showed a decided tendency to return to the tent at the hour appointed for "lights out" in that condition best known in the military parlance as "Unfit to go on guard" at the same time experiencing a desire to fight everybody in the tent.

However, certain decidedly firm, not to say drastic, measures taken, prevailed and a day or two later our friend found it expedient to apply for a transfer to another company, which was granted. From this time onwards, we were quite a happy family!

As regards bedding, each man was issued with 2 army blankets and a waterproof sheet. The latter about 6ft [feet] by 3 ft was intended to lie on at night, and no doubt saved many lives from the effects of exposure to damp. This however, was all the equipment we received so far.

Reveille next morning sounded sharp at 6.0 am, and we hastily rose, for there was not a moment to lose! Parade was to 6:30, and we had to wash, shave, dress, square up our bedding, and be out on parade in half an hour. The washing arrangements in camp were as yet primitive and consisted of a pond at the top of the field where the camp was pitched. At 6.30, the battalion fell in by companies on the parade ground, and review for the first time we made the acquaintance of our company officers. This first parade was devoted to selecting suitable "Non-Cons" from the ranks. We of "C" company were fortunate in this respect, and secured an excellent colour sergeant, in addition to some good sergeants and corporals.

At 7.30, the parade was dismissed, and at 8.0 breakfasts were served. This meal consisted of a pint of coffee per man with as much of the days bread ration as he cared to consume. As regards the daily ration there in the field amounted to 1 lb [pound] of bread, 1 lb of fresh or tinned meat and 1 lb of potatoes or preserved vegetables. In addition, a grocery ration of small quantities of coffee, tea, sugar, salt and pepper, was issued. As the war progressed however, the field rations were considerably improved and much luxuries as bacon, jam and cheese were included. For the moment, there was a "dry" canteen in camp, where milk, butter, eggs, sardines etc. could be bought at very moderate prices. As we of the I.L.I. drew pay at 4/6 a day, or against the 1/0 of the regular soldier, we could well afford to supplement our ration in this respect and lived on the whole very well. Also we were allowed to buy beer at the "wet" canteen to the extent of a 2 pints a day, one at 12.00 noon and the other in the evening (6.0 pm to 9.0 pm.)

Breakfasts over, we were summoned by bugle to the second parade at 9.0 AM. All that is to say [everyone] except the tent orderly, who remained behind. This duty was taken daily in turn by all privates. The duties kept him pretty busy. Having tidied up the tent, he was hurried off to the cookhouse, to peel the 15 lbs of potatoes drawn by the mess. Then he had to clean out the large oval camp kettle in which the breakfast coffee had been made, and fill it with clean water for the dinner meal. At 12.45 pm he fetched the dinner from the cookhouse, and divided them out to the 15 men. After dinner, he had the washing up to do, and clean out the kettle and again fill it with fresh water for the tea meal, which was served at 4.0 pm. He was also held responsible for the tidying of the ground in the immediate vicinity of the tent, and had to take their meals to any men of the tent who might be confined in the guard room. In fact, he generally went to bed at night with the comforting reflection that he had earned his pay!

At 10.0 am, after an hour's elementary drill, we were dismissed for an hour's respite. From 11.0 to 12.0 another hours drill as above. Then "beer parade." Dinners were served at 12.45, and consisted as a rule of a meat stew, with potatoes or vegetables.

For the first day or two, we were rather restricted in the way of knives, forks, plates etc. The "free kit" as issued to the regular soldier, and which we had been provided, did not arrive for many months. But more of this later! So we judged it expedient to make ourselves comfortable in this respect by the expenditure of a little money, and our wise in are decisions. The forth [fourth] and last parade of the day was from 2.0 to 3.0 pm after which our time was our own for the rest of the day, except for men on guard or other duty. After tea [described by the author as "The tea meal comprised a pint of tea per man, with the remainder of the bread ration."] any well-educated man could always get a pass to go into the town until 10.0 pm. At 10.15, "Lights out" sounded and the camp settled down to slumber.

On the third day after arrival at Durban, the battalion paraded for the ceremony of "swearing in". Up-to-date we had only been provisionally enlisted, and were bound by no oath of allegiance! The ceremony was performed by a magistrate, who took us by sections, & we duly took oath "to serve H. M. The Queen for 18 months, or for much longer period as might be required of us." This latter rather vague phrase, however, was regarded with suspicion by many, who seemed to consider that they had bound themselves down for the term of their natural lives!

Our daily parades, as described above, continued with monotonous regularity. The only variation being a bathing parade in the sea, three times a week. Up-to-date, having received no uniform, we had to perform all drills & duties in plain clothes. After a fortnight sojourn at Durban, however, an issue of kit was announced. But our hopes in this respect so long defunct, were destined to be dashed to the ground!

For in place of the complete field kit and equipment as issued to the regular soldier, and also to all the other irregular corps already raised (much as the Imperial Light Horse, Thornycrofts Mounted Infantry, Bethune Mounted Infantry, etc. etc.) all we got was - 2 suits of khaki drill (civilian pattern and of a quality usually worn by [derogatory term for local blacks deleted] a pair of blue puttees, a soft hat (colonial pattern), a pair of boots, and a military great coat. The only articles included in this trousseau which were any good at all were the boots, which were of the pattern issued to the regular soldier. No shirts, socks, or underclothing, were issued at all, and in this respect we had to put our hands in our pockets and purchase what was necessary. The great coats were all "condemned" by the ordinance Dept. as "unserviceable" and mostly bore dates of issue of many years back. The one I got for instance, was dated 1872! In addition, many of these coats were verminous and had to be fumigated. It was disgraceful that we should have been treated like this in the way of kit, especially as it transpired later, that a complete equipment [consignment] had been sent out from England for the battalion, but there had been some "dirty work" somewhere, and some other unit got the stuff instead of us.

A day or two after the first issue of kit, we were moved up by rail to Pietermaritzburg, where we lay under canvas at fort Napier the military headquarters. There, for the first time since our formation, we found ourselves encamped alongside regular troops. A battalion of the 60th Rifles occupied the adjourning lines, and the barracks of the peace garrison were also full up. In addition, fresh units were daily arriving, and being pushed up to the front. The day after our arrival, we were issued with some further equipment in the form of a full waist belt and ammunition pouch, a haversack, water bottle, and a leather bandolier for ammunition. And two days later, rifles and bayonets were given out. Obsolete Martini-Henrys (as to be expected) but brand new Lee-Enfield's of the latest army pattern!

