The South African

The South African

Published on the Website of the South African Military History Society in the interest of research into military history

Copyright Desi Halse 2010.

On returning to South Africa, Roy Halse writes of his wartime experiences, his capture while fighting in the North African desert during World War Two, his imprisonment, and his escape from the camp in Italy.

(After Tobruk fell in June 1942, Rommel and the Afrika Corps advanced Eastwards through the desert until they engaged the Allies in November at the battle of El Alamein, where they were defeated.)

'After twelve months, and for some, double that period, we had been fighting up and down the Libyan desert.

We arrived in Tobruk tired and weary, most of us rather glad that we had reached that sanctuary after a very fierce and lively spell. But four days later, Tobruk fell....

Will I ever forget Sunday 21st June 1942? Rommel demanded the surrender of Tobruk at 7a.m. having smashed through the Eastern Perimeter and captured the harbour at 4p.m. on Saturday.

The first information we got that everything was lost was at 8.30a.m. Orders went round to burn and destroy all vehicles, equipment and arms. Hundreds of armoured cars and vehicles were driven up and over cliffs, the drivers jumping clear, and allowing the cars to continue, finally disappearing into the sea. Thousands of vehicles were strewn with petrol and set alight...mobile workshops, ammunition trucks, anti-tank portes* and service trucks all went up in smoke. Guns and ammo. were destroyed. By ten o'clock one could hardly see anything of Tobruk for smoke and petrol-drums and tanks blowing up. One would have thought the battle was still raging.

[*portes: MILITARY gun hole : a small opening in an armoured vehicle or fortification through which a gun can be fired]

We were terribly dazed and depressed. Everything seemed like a bad dream. Most of us helped ourselves to cigarettes and beer from the canteen wagon and also from another quarter store. Even the natives managed to get some beer and cigs. Before we could destroy our canteen wagon, Germans in armoured cars arrived, and ordered us to 'Hands up!' The Germans systematically rounded us up with despatch and cold efficiency. We marched in groups for about fifteen miles, arriving at Tobruk harbour. We had walked from near the Western perimeter. The German soldier who was in command of some two thousand or more of us called a halt. He told us in good fluent English that there would be fifteen minutes rest.

'Men, for you the war is over! You are prisoners-of-war now. Obey orders, and you will get good treatment from us.'

One bright young South African asked if we could have a bathe.

Much to our astonishment he said, `All right! Ten minutes!'

We stripped and ran into the sea. The bathe was delightful after the hot dusty march over the desert sands. It didn't seem ten minutes when the German officer blew his whistle. As we were getting dressed, he remarked,

'One would think this was a health resort, not P.O.W.'s on their way to a concentration camp.'

He then said too that they would be in Cairo in five days.

Some chaps dared say, `Oh No, Sir...You will be stopped.' I personally thought he was right.

We were very close to the big main tarmac road. The mighty armoured Panzer Division which was roaring past at the time seemed to emphasize what the German officer had said a few moments before. The huge 105mm guns, Marks 1V tanks, armoured cars and other vehicles, motor cycles and staff cars... we saw a part of the great German Afrika Corps forging ahead with the Swastika very much in evidence. The rumble continued all night. Little did we think that the hard month's work we spent defending that defence line at El Alamein would eventually turn and stop that seemingly invincible steel Armada.

Thirst was our greatest bugbear for the first 48 hours after the fall of Tobruk.

On Tuesday morning we were handed over to the Italians. What a contrast to the German organisation and efficiency. The Italians lack of organisation was appalling...noisy, excitable and unreliable. We were conveyed by huge diesel trucks, each with one trailer attached to a Derna. We were so crowded that most of us stood all the way. We were put into a walled-in graveyard which had been used as a lavatory. It was so crowded that the majority of us had to sit up and sleep. I was one of the fortunate ones to leave for Benghazi the following morning. Some poor chaps had to endure this 'hell-hole' for four days.

Benghazi

We stayed at Benghazi for three weeks under canvas. There small bivouac tents were provided for us and we pitched these. There were quite a lot of chaps that went down with constipation and dysentry. I had the latter, but managed to recover, enabling me to go along with my pals. We were all members of the 2nd Anti-tank Regiment of SA.

