The South African

The South AfricanOriginally published in the Journal of the Royal Signals Institution, vol.27, Spring 2008, pp. 42 - 53. Published on the Website of the South African Military History Society in the interest of research into military history

Copyright Dr Brian Austin 2008.

Ian Smith's Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI), in November 1965, undoubtedly set Rhodesia on course for confrontation. Rampant African nationalism had begun to emerge across parts of the continent in the 1950s and really took wing in 1957 when the Gold Coast became Ghana. It was soon to be followed by Nigeria in 1960 while on the east coast, Kenya, though still recovering after the Mau Mau insurrection, moved to independence in 1963. Clearly, and certainly audibly, Harold Macmillan's "winds of change" that chilled the South African parliament, when he addressed it in 1960, were already beginning to blow fiercely further north. And immediately to the north of apartheid South Africa was the Central African Federation, that grouping of the three British colonies of Northern and Southern Rhodesia and Nyasaland into a single federal unit with its capital in Salisbury (now Harare), in Southern Rhodesia. But the Federation was under strain almost from the outset when the surge towards independence in Africa soon became unstoppable as no fewer than 27 former colonies attained their independence from their colonial masters between 1957 and 1964.

Almost inevitably in that climate, the Federation fractured. In 1964, Northern Rhodesia became the independent state of Zambia while Nyasaland was renamed Malawi. But Southern Rhodesia was different. Since 1923 the colony had actually enjoyed quasi-dominion status within the British Empire, similar to that of New Zealand at the time, and to all intents and purposes it was self-governing with Britain having responsibility only for matters relating to foreign affairs. Its economy was sound and its record of responsible government was second-to-none but since that government rested in the hands of the white minority (some 225 000 whites out of a total population of about 3 million) independence on that basis was unacceptable to the African nationalist movements and to the Afro-Asian bloc at the United nations and, equally, within the Commonwealth. And this was despite the fact that the 1961 Southern Rhodesian Constitution, based on a non-racial franchise and agreed by parliament at Westminster, guaranteed majority rule irrespective of race, colour or creed. But for all that, and repeated British assurances that Southern Rhodesia would be granted independence, it all came to nought.

In 1965 Ian Smith, elected Prime Minister the year before by his Rhodesian Front Party after drawn-out negotiations with Britain had got nowhere, took the fateful decision unilaterally to declare Rhodesia, as the country was now known, independent of Britain. His country was now on its own.

At the time of UDI the Rhodesian Army numbered around 3400 regulars and

8400 territorial troops. The Air Force had about 1000 men and 100

aircraft. The manpower figures were soon to increase substantially as

peacetime soldiering turned rapidly to counter-terrorist operations and

then almost to outright war.

The oldest regiment in the army was the Rhodesian African Rifles (RAR),

formed in 1916 as the Rhodesian Native Regiment. It had a distinguished

fighting record beginning in Tanganyika during the First World War and

continuing, as the RAR, in Burma during the Second World War and again

in Malaya in the mid-fifties. The Rhodesian Light Infantry (RLI) was

formed in 1961 as one of five battalions of the Federal Army. Unlike the

RAR with its black troops and NCOs under the command of white officers,

the RLI was an exclusively white unit reflecting the concerns then

emerging in Southern Rhodesia as the former Belgian Congo burst into

flames and the Federation's own foundations began to crumble. At around

the same time an armoured car squadron (equipped with Ferrets) was

formed, as well as a paratroop squadron, essentially a resuscitation of

the Rhodesian C Squadron, Special Air Service (SAS) that had also

operated in Malaya. All were served by

the Rhodesian Staff Corps of some 47 officers and men with its HQ in

Salisbury and amongst whom was 1 Commander Signal Squadron.

The Southern Rhodesian Signal Corps was gazetted in 1948 and affiliated

to the Royal Corps of Signals a year later. Its predecessor was the No 1

Signal Company, numbering some 50 men, almost all of whom had been

recruited from the Southern Rhodesian Posts and Telegraphs Service soon

after the outbreak of the Second World War. They soon found themselves

with numerous other Rhodesians fighting alongside British and other

Commonwealth troops in the Western Desert. Rhodesia's contribution to

the war effort was some 26 000 troops, of whom 15 000 were Africans and 1

500 were women. It was said to have been the largest contingent per

head of population from any country in the Empire.