[Put more succinctly, being a colonial volunteer regiment the ILI expected to be issued with old fashioned and obsolete Martini Henry rifles so were delighted when they were in fact issued with the very latest and modern Lee-Enfield.]

Martini-Henry rifle.

Lee-Enfield rifle.

The drills now became more interesting, since we paraded daily under arms, also, a preliminary musketry course had to be undergone, followed by a shooting test at the range. This latter, however, merely consisted of firing a few rounds at 200 and 300 yards range respectively. The standard of passing out was not high, and very few failed to qualify.

After these weeks at Pietermaritzburg the battalion was inspected by the G.O.C. at that station and pronounced as fit for duty on the line of communication.

So a week later, we were moved up the line to Estcourt, as we now entered the war zone, every N.C.O. and man was issued out with 70 rounds of ball ammunition which had to be carefully guarded, and checked daily on parade.

Before leaving Pietermaritzburg I approached an old soldier of "C" company, late of "The Bulls" who had fought in the Zulu War of 1879, on the subject of the move. His reply, however, was not exactly encouraging.

"Wait till you get there" he said "and you will be sorry you were ever born! What you have gone through here will be child's play compared with what to come!"

And so it turned out! For in addition to our battalion training, we had to perform our share of the outpost and similar duties which fall upon troops, more specifically the infantry within the theater of war. Also, we found ourselves for the first time brigaded with regular troops, and so took part two or three times a week in brigade field days. And again, there was a considerable amount of trench digging to be done, for the authorities seemed to fear another invasion of Natal by the Boers. Added to all this numerous garrison fatigues, which mostly took the form of loading and unloading stores at the army ordinance and army service corps deports, and it will be clear that our time was well occupied. However, it kept us as hard as nails, which was the main thing.

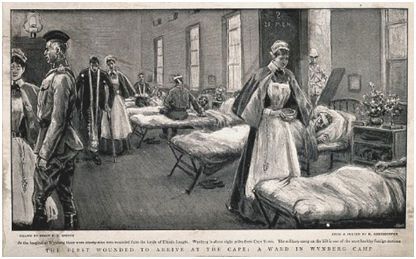

[Magazine clipping later inserted in diary]

Article text:

From "The Gunner Magazine" May 1933.

OBITUARY OF COL. CHARLES JAMES LONG, LATER OF COLENSO

COL. CHARLES JAMES LONG.

COLONEL CHARLES JAMES LONG*, late R.H.A., whose death is recorded on this page, will always be remembered in connection with the battle of Colenso, on 15th December. In order to cover the crossing of the Tugela by Barton's Fusilier Brigade, Colonel Long brought the 1st Brigade Division (14th and 66th Batteries) into action at about 1,000 yards from the enemy's position on the north bank, where, in spite of heavy shrapnel and rifle fire, they did excellent work until their ammunition was exhausted. Long was shot through the body, but would accept no attention till his wounded men had been seen to.

Had the infantry advanced under cover of his bombardment the battle might have ended differently. As it was, the only possible course was taken; the personnel retired, carrying their wounded. Seven V.C.'s were earned by parties attempting subsequently to withdraw the guns, but on the retirement of our whole force in the afternoon the Boers, who were commanded by General Louis Botha, captured them. Botha stated that Long saved the British army from walking into a trap by drawing the Boers' fire on his guns and so giving their position away.

Colonel Long had previously served in the Afghan War of 1879-80 and had commanded the Egyptian artillery in the campaigns ending with the battle of Omdurman, where their steadiness in action broke the dervish attacks and earned their commander the thanks of both Houses of Parliament and the brevet of Colonel.

Three old brother officers of the "Broken Wheel" Battery, Major-General Sir Arthur Money, Brigadier-General Cosmo Stewart and Lt.-Col. J. D. Anderson, turned out to salute their old C.O. at the funeral. Colonel Long commanded the battery, then N/2 at Weedon and Allahabad, from 1884 to 1891. He was a keen sportsman, a wonderful horse master, the staunchest of friends, and a grand upholder of all the best traditions of the Royal Regiment. R.I.P.

*Not mentioned in the obituary was Col. Long's ill-advised, some might say reckless, advancement of his artillery at the Battle of Colenso resultingin large casualties and the capture by the Boers of ten of his twelve guns. Long had commanded the British artillery at the Battle of Omdurman in the Sudan in 1898 and was highly regarded. His orders at the Battle of Colenso were however to remain in the rear and to use the Naval 12 pounders under his command, for long range work in support of Maj-Gen.Henry Hildyard's 2nd Brigade. Long's impetuosity however got the better of him and he moved his field battery to an exposed position ahead of the infantry where he was cut to shreds from concealed Boer positions.

Colenso. 10th Dec. 1899

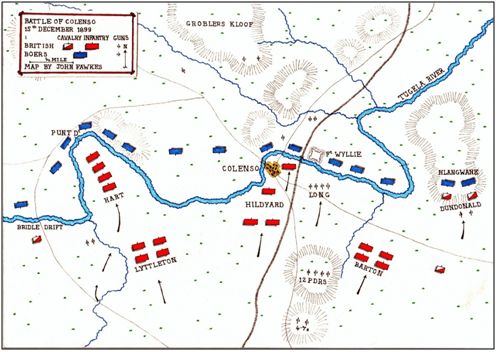

While we were at Estcourt, the disastrous battle of Colenso was fought (December 15th). A few days later, some of the infantry battalions which had been severely knocked about in the engagement, were sent down to Estcourt for rest. The men freely wandered into our lives and fraternized with us. They seemed very bitter against their officers, and probably with good reason, from their point of view. Still, even if the officers showed, as they undoubtedly did on many occasions, a lack of aptitude for leading men in the field, the fault was not so much due to want of ability, as to the defective system of military training, which had prevailed for many years past. And again, it must be borne in mind that our generals in 1899, with a very few notable exceptions, had little if any practical experience of handling large formations of troops in the field. Such experience is only to be acquired (a) by active service (b) by peace maneuvers of a large scale; in addition to the study of military history, and the strategy of great commanders. But England had not been involved in a war of any magnitude for 40 years, whilst maneuvers of any size were seldom held. Nor do any generals appear to have given much attention to the study of strategy. Had they did so, the battle of Colenso would probably never have been fought!

Map of the Battle of Colenso.