About a week before we left Benghazi we had the great thrill of seeing five Boston Bombers overhead. They did some high-level bombing on shipping. Judging by the amount of debris that was thrown sky-high, one bomb scored a direct hit. We gave a great cheer. We were promptly stopped, the Italians threatening to shoot us if we shouted with such enthusiasm again. Their ack-ack round the Harbour went into action, but the bombers never even broke formation. What a thrill it gave us seeing our own planes.

We were out on a ship and packed down the holds. We were unable to lie down, and sat and slept all hunched up for two nights and a day. In order to relieve ourselves, we were allowed to go on deck to the latrine one or two at a time. Imagine the queue at the bottom of the ladders.

Italy:

We landed at Brindisi only too thankful to be off that stinking ship. We were put into cattle trucks a few hours after landing and taken to Bari, where we were herded into a huge canal for two nights and days, with no shelter or even shade. That evening we had our first hot meal and sweet coffee since capture a month before. The next day we were taken in batches, and barbers gave us a severe haircut.... a real crop. Then we had hot showers, which was a real treat.

We then marched to Camp 75 (Transit Camp). We were put into groups of fifty, in order to make messing easier. We lived under canvas... small bivouac tents. We were allowed to talk to our officers from the fence. We were also allowed to write two letters home at Bari and stayed there for 3 weeks.

Lucca: Campo di Concentramento 60.

Approximately 1000 of us were sent to Lucca about 20 miles from Pisa in Northern Italy. From our trucks we caught a glimpse of the countryside and en route, passed through Rome in the early morning. We could not see much, but got a much better view [of] Florence. Camp 60 was situated on a slight incline just off a low-lying vlei.

The surrounding countryside was very picturesque.....Low-lying wooded hills in the foreground and the bleak Apennine Range away in the distance, not unlike the Drakensberg. This was a summer camp.

We were once more put under canvas, the usual Italian bivouac tents, on arrival here. We were searched thoroughly, and all knives forks and even razors were confiscated. However, we soon made others out of heap iron, steel mirrors, and even big nails. We once had a week's rain. It swamped out the lower portion of the camp. It was untenantable, so the group I was in and the two other groups were shifted to a higher and drier area.

Nobody who was in the Campo di Concentramento No. 60 could ever forget it. We nearly died of starvation. The first 10 weeks we had no Red Cross parcels, and when we did get a whole parcel per man it was really gift from heaven. During the first few months we sank very low indeed. I remember having four blackouts in one day. Others had as many as ten in one day. Nearly every man lost forty to fifty pounds in weight in three months. Apart from this mere existence, I developed boils and sores. I was only one of many. I must say that the Trojan work done by Cpl. Green of our S.A.M.C. was just wonderful. The lack of bandages and ointments caused CPL Green to have terrific arguments with the Italian doctor and his staff. Things however did improve slightly when an Imperial Medic was attached. The arrival of the Red Cross parcels and English cigarettes was a revelation. I have no hesitation in saying that these parcels saved fifty percent of us from death. The change was astonishing. Instead of absolute despair, the chaps' spirits soared. We became more human and tolerant towards each other, and the pangs of hunger were appeased. New life, new hopes, and a better spirit of camaraderie gradually returned. Of course, some chaps, but not many, did crack up rather badly. They allowed the barbed wire and general conditions to pray on their minds to such an extent that they didn't care what happened.

Forming of an Agricultural Society.: In order to occupy our minds and time (which we had most of!) some of us called a meeting of all farmers and agriculturalists. a working committee. Mr Dix, the famous Shorthorn cattle breeder and cattle judge was elected out president. Six others were duly elected to the committee, and I was one of them. We mapped out a programme, deciding on a course of lectures every afternoon. They covered a wide and very interesting range of topics. We had a couple of sheep farmers from Beaufort West and a government sheep expert who gave very interesting talks on sheep farming and wool grading, Government officials from the Vaal harts irrigation scheme; a poultry farmer from Wambaths, Transvaal; a compost expert from an experiment station in Uganda and vegetable growing from a small farmer on the Cape Flats.