Fig 1 The Rhodesian Army Signals Corp Jimmy

With the setting up of the Central African Federation in 1953 many

changes occurred within the military establishment tables. The Rhodesia

and Nyasaland Corps of Signals (RN Sigs) came into being in February

1957, though 1 Commander Signal Squadron had been in existence before

then and continued thereafter. The first Staff Officer Signals at Army

HQ in 1953 was Major D H Grainger. In 1957, Lieutenant Colonel Grainger

OBE, ED, became the first Director of RN Sigs and served in that post

until 1963. As a colonel, he then commanded 3 Brigade on its formation

in 1967 before retiring to become the first (and only) Honorary Colonel

of RhSigs until 1971.

The pool of Signals talent in Rhodesia was to be increased significantly

during those early years as a result of the influx of a number of

experienced officers and NCOs from the South African Corps of Signals

(SACS). This occurred following the defeat in the general election of

1948 of Field Marshal Smuts's United Party government in South Africa by

the Nationalists who had attempted, by both fair means and foul, to

keep South Africa out of the war - especially if that meant being on the

side of Britain! Memories of the Boer War were both long and bitter. Dr

DF Malan's National Party government soon lost no time in purging the

Union Defence Force (UDF) of senior officers who were perceived to be

"too British" in philosophy and outlook. In their place came men whose

sympathies were much more in line with those of the new government.

Many, of course, had seen little or even no wartime service. The rapid

promotion of officers for reasons of their political compliance rather

than their military credentials was soon evident even at much lower

levels within the rank structure and many English-speaking officers,

seeing their careers suddenly blighted, left the UDF. The immediate

beneficiaries of this haemorrhaging of talent were the Federal Army and

Air Force across the Limpopo River to the north. As a result, by 1960,

some 40 per cent of the European element of the Federal forces were

South Africans.

It was not just the South African military that was losing men of calibre. With the break-up of the Federation in 1963, there was no real drive to improve conditions of service and thereby to make a career in the army seem particularly attractive. Instead the financial brakes were applied after the Federation's demise and many men therefore left the colours.

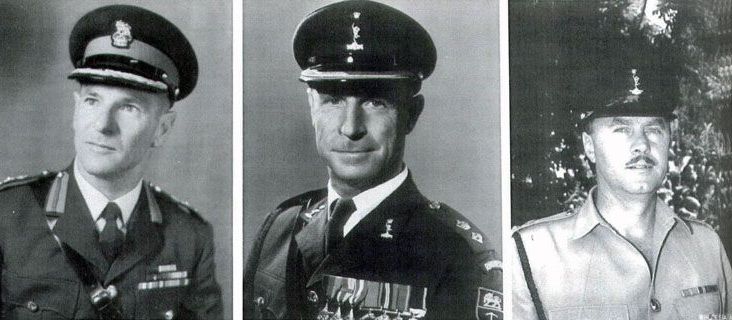

Fig 2.Colonel DHG Grainger OBE ED, Colonel and Honorary Colonel Rh Signals; Lieutenant

Colonel OD Mathews, D Sigs 1964-66; Lieutenant

Colonel WTD de Haast MBE, D Sigs 1967-70

The Director of Signals (D Sigs) at this time was Lieutenant Colonel

Denis Mathews, who had previously been OC The School of Signals of the

SACS. Mathews was faced with a number of immediate tasks: to provide

adequate fixed communications for the Army; to recruit personnel into

the Corps; to ensure that the Corps had sufficient competent instructors

as well as equipment and vehicles for its training role and for the

various squadrons, and most importantly, to replace the radio and other

equipment inherited from the Federal Army that was now both

inappropriate and chronically unserviceable.

The HF radio equipment used by the Rhodesian Corps of Signals at the

time consisted of the SR 62 at Battalion/Company level and the SR A10 at

Company/Platoon level. A note on the nomenclature is in order at this

stage. Whereas the wartime British Army radio equipment was prefixed by

WS for "wireless set", the form changed thereafter and the Rhodesian

Army used SR for "station radio". Hence the SR 62 was the former WS

No.62, developed immediately after WWII and based on those two

workhorses, the WS No.19 and WS No.22. But from here on in this account

of Rh Sigs the numbering system will deviate markedly from the British

scheme of things and even though some numbers may suggest direct

equivalence, it may no longer be the case and readers should be aware of

this fact. It is of interest, too, to note that the A10 was actually an

Australian design known there and elsewhere as the A510. The Rh Sigs

radios were therefore unique unto themselves and in many cases this was

true in many more ways than one!