[The criticism by Jocelyn Shaw of the tactics employed by the British forces, under General Redvers Buller, VC., at the Battle of Colenso have considerable merit as it was poorly planned and executed and resulted in a retreat in disgrace and disarray. Maj-Gen Fitzroy Hart and his Irish Brigade who were supposed to cross the Tugela river at Bridle Drift got completely lost and were badly shot up, Lord Dundonald's feint on the right proved to be ineffective and Col. Charles Long was caught out in open and had ten of his twelve guns captured by the Boers.]

Now that we were in the war zone, discipline became very strict, and military offenses with relation to the enemy, such as that of a sentry sleeping on his post, were almost invariably punished by the death penalty.

Xmas passed off quietly enough, though we managed to get a good dinner including roast fowl and plum pudding. With the advent of 1900 the regular troops at Estcourt were all pushed up to the front, & by the middle of January we were the only battalion left. Being as yet only half trained, we could hardly expect to be taken into the fighting line as yet (if ever), still, we entertained hopes of at least advancing as the first line progressed.

"One of the 4.7 [naval guns] and a 12-pounder in action at the battle of Colenso."

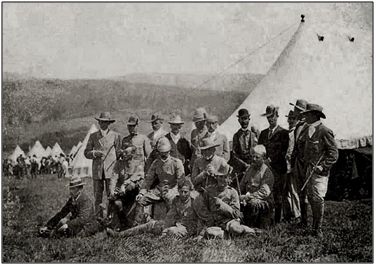

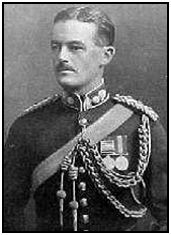

Col. William Fleetwood Nash, DSO.,

together with his ILI staff officers in the field.

He commanded the regiment throughout the Boer War and

was awarded the QSA with five clasps and the KSA with two clasps.

However, at midnight on the night 20/21 Jan. we were awakened to learn that a wire had just came through ordering the battalion up at once to the front. There was a good deal to be done. To begin with everyman's blankets had to be marked with his initials, since the blankets were all to be rolled up in bundles of 15 for each tent.

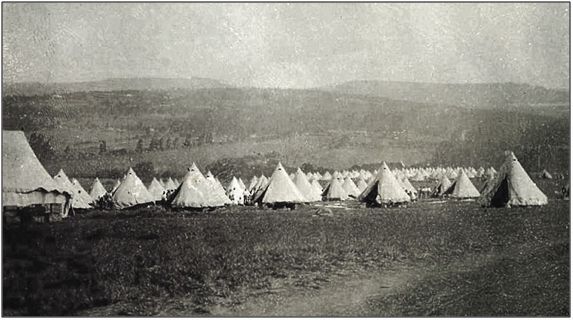

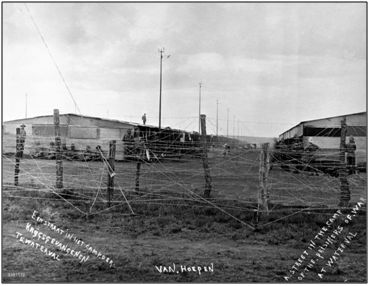

The Imperial Light Infantry in camp somewhere in the vicinity of Spion Kop.

Then the battalion transport wagons had to be assembled and loaded up with bedding, waterproof sheets, ammunition, rations, camp kettle etc. Such luxuries as tents were for now to be dispensed with and the camp was left standing, for some new unit to occupy.

About 2.0 pm on the 22nd, we paraded in full marching order, and headed by the band of the Royal Dublin Fusiliers,* marched to the railway station. We only took with us in the way of clothing and equipment what could actually be carried at the person. Every man, however, was supposed to carry a spare pair of socks in his haversack, and in the pockets of the great coat, the woollen jersey and cap comforter.

*Little would Jocelyn Shaw have known that amongst the ranks of the Royal Dublin Fusiliers was his 1st cousin, Sir Frederick William Shaw, DSO., 1858-1927. Anglo Boer War.com website. "He served in the South African War, 1900-2; as Station Commandant, afterwards Commandant, Barkly West; Station Staff Officer and Commandant, Warrenton. He was in command of the 5th Battalion Royal Dublin Fusiliers, May and June 1901. Operations in the Transvaal and Orange River Colony, January to 31 May 1902; operations in Cape Colony, 30 November 1900 to January 1902. He was mentioned in Despatches [London Gazette, 10 September 1901]; received the Queen's and the King's Medals with five clasps, and was created a Companion of the Distinguished Service Order [London Gazette, 27 September 1901]: "Sir Frederick William Shaw, Baronet, Major, 5th Battalion Royal Dublin Fusiliers. In recognition of services during operations in South Africa".

,

,

A train of open trucks was standing in the station, and in a few minutes we were all aboard. We had scarcely settled down, however, before the bugle sounded the "Fall in," and we were bundled out onto the platform again. We had, it transpired, been put into the wrong train, a brilliant piece of work, and typical of the staff! The slight error rectified, we were soon under way. A short run of seven miles [more like 14 miles]brought us to Frere, where we disembarked; thence, a march of the same length landed us at Springfield, [later re-named Winterton] where we were to bivouac for the night.

Google Map of the Spion Kop area

Next morning (the 23rd) we paraded before daybreak, being warned to expect a long march of 16 or 17 miles. This being the case it might have reasonably been expected that at least a cup of coffee and a biscuit would have been served out before morning off. But we got neither bite nor cup until the end of the march! Also the day was intensely hot. Still, our hard condition stood us well, and very few fell out. [It was mid-summer at the time with temperatures getting up into the mid-35°C range.]

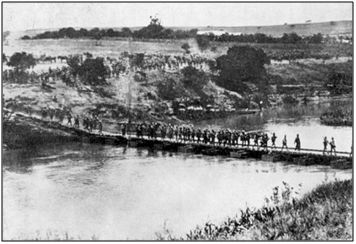

We halted on the near bank of the broad river spanned by a bridge, and as soon as dismissed the majority went down to bathe while the dinners were being prepared. After a satisfying meal, the rest of the day was mostly given up to sleep. Before starting off next morning, an additional 50 rounds of ball ammunition per man was issued. This was carried, partly in the bandolier, the remainder in the haversack.