I am a plant disease inspector from the Division of Botany and Plant Pathology Dept of SA. I gave three lectures on the Sugar Industry of Natal, commencing from the early days when the Old Natal government first introduced Indian labour, the disease campaign and the introduction of new varieties and the wonderful work done by the SA Sugar Experiment Station at Mt Edgecombe.

Two other fellows who worked in the biggest factories gave other talks on the manufacture of sugar. One of my colleagues, Colin Law, gave lectures on citrus farming, nursery work and citrus plantations. Our gatherings were always well attended.

Education:

Teachers and other stout lads volunteered to give lessons in Afrikaans, Zulu Italian and German, bookkeeping and accounting in the mornings. Most of us took advantage of all this, but paper was very scarce indeed.

Gravina Campo di Concentramente No 65.

November 1942 : rains became far too frequent and it commenced to get so cold that the whole countryside at sunrise was a white sheet of frost. So on the 13th of November we were dispatched by train to Gravina Camp 65 in Southern Italy, about 50 miles from Bari. The usual trucks. No deluxe for POW's.

We eventually arrived on a cold, rainy, sleety and windy afternoon, and had to stand in all this while the Italians were sorting us out. At last we were put into a building. Our party was approximately 2000. This was a fairly big camp. We brought the complement up to 8000. The Italians divided the camp into four sections or satteries each holding 2000 men. Each section was an entirely separate unit having its own kitchens, lavatories and washhouses. The internal administration of each section was under a British or South African R.S.M. who appointed his own camp police, cooks, barbers, wood choppers and other fatigues and bay sergeants. All secured double rations thus employed.

All sergeant majors lived in a separate bungalow. Their food was cooked separately and was usually better than ours. They received double rations and some of them employed batmen. Shortage of fuel for cooking Red Cross parcel food was a real bugbear. Consequently in order to get firewood, bartering with the Italians sentries became a ramp. Occasionally, one poor unfortunate would be caught. He was put into detention by the R.S.M. In the dead of night one would wake up to see a huge leg or plank being carried into the bungalow, and they would immediately set about breaking it in to small pieces and hiding it underneath their bedding.

Brewing tea was a great event. All over the camp one would hear this remark "The brew must go on". On two occasions chaps were caught purloining shutters and window frames from the lavatories for fuel. The whole section was fined by the Italians some 45,000 lire. The "Brew" still went on! All sorts of blowers were made, charcoal being obtained from the kitchens by fair or foul means. My party had one that could boil a billy of water in 5 minutes! Stoves and tin mugs of all kinds were made from Red Cross parcel tins.

Xmas Day, 1942

Thanks to the Red Cross the majority of us shared a special Christmas parcel, one between two men. Xmas pudding and cake, lovely chocolate sweets.... Even the sprig of holly was not omitted. No one can realise what a wonderful God-sent organisation the Red Cross is more than the Prisoners of War. It turned mere existence into life and hope.

Amusements

After much battling by our R.S.M. an empty bay in one of the Bungalows was turned into a Concert Hall. Seats were made out of concrete a fairly good stage, somewhat oriental in effect. The curtain was made out of sheets. The lighting effect was good, even to the footlights. Sgt. Bosman from Cape Town wrote and produced most of the plays. Instruments (piano accordions, violins, drums etc.) were bought from the Italians from a camp fund to which we all contributed. The artists were surprisingly good, and some were dressed up as women. They were so well got up and acted their parts like professionals, that some chaps thought that women has been smuggled in. We spent some cheerful evenings in the "Happy Dome" which it was named.

Sport

Owing to limited space, basketball was the only game allowed. We saw some really fast and exciting matches by Imperials, who were outstanding.

About one thousand of us were unfortunate. We didn't get bunks for over three months. We had to sleep on pailliasses filled with a foot of straw, on the concrete floor. The straw was changed once in six weeks if one was lucky. By the end of April I doubt if one P.O.W. was free from lice. The disinfectors could not cope with this fearful menace. Delousing became the order of every morning.