For communications within infantry battalions the Army used the SR 31

and the SR 88 sets, both of which operated on FM within the 38 to 48 MHz

or "low-band" part of the VHF spectrum. But this equipment had seen

much rugged service with the Federal Army and the sets were now

notoriously unreliable. Consequently, they were well nigh useless. An

experiment, which was to prove to be a portent of an extremely important

development to come, saw the introduction in about 1962/3 of high-band

(118MHz), amplitude modulated (AM) handheld radios designated the SR

47F. They were acquired because of the need for ground-to-air

communications at platoon level but the particular sets were not

sufficiently robust and proved unreliable. However, an important "high

band" VHF application, soon to become vitally important, had been

identified.

Ever since its inception, Rh Sigs had obtained virtually all its

equipment from Britain. If for no other reason, long established ties of

loyalty to the Royal Corps of Signals and to British-manufactured

equipment in general had determined the policy. However, the Rhodesians

had no influence on its specifications or design and occasionally this

meant that equipment was in use that was not entirely appropriate for

the task in hand. In addition, there was the need to keep in stock

costly quantities of spares because of the long procurement and delivery

delays that were typical of the times. And so to circumvent these

problems there was good reason to liaise much more closely with the

rapidly developing South African armaments and electronics industries.

Ties were therefore established in the early 1960s with two companies in

Durban that were developing military radio hardware. Then, in November

1965, Rhodesia's decision to declare UDI made these South African links

absolutely obligatory because the supply of all British-made equipment

ceased abruptly.

As early as 1957, Second Lieutenant A H G Munro, when minding the shop

in the absence overseas of the Army's Staff Officer Signals (Major

Grainger), was instructed to prepare a report for the GOC's Annual CO's

Conference, including a forecast of likely developments in the

communications field. Gordon Munro, appreciating the part that

transistors were now beginning to play in electronics systems, and aware

of the importance of single-sideband (SSB) as a far more effective mode

than full carrier AM, stuck his neck out in that document and predicted

that within ten years solid-state SSB transceivers would be available

in manpack form. On his return Don Grainger gave him a rocket for

allowing his imagination to get the better of him but the young

subaltern stuck to his guns. Major Munro was to be proved right - and

almost on time too - when, in May 1967, the TR28 (or B16 in Rh Sigs

nomenclature) 25 W PEP SSB manpack appeared in the signals inventory in

Rhodesia. That equipment, the first SSB manpack in the world (which

followed its RT14 prototype), was designed and developed in Durban by

S.M.D. Electronics, soon to be Racal SMD and then Racal South Africa

when the British radio communications manufacturer became its major

shareholder. The TR 48 (SR B22), a synthesized SSB manpack, was to

follow and to become Rhodesia's stalwart for long-range, portable,

communications. Thus Racal, in its various guises in South Africa,

became a very significant source of state-of-the-art equipment for the

Rhodesian military. In fact, the first of many variants of SSB

equipment supplied to the Rh Army by S.M.D. was the SR 422B, a 100W PEP

mobile set with four crystal-controlled channels. This followed its very

successful use by the Rhodesian Department of National Parks as early

as 1961. It was known as the SR C14 by the Army where it saw long

service in logistics links. It would soon be supplanted in a frontline

role by the TR15 (SR C24), a highly effective SSB transceiver (soon to

include a frequency-hopping version) and both were designed and

manufactured by Racal South Africa.

Fig 3.School of Signals Radio Technicians ca 1970 with the School Commandant Maj NI Osmond,

front row second later D.Sigs 1971-73

Another Durban electronics company called United Electronics,

specialising mainly in VHF equipment, had stepped into the breach early

in 1965 when the SR 47s were discarded by supplying Rh Sigs with the A60

Mk1, a lightweight VHF AM transceiver with six crystal-controlled

channels in the aeronautical band. These sets were issued to 1RAR, 1RLI

and C Squadron SAS down to platoon/troop level for ground-to-air use and

they soon proved their worth when used during a major exercise (Ex LONG

DRAG) held in September 1965 just two months before Ian Smith announced

Rhodesia's unilateral declaration of independence.

The outcome of Ex LONG DRAG was to prove crucial to the subsequent modus

operandi of the Rhodesian Army and indeed to its Corps of Signals. LONG

DRAG was organised by 2 Brigade for the purpose of testing its primary

unit, the RLI, recently converted from a conventional infantry battalion

to a smaller and more mobile commando unit with significantly increased

firepower. The exercise also involved troops from the RAR, SAS,

Engineers, Service Corps as well as the Rhodesian Air Force to provide

the necessary air support, reconnaissance, casualty evacuation and so

on. It was, in fact, the largest exercise held since the break-up of the

Federation. The exercise area was very extensive too, covering the

northern and eastern regions of Rhodesia.