The next day's (and last) march was about ten miles. The country, which so far had been flat and open, now became undulating, with low hills and ravines. We were now entering the lower slopes of the Drakensberg Mts. About 4.0 pm, the Tugela River was reached which was crossed by a pontoon bridge. From here, a staff officer conducted us to our bivouac, which lay at the foot of a steep and rocky ridge. Occasional artillery firing could be heard, and a good many wounded were being brought down the hill. We gathered from the Tommies we spoke to, that desultory fighting had been going on for some days, but without any definite results on either side.

The pontoon bridge.

We now learnt that we formed part of the 10th Infantry Brigade, of the 5th Division. Major General Yalbot Coke, was Brigade Commander, with General Sir Charles Warren, [left] as Divisional Commander. It was also gathered, that the formidable looking position held by the Boers in our immediate front was known as Spion Kop or Spitz Kop, & that it was intended to assault it that night. Orders now arrived for the battalion to parade at midnight, and to support the attack.

Major General Yalbot Coke, Brigade Commander and General Sir Charles Warren, Divisional Commander

And whilst on the subject of artillery, it must be noted as a regrettable fact that so little attention was paid to the gunnery training in our service prior to 1899. "Turnout" and "Spit and Polish" were everything, and a battery commander who bought (out of his own pocket) Brunswick Black to stain his horse collar (a fact which frequently occurred) was though more of than a man who was careless of such matters, but a sound and reliable gunner! And so it is an unpleasant fact to have to admit but is at the same time gospel truth, that at the battle of Spion Kop our gunners, by the inaccuracy of their fire did far more damage to our front line of infantry than to the Boers! [Transcribers Note: This is not mentioned in the Wikipedia page about the battle or in the book, The Boer War, by Thomas Packenham. It is however well documented that the Boers had a number of well-positioned and concealed gun emplacements from which they enfiladed the British trenches and positions.]

Brunswick Black.

But to resume. As the day advanced, the Boer line increased, and wounded began to be brought down in alarming numbers. The Imperial Bearer Corps [IBC] (or "the catch em alivors" as they were termed) a formation raised out of Uitlanders unsuitable for the combatant arms, were doing splendid work in this respect and largely reinforcing the greatly overworked R.A.M.C.[Royal Army Medical Corps.

IBC badge.

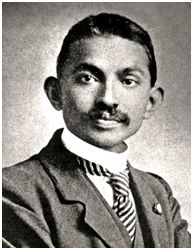

A little known fact of the Boer War was that Mahatma Ghandi served at Spion Kop with the Imperial Bearer Corps. Extract from Boer War website, "Mahatma Ghandi was involved with this corps as were many of the local Indian community of Natal who felt that they wished to contribute something towards the war effort. Their main responsibility was getting casualties from the battlefield to the field hospitals."]

Mahatma Ghandi.

It must have been about 11:0 AM that a stall officer suddenly appeared in our front, as we stood awaiting orders. He had lost his helmet, and was bleeding from a slight wound in the head. In his hand he held a slip of paper, and called for our C.O. at this moment, there were only three companies of us present, the other five companies under the colonel having been detached somewhere a short time before. So the captain of "C" company, as the senior officer present, stepped forward.

"The orders are", went on the officer, as he handed Captain X – the paper "that the Imperial Light Infantry are to reinforce the Dorsets" and he proceeded to indicate the general direction of advance adding that we should find the Dorset battalion in position at the summit of the hills on the right. Now this movement (as subsequently transpired) was about the very worst that could have been ordered under the circumstances! However, in obedience to orders, we commenced the laborious assent [sic] of the mountain, which took a considerable time, owing to the steepness and the constant necessity for halting to take cover behind a huge bolder from the heavy fire. However, the top was gained at last, and here, a most deplorable situation came to light.

Trench photograph Spion Kop.

Five British battalions were wedged into a small and narrow plateau, of a frontage and depth barely big enough to hold one battalion! And again, the position held by the forming line was not even the actual summit (as supposed), since the ground sloped gently upwards for about 60 years in our front terminating in a line of boulders, which was held by the Boer front line and greatly to their advantage, being quite concealed from view, or fire, or our firing line!

In addition to the heavy and effective rifle firing from the front, at short range our position was being successfully shelled by the Boers guns, posted on both flanks, which maintained a heavy and murderous arms & enfilade fire, and also, a howitzer in position on the lower slopes of the enemy side of the hill, was making excellent practice. Meanwhile, our own artillery, as already explained, were adding to the troubles by bursting their shells mostly over us in preference to the enemy. The arrival of still more reinforcements, in the form of the other five companies G.LG, & of Thorneycroft's Mountain Infantry (on foot), only tended to still further swell the congestion at the already overcrowded plateau. [Colonel Alexander Thornicroft, officer commanding the Mounted Infantry was one of the heroes of the day who miraculously survived the Boer hail of bullets, refusing to surrender under any circumstances and rallying his troops to continue the fight.] The men lay in the hastily improvised so called trenches literally packed like sardines in a box. For my part, all I could do was to lie down flat as possible clear behind the firing line, and hope for the best. Personally, I never once fired my rifle firstly because I could not see anything to fire at, and secondly, because to have done so would have been dangerous to our men in my immediate front.

Colonel Alexander Thornicroft.

The following extract on the involvement of the Imperial Light Infantry in the Battle of Spion Kop is taken from the website, Boer War.com

"This corps was raised in Natal and was largely recruited from those who had lost their employment through the outbreak of hostilities. The command was given to Lieutenant Colonel Nash (Border Regiment). By the end of December 1899 the regiment was ready for active service, and it was inspected by General Sir C Warren on 2nd January 1900. When the move by Potgieter's and Trichard's Drifts was projected, this regiment and the Somersetshire Light Infantry were put into General Coke's 10th Brigade, taking the place of the 1st Yorkshire Regiment and the 2nd Warwickshire, both of which had been dropped at Cape Town. The Imperial Light Infantry saw comparatively little training and no fighting until they were thrown into the awful combat on Spion Kop on 24th January 1900. The Imperial Light Infantry, about 1000 strong, was paraded at 10 pm on 23rd January, and, as ordered, they took up positions from which they could reinforce General Woodgate, who commanded the force detailed to capture the hill and was himself killed during the battle.

General Woodgate.