Camp 65 was situated on a bleak ugly ridge. Wheatland could be seen in the distance... just the opposite to the lovely scenery one saw in Camp 60.

Working Camp120/X During April 1943 volunteers for farm labour were called for by the Italian Camp Commandant. We got in touch with our R.S.M about it. He assured us that it was quite in order and sanctioned by the International Geneva Convention. Sergeants P.O.W's were barred from volunteering.

On the 28th April one hundred and twenty of us left for a working camp. Only three members of my battery volunteered to go out into the blue with me. I was very sorry indeed to bid farewell to the rest of my pals whom I had lived and fought with for over twelve months in the Lybian desert. To mention a few of my closest pals: Sgt Eric Avenstrup, Bdr. Billy Wade, the SA cricketer, and Bdr John Thompson. It was tough to leave these good companions. However, rather than to continue living in that huge and dismal camp with its lice and eternal barbed wire and bleak outlook, I sought pastures new. It proved a wise move, as following chapters will reveal.

The train trip on this occasion was the best we have so far experienced. We were put into 3rd class coaches and were not overcrowded, as was previously the case on trips on trucks. About fifteen miles from our destination, 60 of the party was taken off and sent to a farm nearby, while the rest of us continued to chug along to Chióggia.

Two Italian officers and a Sgt Major with a small detachment of guards marched us through this little Italian Village for about 2.5 miles to St Anna Estate. The owner was a Swiss, and met us with his field manager. He spoke very good English. He asked for our leader. Tommy Carr was elected there and then, as we had not given much though to that. He proved to be popular and a very sound chap.

We were asked if we were lousy. It was only too true. We were stripped, and we put on our overcoats to hide our spindly legs and anything but robust bodies. All the rest of our kit was put into a huge stream and disinfected. In the meantime our hair was cut once more - not Eton, but the whole crop! After our kit had been steaming for several hours, it was hung out to dry. In the afternoon our overcoats were done. It was a really thorough job. That was the end of our little "bus pals"!

We were then conducted to our new domicile. Upstairs was a dormitory with 30 double bunks and a lavatory, showers and washing place. Down a flight of stairs our dining room and kitchen were located. New tables and bunks made life very much more pleasant. We had our own cook and orderly.

The farming operations;

We were divided into four working gangs. Each one of us was given a number to be worn on our headgear so as to be easily identified as P.O.W's. Some red cloth was cut into triangles which we had to sew on to our pants, and one each on our jackets and shirts.

Numbers 1, 2 and 3 gangs worked on St Anna Estate. I was put in charge of No. 4 gang. We worked on a Count's Estate farther away. We were fetched every morning by a motor vehicle with a small trailer attached. The first 6 weeks we worked with wheelbarrows and shovels reclaiming and levelling the fields. Each gang had an Italian foreman who showed us what to do. The first fortnight was very tough as we were still very weak, and it was backbreaking work. I must say our old foreman was very considerate. No one could call him a taskmaster. However, gradually we grew stronger and fitter. After a month or so, we had not only gained weight, but were cheerful, and could do ten hours work with ease. We worked on cleaning drains, canals and cutting wheat with sickles and worked behind wheat mowers. We also reaped fields of silk plant by hand, loaded wheat barges, and carried wheat up two flights of stairs into wheat granaries. We were often given extra wine and meals by civilian tenant farmers, especially during harvest season. Italian peasants were extremely decent to us all.

We were fortunate in getting one Red Cross parcel per week per man. Actually we fared very well compared with the chaps we left behind in the huge concentration camps.

I spent five happy months, the most pleasant period of our captivity. We had two concerts. They were surprisingly good. They helped to make things more like home. Occasionally we had some music. An Italian who in Civvy Street was a member of an orchestra in Rome, played the accordion very well. Italian opera and all the old classical favourites were played. After a while we even got to play some of our Afrikaans favourites, i.e. Sarie Marais, Suikerbossie and so on.