HQ 2 Bde functioned as higher control for the exercise with K Tp, 2 Sig

Sqn, in the field with the new C14 radios to provide the necessary

long-distance communications. A calamity that nearly brought the

exercise to an ignominious close, almost before it had begun, happened

when radio communications between the exercise area and Cranborne

Barracks in Salisbury proved to be well nigh impossible. However, the

situation was rescued when WO1 Con Stuart-Steer, commanding K Tp,

constructed and erected (in double quick time) an antenna system known

to the international radio amateur community as the G5RV. Its

multi-frequency capability, horizontally polarised pattern and high

angle of radiation at low frequencies were ideal for the sky wave

propagation paths over the distances involved in the exercise. This

proved to be a salutary lesson.

Maj Munro, now OC 2 Sig Sqn, was the Chief Technical Umpire for the

exercise and, at its conclusion he, along with two colleagues from the

Army Service Corps, had to report on all technical and logistics aspects

and this, of course, included communications. Ground-to-air

communications using the A60 Mk1 were excellent even up to distances of

150km, depending upon intervening terrain and the aircrafts' altitude,

of course. By contrast, regimental communications within 1RLI, who were

still only equipped with the SR 62 and SR A10 radios (the TR28/B16 had

not yet arrived), were generally unreliable and often poor. Again, the

day was saved by the action of an experienced regimental signals officer

who set up a relay station, equipped with the A 60 sets, on high ground

in his area of operation. As a result he achieved good 24-hour

communications for his Commando and in so doing sowed a very important

seed. Maj Munro's umpire's report made special mention of this and, in

due course, it came to the attention of the Director of Signals who,

with his staff in the Directorate, soon realised that this use of

frequencies in the aeronautical band for ground-to-ground purposes

opened the way for an integrated communications system which naturally

included the Rhodesian Air Force. But to provide for so many additional

functions made radio equipment with a multi-channel capability an

absolute necessity.

Fig 3. Lieutenant Colonel AHG Munro D Sigs 1973-76 receiving the Defence Force Medal for Meritorious Service in 1972

To those who have spent their lives as army signallers it will immediately be evident that thinking along such lines bordered on heresy because army VHF communication took place at so-called "low band" VHF (typically, 26 - 76 MHz). In addition, the allocation of radio frequencies to users - whoever and wherever they are - is a very carefully controlled and closely monitored activity, backed up by the rigours of international treaty and with the coercion of international sanctions always hanging over those who flout them. Fortunately, the relevant clauses amongst the international telecommunications regulations contained the inevitable footnote. It allowed countries in various parts of Africa to use frequencies in the aeronautical VHF band (or "high-band") for mobile ground-ground purposes provided the local frequency registration authorities agreed. In Rhodesia's case such agreement was readily forthcoming because the Department of Civil Aviation was the authority immediately concerned and it had long-since accepted the situation.

Fig 4. Lieutenant Colonel RTO Tilly, D Sigs/C Rh Sigs 1976-78 flanked by

Major General ALC Maclean, Chief of Staff, and Major HC Jaaback, C Rh Sigs 978-80.

But another hurdle had to be overcome and it had the potential of being

equally as damaging were agreement not reached. Local alliances between

some countries of southern Africa were strong: Rhodesia and South

Africa, particularly, were bound in many ways by ties of kith and kin

while both, in the late 1960s, both were facing the twin pressures of

African nationalism and negative world opinion. In addition, the two

Portuguese territories of Angola and Mozambique were in the same boat.

The natural inclination was for the military establishments in the three

countries to liaise very closely and nowhere is such cooperation more

crucial than in the area of radio communications. Both South Africa and

Portugal followed the policy of equipping their forces along Nato lines,

the latter for the obvious reason that she was a founding member of

that alliance. And standard Nato policy was to use "low band" VHF, with

frequency modulation (FM), for ground-to-ground communications within

and between armies. Any Rhodesian decision unilaterally to use "high

band" VHF, and with amplitude modulation (AM) to boot (since

aeronautical VHF communications were all conducted on AM), would cause

much concern and not a little chaos.

The Rhodesian Signals Directorate well understood all this. Fortunately

their links with their South African colleagues were very harmonious.

Following UDI and the immediate exclusion of all Rhodesians from any

contact with the British military establishment, those ties became even

stronger with contact and collaboration at all levels. Many Rhodesian

officers who would have attended Sandhurst as cadets and then returned

some years later as students on Staff Courses at Camberley, now found

themselves on such courses in South Africa instead. Indeed, possibly the

last Rhodesian to see the inside of Camberley was Major Norman Orsmond

who was destined to become Director of Signals of the Rhodesian Army. He

completed his staff course there the day before UDI was declared!