Sir C Warren requested that 2 companies [including Jocelyn Shaw] of the ILI be sent forward to a specified point to be ready to escort the battery to the summit. The companies of Captains Champney and Smith moved out at 6 am and waited as ordered for the battery, but about 9 am a staff-officer told them to reinforce immediately on the summit. The 2 companies advanced and reached the top shortly after 10 am. At this hour the enemy's fire was appalling, the hail of bullets and shells being ceaseless, but these untried volunteers are said to have pushed up to the shallow trench and the firing-line beyond it without flinching. They at once commenced to suffer very severe losses. These 2 companies were the first reinforcements to enter the firing-line, and their arrival proved most opportune, some Lancashire companies being very hard pressed at this time and at this part of the position.

At about 10 o'clock that night the ILI were ordered off the hill and were well advanced in their withdrawal when they were told that a mistake had been made, and the column was 'about turned' and marched back to the place they had come from, put out pickets, and lay down among the dead and wounded. The worst feature of this very trying experience was the ceaseless crying of the wounded for water: there was none on the hill. During the night a staff-officer informed Colonel Nash that he had better bring down his men before dawn if no fresh troops or orders came up. Between 3 am and 4 am the regiment was again collected and finally left the hill.

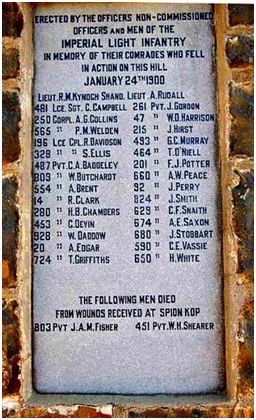

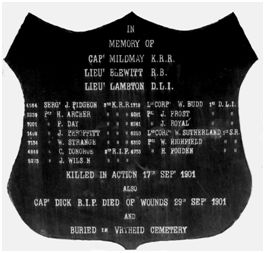

ILI Memorial inscription.

ILI Memorial.

Talking of British prisoners of war, is the famous photograph of Winston Churchill, standing, extreme right, who was admittedly a war correspondent and not a combatant, although does appear to be wearing military fatigues, taken shortly after he was captured on 15 November 1899 during a Boer attack on an armoured train on which he had managed to secure a place as an observer. The capture occurred some eighteen miles south of Ladysmith and in the immediate vicinity of the Tugela river and Spion Kop where Jocelyn Shaw was actively engaged two months later in January 1900.

POWs including Winston Churchill, far right.

We were now assembled on what appeared to be a main road, close to a small farm. After waiting for about two hours the light began to fail, and as soon as darkness set in the firing on the hill, which had been of late gradually slowing down, ceased entirely on both sides. A supper of "biltong" (a sort of dried meat greatly patronized by the Boers) and biscuit was served out, after which we were told to "doss down" where we could for the night.

Next morning, we were aroused at daybreak, and after a breakfast of coffee & bread, we formed upon the road and marched off. Our escort at first comprised about 20 mounted Boers. They were all highly jubilant, and assured us that the war would soon be over, and that they would retain their independence, and all the rest of it. During the march, the escort was augmented from time to time by Boers from other commands, all eager to learn the latest news.

About 10.0 AM, we halted at a river where we were able to indulge in a greatly needed wash. Again at midday, a second halt, where a meal of Biltong and biscuit was again issued. There again until dusk, where we were halted, and bivouacked in the open as before.

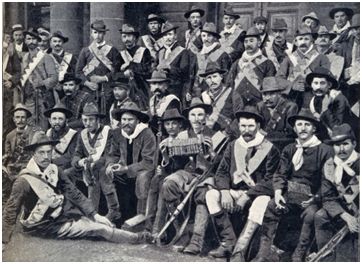

Next day's march was practically a repetition of yesterday. About 4.0 PM we arrived at a railway siding, where we found a train drawn up to receive us. But before boarding it we had to run the gauntlet of the Boer "Irish Brigade".

Irish or McBride's Brigade.

They were known as McBride's Brigade after their commander, John McBride, later executed during the 1916 "Easter Uprising" in Dublin. The brigade included many Americans and was originally organized by an Irish American, John Young Filmore Blake, (West Point Class of 1876) sitting in photo 2nd left of accordion player. The brigade comprised about 300 of whom 18 were killed in action and about 70 wounded] those traitorous Irishmen who had elected to fight for the Boers against England, under their "green flag". Their exultation at the situation was immense, and their insulting remarks far exceeded anything of the kind we had at any time to put up with from the Boers, who, with very few exceptions where kind, human, & even courteous.

The Irish Manifesto of Sept 13th 1899

"The Government of the Transvaal being now threatened with extinction by our ancient foe, England, it is the duty of Irishmen to throw in their lot with the former, and be prepared by force of arms to maintain the independence of the country that has given them a home, at the same time seizing the opportunity to strike a good and effective blow at the merciless tyrannic power that has so long held our people in bondage. The position in the Transvaal to-day is exactly similar to what it was in Ireland at the time of the Anglo-Norman invasion. The memory of the massacre of Drogheda by order of the infamous regicide Oliver Cromwell is still darkly remembered in Ireland.

England has been a vampire, and has drained Ireland's life-blood for centuries, and now her difficulty is Ireland's opportunity. The time is at hand to avenge your dead Irish. England's hands are red with blood, and her coffers filled with the spoil of Irish people, and we call upon you to rise as one man and seize upon the present glorious opportunity of retaliating upon your ancient foe. Act together and fight together. Prepare! The end is in view. The day of reckoning is at hand. Long live the republic! Irishmen to the rescue! God save Ireland!"

The train consisted of cattle trucks, and no time was lost in embarking us, a supply of rations for the journey having been issued. The railway journey to Pretoria (our destination) occupied two nights and one day, and needless to say was none too comfortable. The capital being at last reached, we found that we were finally bound for Waterval camp, 10 miles further on, on the Pietersburg line. [The Waterval camp was located at Daspoort, west of Petoria CBD on the way to Rosslyn.]

Waterval Camp

Waterval Camp.

The railway siding at Waterval Camp adjoined the encampment, and as we disembarked, and entered, we found ourselves surrounded by a surging crowd of Tommies, both regular and colonials, all eager to learn the latest news from the front.

However, we could tell them very little, except as regards our own particular show. Our names and numbers having been registered by a Boer official, we were told to seek accommodation where we could find it, and that accomplished, to report at the office to draw stores etc. The camp comprised 2 double rows of corrugated iron shelters, with a broad avenue separating them. These buildings were open to the front and so only afforded overhead cover from weather.