Though Ex LONG DRAG had clearly indicated the advantages to be gained by

going the "high band" route, and both the 12 channel A60 Mk2 and then

the 24 channel A63 were obtained from the manufacturer in Durban, other

factors necessitated closer liaison between the southern African allies.

By 1970 all three countries were facing either incursions by

Marxist-trained and inspired terrorists (ZANLA and ZIPRA) or, as in the

case of Mozambique, an internal insurrection by FRELIMO, the nationalist

movement bent on driving the Portuguese out of the colony.

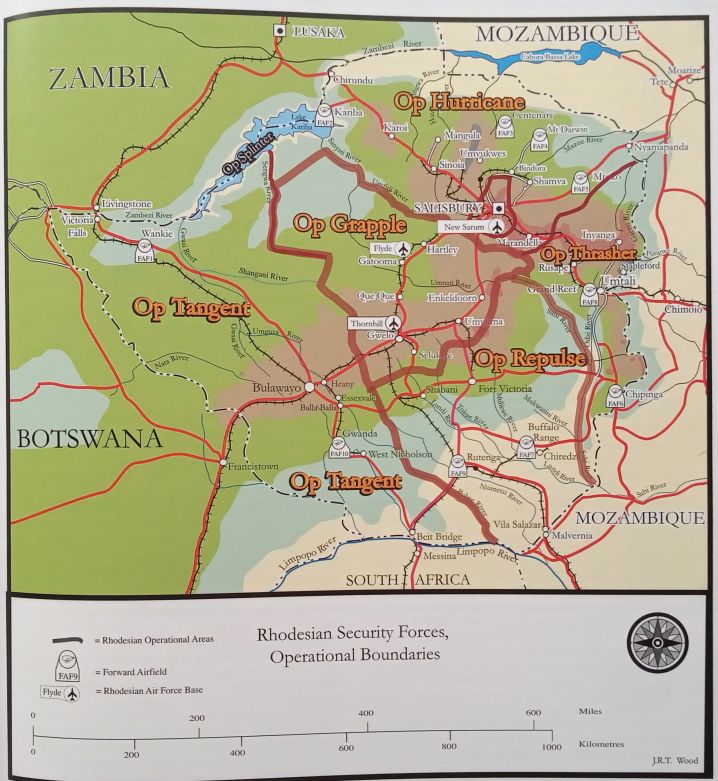

Rhodesia set up a number of operational areas as the terrorist

incursions spread across the country. Each area was given a highly

distinctive name such as Op Hurricane which extended through the north

and northeast; Op Thrasher that covered the eastern region, Op Repulse,

the southeast, and so on. Within each was the Joint Operational Command

(JOC) from where everything was coordinated. Sub-JOCs existed at the

various Forward Airfields or FAFs, while the two main air bases were at

New Sarum outside Salisbury and at Thornhill near the town of Gwelo.

Cooperation between the armed forces of (some of!) Rhodesia's neighbours

was now vitally important too. In the early days of the bush war

Rhodesian and Portuguese troops fought almost shoulder-to-shoulder in

some actions while South African troops and aircraft were to play an

ever more important role later on. This cooperation between the three

countries stepped up a gear in 1971 when agreement was reached to

standardise military communications as far as possible so as to achieve

compatibility down to the lowest level. This, of course, meant low band

VHF with FM as the modulation mode, precisely the system the Rhodesians

had abandoned five years before.

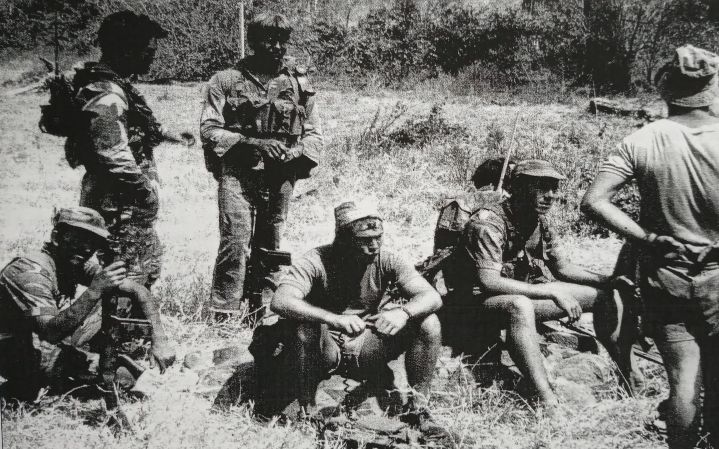

Fig 5 L Troop, 3 Brigade Squadron, 1971

To some extent Rhodesia's hands were tied because of its dependence on

the South African armaments industry. The Signals Directorate, under its

new Director Lt Col Orsmond (who had just taken over from Lt Col Bill

de Haast) and his Air Force counterpart, therefore had little option but

to agree and so the 24 channel SR A30 was ordered from South Africa for

use by the infantry. Both the Rhodesian Air Force and the para-military

British South Africa Police (BSAP), whose history was as old as

Rhodesia's itself, took steps to equip themselves accordingly in order

to ensure interoperability.

But the infantry were soon decidedly unhappy and it was the man

literally on the ground - the infantry soldier - who rejected the SR

A30. The flexible whip antenna it required at low-band VHF was too long:

it got in the way when boarding and alighting from a helicopter; it

made a noise when being dragged through the thick bush of the Rhodesian

lowveld and, most importantly of all, it made the man carrying the radio

a sitting duck of a target. These concerns were soon raised at the very

highest level and since they were echoed by the Air Force, but for

rather different reasons, they carried much weight.

The Rhodesian Air Force was greatly concerned at the switch to low-band

VHF forced upon it because of the need to maintain radio contact between

its helicopters and the troops on the ground. Until now the existing

high-band VHF equipment onboard the helicopters served this purpose

admirably. Changing to the lower frequencies would necessitate fitting

antennas more than twice as long as the existing dual dipoles mounted on

pylons ahead of the helicopter's Perspex canopy. Not only would the

increased length pose severe operational problems to the aircraft but,

even more importantly, it was felt that the Becker homing system with

which all the helicopters were fitted, and which played such a crucial

role in the operations with the army (as we shall see), would be

severely compromised.

It was clear that a critical decision had to be taken even if that meant

reversing the previous one and incurring some cost penalties as a

result. The Director of Signals to whom this unenviable task fell was Lt

Col Gordon Munro (no stranger to controversy!). After studying the

situation very carefully, and having conferred at length with his

counterparts in the Air Force and the BSAP, Gordon Munro, in his

position as ex officio chairman of the Joint Signals Board (JSB),

produced a logical and tightly argued case that he submitted to the

Operations Coordinating Committee (OCC) for its approval. It was soon

forthcoming and so the reversion to high-band VHF was approved. In the

light of the rather special circumstances in which the Rhodesians found

themselves, the South African military agreed that compatibility with

its ground forces should, under the circumstances, be sacrificed. The

Portuguese by this stage had already abandoned both Angola and

Mozambique.

Fig 6 Rhodesian Security Forces operational areas

Throughout the Bush War the Rhodesian Air Force flew, amongst many other

aircraft, the Alouette III helicopter, usually in very close support of

the RLI, RAR, SAS and Selous Scouts below them on the ground. It

became the workhorse of the war and the Fire Force tactics developed by

the Army and the Air Force depended on the very closest of cooperation

between them.

By 1970 the degree of "jointery" achieved between the Army, the Air

Force and the BSAP made the Rhodesians into a formidable fighting force

and the terrorists were very much on the back foot as a result. The

country had even managed to ride out the privations caused by

international sanctions by adapting to the circumstances and by

exploiting to the full the rich agricultural harvest that had long made

Rhodesia the breadbasket of Africa. This spirit of enterprise paid off

in other directions too with some individuals becoming expert "sanctions

busters"!

Fig 7 An Alouette III Helicopter and RLI stick during a Fire Force operation in the Zambezi valley.1979

The Fire Force concept was defined in the counter insurgency (COIN)

manual as the "Immediate reaction to a reported terrorist presence by

helicopter-mobile troops in conjunction with appropriate air support".

The Fire Force itself consisted of a reinforced rifle company of 120 men

made up of the command element, helicopter-borne "stop" groups, a

parachute "sweep" group and a reinforcement group also known as the land

tail or second wave. Its key element was the four man "stick" with each

stick (of which there were usually four or five per operation) under

the command of a corporal armed with an FN 7.62mm rifle and carrying an

SR A63 radio. With him were three infantrymen, one with a

general-purpose MAG machine gun while the others were armed with FNs.

One of those also doubled as a medic. The corporal had considerable

autonomy as to how he conducted the operation and he exercised a degree

of initiative not common at that level in many armies. As a result, it

was very much a "corporals' war". Working closely with the sticks were

tracker-combat teams of four to five men whose tracking skills had been

honed by the rangers of the National Parks Board.