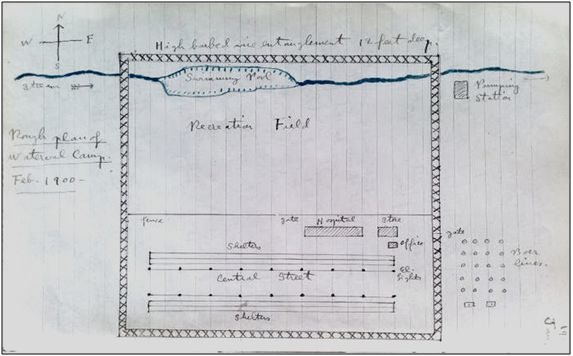

Wooden stretcher beds, and 2 blankets per man, were served out, and also a small supply of cooking utensils for each man. Beyond the rows of shelters, on the N. side was a large field for recreation. At the foot of this ran a stream, in which a dam had been made to form a swimming pool. And the whole camp was circumvented by a broad high wire entanglement, guarded by Boer sentries at short intervals.

The tents for the guards, and the officers and quarters of the stall, were just outside the entrance gate. Light was affected by electric street lamps at intervals down the center street. Having drawn our camp equipment and bedding, we were not long in finding an unoccupied quarter.

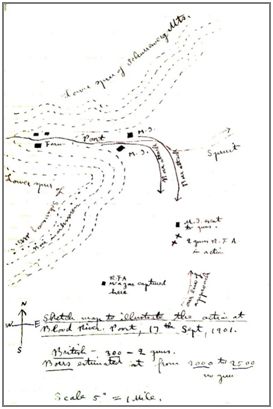

Rough Plan of Waterval Camp Feb 1900 (drawn by Jocelyn Shaw)

Scarcely had we settled in when we were summoned to the store to draw rations. These, as it turned out, amounted to,

Daily

1 lb Bread [450g]

1 lb Potatoes [450g}

Bi-weekly

1/2 lb fresh meat [250g]

Weekly

Small quantity of mealie meal, rice, sugar, salt & flour

No tea or coffee was ever issued. As a matter of fact the above scale of rations would have sufficed had they been of good quality, for we were not doing hard work. But the bread was sour and execrable, & only possible in the form of toast. The same as regards the mealie meal, which was consumed as porridge. The result of the bad feeding was much sickness in camp. The Boer government were greatly blamed at the time for it all, but as looking back it must be realized, that in Waterval Camp alone there were at one time over 4000 mouths to feed, and also a large number at Nooitgedacht, and again, that they had not too much for themselves.

A portion of plates, cups, cutlery etc, was also issued to each man. Wood for firing was drawn weekly, and in their respect the authorities showed surprising liberality, and we could take as much as we cared to carry to our quarters. However, their generosity proved false policy in the end, for towards the end of our sojourn the supply became alarmingly low, and in fact for the last week before release ceased altogether, so that many units were reduced to burning their wooden bed steads, to provide the wherewithal to cook their food.

We improvised a fireplace out of mud, which was allowed to dry until quite hard, and later on made an oven out of biscuit tin, and baked some bread with our allowance of flour, using "sour dough" in place of baking power. There was a dry canteen in the camp, where fresh milk, tea, jam, tinned fish etc. could be bought. However, the greater majority of the men came in with no money, so it wasn't much use to them! Fortunately I had some money (about £6-0-0) which the Boer did not take off me.

As we came in with just the clothes we stood up in, a modest issue of clothing was made on the day following our arrival. My share amounted to a pair of trousers 2 shirts & 2 pairs of socks. Not much, but still it all helped!

The guards comprised some 100 burghers, men either too old or too young, for service in the field. They were friendly enough and used to converse freely with us through the wire fence. They all seemed very "fed up" with the whole business and kept asking us when the war would be over.

Unfortunately, we were unable to enlighten them. The prison staff consisted of a Commandant, Assistant Commandant, Storekeeper, and Medical Officer with hospital staff. The Commandant was an excellent fellow, with a cheery word for everyone as he made his daily round of the camp. But we were less fortunate in the doctor. He was a German & seemed to know nothing whatever of his job. He did not last long, however, but was replaced by a Hollander, a much better man, who did his level best to improve matters and reduce sickness.

The sanitary arrangements left much to be desired. All refuse was deposited on to heaps which were periodically removed by sanitary carts and buried, but the stench at times was awful! All water had to be boiled before drinking. There was a good deal of dysentery and fever in camp, & funerals were of almost daily occurrence. And as for the hospital! Well, it was a place to keep out of if you possibly could!

For recreation, football was played in the big field, and camp concerts were organized from time to time in the evenings. There were a few books sets of draughts & chessmen etc. to be had. We were allowed to receive letters and newspapers, and dispatch letters, all of course strictly subject to censor. The spiritual needs of the prisoners were attended to by ministers of the various denominations from Pretoria. All church services, however, were attended by an English speaking Boer, to ensure that no official information was imparted.

The Roman Catholic, Presbyterian and Wesleyan padris [padres] did their work regularly and conscientiously, but the same cannot be said of the Church of England man, who only very rarely showed up. In the official Blue Book subsequently issued on the campaign, this individual was reported as having "regarded his personal safety to a greater extent than his duties as a clergyman" a remark not exactly tending to add to the credit of the church!

The weather was hot when we came in at the end of January, but as winter approached bitter cold winds started (it must be recollected that the altitude exceeded 5000 ft.) so we occupied ourselves in building mud walls on the outside of the shelters, to keep the night winds out.

The damp dragged on, and nearly every day a fresh batch of prisoners would arrive, either large or small. We learnt of the relief of Ladysmith, of Roberts's slow but steady progress up-country, and of the various battles fought, won, or lost, as the case might be. As regards the chances of the Boers making a final stand at Pretoria, there was much difference of opinion in the camp. The Transvaal Government, however, had for years past been constructing forts on the heights encircling the town, and now had no less than six of these works all heavily armed with the pattern of gun from Krupp. [The four main forts were Schanskop, Wonderboompoort, Klapperkop (all built by German military engineers) and Daspoortrand.] So a siege would amount to a formidable undertaking, to which the War office were well aware, and had included in the expeditionary force a mighty siege train, equipped with all the latest guns and appliances – all to be wasted however, as the Boers vacated the capital without even half an hours opposition!

[Photo of a Boer Krupp 75mm gun being positioned during the Boer War.

These guns were more than a match for any comparable artillery piece

then available anywhere in the world.]