Fig 8. Regrouping after a Fire Force operation

The sticks went into battle in the Alouette helicopters led by the K-car

carrying the Fire Force commander who was usually an RLI major. As well

as controlling the action on the ground by radio, the K-car also played

a vitally important attack role because it was armed with a

side-mounted 20mm cannon. Following immediately behind it were three or

four other Alouettes each armed with twin (later quad-) barrelled 0.303

calibre machine guns. Each G-car carried a four-man infantry stick.

Later in the Bush War, the RLI joined the SAS is using paratroopers

jumping from the Air Force's fleet of vintage Dakotas. The paras set up

ambush positions and stop groups as part of the Fire Force actions and

also played crucial roles in the many cross-border operations that the

Rhodesian Army mounted into both Mozambique and Zambia.

From a signals point of view it's important to understand how the Fire

Force operated. Essentially there were three distinct types of

operations: pre-emptive strikes, call outs and rapid reaction events.

The first usually followed intelligence reports from a variety of

sources, e.g. captured terrorists and collaborators, from SAS teams or

from airborne reconnaissance by the Air Force's Canberras and Hawker

Hunters. The second followed reports, by radio, from ground-based

observation posts (OPs), soon to become the preserve of the Selous

Scouts who were quite unsurpassed as clandestine operatives; while the

third would be in response to a terrorist attack on ground forces or

civilians. All Fire Force actions clearly required excellent radio

communications with the last even involving in-flight briefing by radio

when en-route. Not surprisingly, the conventional army-style voice

procedure was found to be far too pedestrian and so a very slick

procedure soon evolved that became synonymous with the Rhodesian

military forces. To increase the area of coverage relay stations were

sited on carefully selected mountains with some being unmanned and

therefore battery charging was accomplished using solar panels.

In 1976, when Lt Col Dick Tilly took over as DSigs , a title soon to

become Commander Rhodesian Corps of Signals (C Rh Sigs), the situation

in southern Africa changed dramatically. First of all, following a

military coup in Portugl in 1974 and the toppling of the government, the

two Portuguese territories in southern Africa, Angola and Mozambique,

were granted precipitate independence. The outcome was that Robert

Mugabe's ZANLA were given free rein within that country by the

Mozambique government of Samora Machel. Then, South Africa embarked on

its détente exercise of trying to reach an accommodation with the

so-called front-line states. Until then there had been a contingent of

South African policeman operating alongside the Rhodesian forces,

ostensibly to prevent South African terrorists from infiltrating through

Rhodesia en route to South Africa. They were now withdrawn and

Rhodesia, essentially, was on its own.

Then, in September 1976, the Americans became involved when Henry

Kissinger, the US Secretary of State. He contrived with the South

African government to put pressure on Rhodesia to reach an immediate

accord with the African nationalists led by Mugabe and Nkomo. But to the

Rhodesians that looked like abject surrender and it was made worse by

the fact that the South African government had taken steps to hold back

essential supplies of ammunition and fuel that were so vital to

Rhodesia's military success in the field. In addition, South African

helicopters and their crews, as well as members of the South African

Corps of Signals who had been engaged in electronic warfare (EW) on

Rhodesia's northern border, were summarily withdrawn. But all was far

from lost, at least from a Signals point of view. In 1975, a Rhodesian

company well known as a manufacturer of domestic and car radio receivers

began producing equipment suitable for the much harsher military

conditions. WRS Electronics, having obtained the services of a highly

skilled engineer from South Africa, produced a synthesized AM

transceiver that operated from 122 to 142 MHz that became the SR A76 in

the Rh Sigs inventory. It followed this with synthesized HF SSB radios

SR B29/30, the latter with an automatic antenna tuning unit (ATU).