Some few attempts at escape were made during our sojourn at Waterval, but none of them bore fruit. It was a comparatively easy matter to wriggle through the wire entanglement by night, between two sentry posts, as the sentries nearly always went to sleep, and there appeared to be no system of visiting them to test their alertness. But to cross the border into Natal (the nearest British Colony) was a different proposition altogether! The country was far too carefully patrolled to admit of this, and in every case the fugitives were brought back within a few days. The punishment was 24 hours internment in a cell, on bread and water.

About the middle of March, certain prisoners conceived the idea of constructing a tunnel under the outer wire fence, by which escape could be affected. The work commenced inside on of the shelters, by sinking a vertical shaft for a certain depth, thence a horizontal tunnel, to be shored up with timber, and continued for some distance beyond the fence, where a second shaft would afford accent to the open veldt. The work was carried out with the greatest secrecy by night, all traces being carefully covered up by day. The scheme, however, was doomed to failure, for somehow or other the staff got wind of it. The result being, that the Boers placed a machine gun 200 yds outside the camp & commanding it. [Shades of "The Great Escape" and Steve McQueen!"]

Easter came in due course, bringing a rumor of an issue of a hot cross bun on Good Friday to all hands. However it turned out to apply to sergeants & higher ranks only! As we only saw to one sergeant in our party, we all sat around him and watched him eat it. I thought he looked uncomfortable about it all, however!

De Volkstem masthead

Cronje's Surrender

The point needs to be made that the remainder of the Imperial Light Infantry, after Jocelyn Shaw and his fellow 27 prisoners were captured at Spion Kop on 24 January 1900, went on fighting in the Boer War, most notably in the relief of Ladysmith. They were not however engaged as a front line force although continued actively in the field until the end of the war.

It is astonishing how easily some people are duped! Here we had the Boers, of both the Orange Free State and South African Republic, a race of patriarchal, god-fearing, farmers, content to live on their land and earn a modest competence "by the sweat of their brow", and at the head of the state, Paul Kruger, with his gang of advisers and ministers, renegade Germans, Dutchmen, Swedes, Austrians and even Irishmen, probably the biggest scoundrels unhung in the whole globe! And all with unprecedented cunning breathing poison into the ears of the simple minded burghers, and promising them their share of the vast mineral wealth of the two countries, if only they would hang on and eject the British invader, which was bound to come about soon, since the British resources were nearly exhausted!

It is significant, however, of these same Boers, that as soon as the war was over and we took over the two states they and the British continued to live together in peace and harmony, and later, in the great war, they became our staunch allies in S. Africa, and were of the greatest assistance in the various expeditions against German aggression.

And in this manner, affairs drifted on until the end of May, when at last we began to realize that the end was not far off. The next thing we learnt was that Roberts had crossed the Vaal River, with the enemy in full retreat, and now for the first time, the Boer guards began to show signs of uneasiness. The climax came a day or two later, when we were roused from our beds at midnight, by the arrival of a number of British officers who had been interned at "The Birdcage" at Pretoria. [The Birdcage was a prisoner camp near Daspoort on the western side of Pretoria where the British officers were house in relative comfort]. Amongst these was Lord Rosslyn, [James Francis Harry St Clair-Erskine, 5th Earl Rosslyn, 1869-1939, top following page] who had come out from England as a newspaper correspondent, and whose book "Twice Captured" made a great sensation a few years later. These officers now informed us that our release was merely a question of a few days, but that we would be well advised to keep quiet and allow events to work their natural course. These same officers had been obviously sent by the Boers, who, realizing that the game was up, desired to avoid any ementé[presumably a French word meaning disruption or unrest] on the part of the 400 prisoners in Waterval. And so, excited as we were at the prospect of release. We remained calm enough, until a few mornings later when we were rewarded by the sight of a line of British Cavalry scouts, advancing on the camp. And no sooner had they appeared, than the Boer guards disappeared to a man.

James Francis Harry St Clair-Erskine,

5th Earl Rosslyn, 1869-1939

With the withdrawal of the sentries, the wire fence was trampled down, and there was a general rush to greet the new comers. And they had much news to impart. Johannesburg had been occupied without opposition, likewise the Boers had evacuated Pretoria, and dispersed to the country, to carry on (as subsequently transpired) a protracted "guerrilla" warfare.

Very soon, the remainder of the Cavalry brigade arrived. But truly a sadly depleted brigade! For each of the three regiments which had originally left Cape Town 500 strong, now barely averaged 150, owing to the wastage, in horseflesh, from disease and privation.

Meanwhile, everybody fraternized freely with the new arrivals, all eager to learn the latest. But no orders about moving from the camp were issued. At midday, we proceeded to cook and discuss our dinner, as usual. Then just as we were about to wash up, one of our men came running in screaming "There's a fight going on outside" and sure enough, the unmistakable "whizz" of a shell passing overhead, confirmed his statement! In fact, the Boers were shelling the camp!

To the best of my belief (though I may be wrong) there is no similar experience in Military History of unarmed prisoners-of-war being subjected to such treatment! But with all due justice to the burghers, it must be borne in mind that the personnel of the Transvaal State Artillery were European to a man. German, Austrian, Dutchmen, Swedes, Russian etc. were all accepted for this service, but none of Boer or even Africander [sic] birth. The reason being, that being a highly trained & scientific corps, a high standard of education was required.

It did not take us long to pack up our few belongings, or rather as many of them as we could carry, and swarm out across the veldt, there being now nothing to stop our progress. The Boer battery kept up the shelling, but the shooting was poor, the shells bursting far ahead of us, without any casualties. Also, a British Horse artillery battery soon came into action in reply to the Boer guns, and speedily silenced the latter.

After we had proceeded some half mile or so across the veldt, a Cavalry Officer appeared and assumed charge of us, changing our general direction to the left after another mile. Very soon we struck the railway line, where a train was waiting to take us to Pretoria. However, as there were 400 of us, we naturally had to wait our turn, the train returning empty each time after having dropped its cargo.

The journey to the capital did not take more than half an hour. On arrival, we found ourselves relegated to the race course where we were to bivouac for the night!

At first light, it was a distinct relief to have gained our freedom. But it speedily became clear that we were only "out of the frying pan into the fire." It was now mid-winter in the Transvaal, and although the days were bright and sunny, the nights were bitter, with a keen wind. Many of the prisoners had not even brought one blanket with them in their haste to escape from Waterval under artillery fire, and very few had brought two. (Personally I had brought one blanket, being as much as I considered I could carry, in addition to the rest of my kit). There was no scarcity of firewood, and so huge camp fires were kept going all night. But even with this aid, the cold was indescribably intense, and I, with others, spent the best part of each night in pacing up-and-down to endeavor to keep warm, making up for it all by sleeping in the daytime. Also, the rations were extremely scanty.

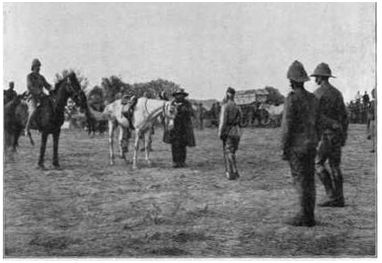

Next morning, we witnessed the entry into Victoria of the British Expedit-ionary Force under Lord Roberts. The Boers had now all cleared off to guerrilla warfare, so the entry was unopposed.[Drawing, below, of British troops on the march, the ultimate objective being Kruger's heartland, Church Square, Pretoria]. The troops, considering the hardships they had undergone, looked fit and well, and marched sturdily, more especially the Brigade of Guards.

[Drawing, of British troops on the march

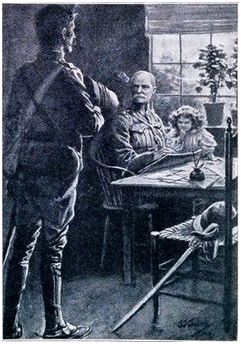

The two postcards, above, respectfully collected by Jocelyn Shaw and inserted into his diary

were typical of the esteem in which military leaders were held in their day.

The one on the right is headed, "Can't you see I'm busy ", showing Roberts working with a young child.

It does not get any more soppy sentimental than that.

Pretoria. June 1

The following morning, the whole of the returned prisoners-of-war were paraded for inspection by Lord Roberts. The Commander-in-chief did not keep us long on parade, and the only remark I overheard him make, as he rode down the line, was to the effect that we did not look up to much in the way of work.

The same day, the court of inquiry on all returned prisoners of war, as required by the Queens regulations, opened at Pretoria. We were all marched down by batches to be questioned as to the circumstances attending the capture. However, for obvious reasons, the surrender at Spion Kop was not too closely inquired into. Only one man of the I.L.I. party was called in before the court to give evidence, and he was the old soldier, formerly in The Buffs, and whom I have already alluded to and he was only asked one question.

"Do you consider" asked the President of the Court "that the circumstances justified a surrender to the enemy of your party?"

"Yes" was the reply "There was no other alternative, owing to the enemy fire being so heavy".

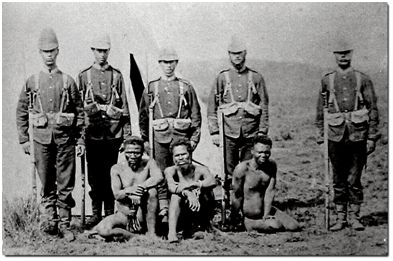

[The old soldier quoted above was previously mentioned as having fought in the British Zulu War of 1879/80.“The Buffs”, officially the East Kent Regiment trace their founding back to the reign of Queen Elizabeth I. They have a rich list of battle honours including Zululand which must have provided the old soldier with an authoritative and respected voice. Below is a photo of members of The Buffs regiment with a number of Zulu captives taken in 1880.]

Members of The Buffs regiment with a number of Zulu captives taken in 1880

And so the point at issue, as to whether we should, or should not draw pay for the period of our long internment, was settled once and for all, and satisfactorily. Also our surrender was judged as quite justified, under the circumstances. We spent five miserable days, and still more miserable nights, at the Racecourse, during which period the majority of the regular ex-prisoners-of-war were drafted off to their regiments. On the sixth day, those left of us were transferred to "The Birdcage" which had been used as a prison camp of officers, up to the date of Robert’s entry into the capital. Here at least, we were warm at night, being housed in wooden buildings. The rations however, were still scanty, but then it must be recollected that there was but a single line of railway communicating with the base at Cape Town, and that supply trains were daily being captured by the enemy. So with so many thousands of mouths to feed, the supply problem became a difficult one.

After a few days at "The Birdcage", candidates were called for the newly formed Pretoria "Foot Police" from the Colonial returned prisoners of war. Most of the I.L.I. responded, and were accepted. I personally did not, however, as I considered it important to rejoin my regiment as soon as possible, take my discharge, and get back to my job in Johannesburg as soon as possible. To enter on a fresh engagement, and thus bind myself down for a further term of service, might have been fatal.

Klip River. 1900 June – July

We Colonial details were now very much reduced in number, and of the I.L.I. there were only five of us left. However, the authorities did not seem to be in any great hurry to dispose of us. But one Sunday afternoon about a week later, the "fall in" was suddenly sounded, rifles, bayonets and ammunition, were issued, and we were warned to parade at 6:0 pm to depart for an "unknown destination". At the appointed hour we fell in, and to the number of some 200, marched to the railway station and were packed into a train of open trucks, which we found awaiting us.

No time was lost getting under way. After some four hours or so of the traveling, with frequent checks, we arrived at a station where we were ordered to disembark. Here we were allotted to certain trenches, being briefly told that an attack was expected at daybreak and that we must be prepared to meet it!

We waited expectantly through the night, and well into dawn, but nothing happened. At 8:0 am, the order "Stand down" was passed around. Having drawn rations, we occupied ourselves first in preparing breakfast, and that meal consumed, in ascertaining the situation. The station turned out to be Klip River, some few miles south of Johannesburg, on the Cape railway. At this time it was an advanced supply depot and garrisoned by one company of the Royal Irish Rifles.

During the day, the whole of the colonial details were paraded, and all except us five of the Imperial Light Infantry, packed off down country by the first train, the reason being, that they all belonged to mounted corps, and were required for mounted infantry work. We, however, were given to understand that we were to remain where we were for the present, until arrangements could be made to send us back to our regiment, which was then in Northern Natal, somewhere in the Newcastle district.

A "dug-out" cut out of the side of a bank of sand, was allotted to us as quarters, and here we continued to make ourselves fairly snug, though much worried at first by a colony of rats, who not only ran over us at night but made furious inroads on our scanty rations as well. So at last having procured some picks and shovels, we proceeded to dig up the sandbank, and in due course exterminated the whole family, both young and old. After which, we were no longer troubled.