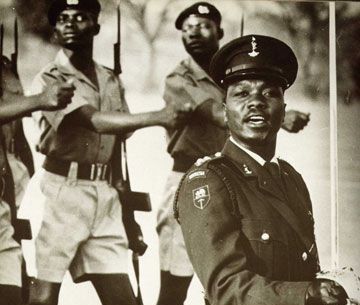

Fig 9 Lt Fana Takawira Ndluvu, Rh Sigs, and a bunch or recuits at the RAR depot

The intensity of the bush war increased markedly and the Rhodesian

forces were, at times, considerably stretched. In March 1977 Rhodesia

appointed a Commander of Combined Operations (Lt General Peter Walls,

formerly Commander of the Army) and a Combined Operations Centre

(Comops), with Lt Col Henton Jaaback, who was soon to become C Rh Sigs,

as Senior Signals Officer. Comops now took overall charge of the

execution of the war, both tactically and, to some extent,

strategically. The enemy was no longer the rather rag-tag bunch they

were in 1966 when the first serious raids were launched into Rhodesia

from Zambia. By 1978 the Chinese-backed ZANLA forces of Mugabe claimed

to have 15,000 armed men inside Rhodesia; by comparison Nkomo's ZIPRA,

with its Russian backing, never deployed more than 2,000 inside the

country. The bulk of ZANLA's forces remained in Zambia. This disparity

in approach was just one of many differences between the two terrorist

"armies": ZIPRA were essentially trained for a conventional assault on

Rhodesia when the time was judged to be right; ZANLA, by contrast,

adopted Mao's doctrine of infiltrating the local population who were

then to be cowered, often with considerable coercion, into furthering

Mugabe's cause. However, a tenuous and often extremely fractious fusion

between the two terrorist forces was eventually brought about by

pressure from the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) and so the

so-called Patriot Front (PF) came to be ranged against Rhodesia's

military forces.

To counter this the Rhodesians mounted a series of cross-border

operations to destroy the PF camps that intelligence had indicated were

bases from which incursions were being mounted into Rhodesia. Accounts

of these highly successful raids have been given in considerable detail

elsewhere, so just one will be discussed here, but it should be

appreciated that Rh Sigs played a massively important part in all of

them since their success depended critically on effective radio

communications. The fact that communications were so successful meant

that Signals were frequently just taken for granted. Not only had the

Fire Force tactics become highly developed but also the more

conventional style of warfare involving much larger forces, including

Rhodesia's Armoured Car Squadron as well as the Rhodesian Artillery, was

becoming increasingly common.

Op Uric in September 1979 was a classic example of a highly coordinated

cross-border raid by Rhodesian land and air forces supported by a

significant number of South African Air Force helicopters and ground

troops (the South African government under its new Prime Minister, P W

Botha, being considerably better disposed towards the Rhodesian cause

than was his predecessor B J Vorster). Since it was known that FRELIMO,

now essentially the army of Mozambique, were equipped with Russian-made

radars, the Rhodesians fitted a Dakota aircraft with HF, VHF and UHF

receivers connected to clusters of antennas disposed about the Dakota's

fuselage. That appearance led naturally to its name, the Warthog. The

four signallers from 8 Sig Sqn, the Army's EW specialists, who manned

the Warthog were able to monitor all possible frequencies likely to be

used both by the radars as well as the usual communications channels

used by ZANLA and ZIPRA. Also on board was a Rhodesian-developed

automatic encryption system connected to the signallers' teleprinters

thereby massively speeding up the processing of all outbound radio

messages. This unarmed EW aircraft was to prove vital in all such

cross-border operations and it contributed greatly to their success.

Though the Rhodesians were never defeated on the battlefield, such conflicts as the country had waged for nearly fifteen years since UDI are never won by military means alone. Eventually, in November 1979, the Lancaster House Conference settled Rhodesia's fate. The following February the country went to the polls and Robert Mugabe's party won a landslide victory - though evidence of massive intimidation was stark. In a letter to The Times in January 1978, the retired British General Sir Walter Walker wrote the following about the Rhodesian army:

"Their army cannot be defeated in the field either by terrorists or even a much more sophisticated enemy. In my professional judgement based on more than twenty years' experience, from Lieutenant to General, of counter-insurgency and guerrilla type operations, there is no doubt that Rhodesia now has the most battle-worthy and professional army in the world today for this type of warfare."

And undoubtedly, Certa Cito meant exactly what it said in Rhodesia.

The author gratefully acknowledges all the assistance and encouragement he received when writing this article from two retired Directors of Signals of the Rhodesian Army, Colonel Gordon Munro and Brigadier Norman Orsmond. The former's history of Rh Sigs (co-authored with Lt Col Henton Jaaback) is an invaluable reference from which many of the photographs and tables used here originate. The author also wishes to place on record his sincere thanks to Chris Cocks of the publishers 30 Degrees South in Johannesburg for permission to use photographs and other material from "The Saints" by Alexandre Binda and to Richard Wood for use of the map.

Brian Austin is a retired academic and sometime soldier. As an

electronics engineer educated in South Africa he worked for ten years in

the Chamber of Mines Research Laboratories developing radio systems for

use underground in mines before becoming a senior lecturer at his alma

mater, the University of the Witwatersrand, in Johannesburg. Then, after

emigrating to England with his family in 1987, he joined the Department

of Electrical Engineering and Electronics at the University of

Liverpool.

His soldiering all took place in South Africa where, after national

service in the South African Corps of Signals, he spent another twelve

years in the Citizen Force (TA equivalent) before retiring as OC

Tactical Communication Signals Squadron at Witwatersrand Command in the

rank of Major.