News:

Italian newspapers were bartered and bought from friendly guards and civilians. They were smuggled into the camp. L./Bdr. Eddie Wraith, a great pal of mine and one of the members of my old battery 2nd Anti-Tank, transcribed the chief items of war news into English. We used to collect around his bunk after we were locked up for the night. In whispers he used to tell us how our cause was faring. We managed to follow the course of events.

El Alamein news : an Australian who was captured there gave us the news in detail while we were still at Camp 65. Here in this camp Eddie Wraith could give us the news of Tunisia, and after that of the capture of Sicily in 28 days. By September we heard the news of the Battles of Naples and Serlane.

P.O.W. pay : In the concentration camps we were paid 1 lire a day. At 72 lire per GBP1, this meant 3.5 pence. However, I don't think we ever got the full value in goods. One penny would be nearer the mark. During our stay in the working camp, we were paid 5 Lire per day. We had a canteen in our bungalow. Fruit, fish and vegetables, polish, razor blades, toothpaste, etc. and wine could be purchased.

CAPITULATION OF ITALY

On the 8th September at about 8p.m. the Station Sergeant Major in charge of our camp told us that Italy had capitulated! We were somewhat surprised. There were loud cheers! We had a real party. Wine was produced. Guards and P.O.W.'s had a sing-song. The Italians said they were no longer our enemies, but our comrades!

On the 9th we played cricket. All farming operations for us ceased. On the morning of the 10th at six o'clock, we were put on to a train with an armed guard, the Sergeant-Major in charge. We were taken to Padua, our administrative headquarters. We arrived there at about 8 o'clock. We were taken into Concentration Camp 120 in the city, and locked up.

MAKE A BREAK FOR IT!

At 10.30, Italian officers told us that the Germans were about to enter the town. They were opening up the camp! We were told to make our escape as best we could as they were unable to protect us any longer.

The Italians fled into the town and got into civilian clothes. We formed ourselves into small parties, grabbed some of our kit, but left most of it behind.

Our particular party numbered seven. On the west of the town some twelve miles away was a range of mountains. We made for them, and all seven of us reached them safely. However several chaps were caught by German Patrol cars within an hour of making the break.

The Germans entered the town at eleven.

I collapsed. My half-section, Gardiner, remained behind with me. The other five continued. I have never seen them since.

Gardiner and I spent the night in the huge monastery of Praglia. A monk, Father Isidore Tell who spoke English, was kindness itself. I had a couple of glasses of milk, then was put to bed. I slept like a stone. I felt quite O.K. the next morning. The monks gave me a good breakfast. Father Isidore Tell gave us a Shell Company road map of Italy, and we left. We heard a wild rumour that Venice was in our hands, so we made in that direction.

After walking about fifteen miles, keeping away from roads, we contacted a civilian Italian who informed us that our news was false : the Germans were in possession of Venice and all surrounding country as far as Rome, and even beyond. When night fell, we returned to the mountains.

The following Monday, we met two New Zealanders in the bush. They had been fortunate to change their battledress for civilian kit.

We met a couple of friendly Italians who invited us for lunch. It was very acceptable. About four in the afternoon we were still in the house when there was an alarm that Germans on motor cycles and side cars were patrolling the roads. We were taken up to an attic. From a window we could see the Germans driving up and down the roads.

We had supper too with this Italian family, then went into the mountains and slept.

The next morning we contacted two women who took us to their house. There we met their father, who was kind enough to exchange our battle dress for civilian clothes. This family said we could stay in the mountain and come down at night time for a meal. The old chap insisted on us sleeping in his hay loft.

We risked it for two nights, then we heard that six P.O.W.s had been caught by the Germans while asleep in a loft in the same locality. Our good Samaritan then suggested we sleep in a small shed in his vineyard. We accepted this offer because rain threatened.

The following day we met a South African and an Imperial. The former had been captured at Tobruk at Algiers eight months before. We invited them to join us. They shared our 'Villa Engelese', as our Italian friends called it.

PAMPHLETS PICKED UP IN THE WOODS:

One morning, Gardiner and I were sitting in our hideout in the mountain and saw a German plane flying just above the treetops, very slowly. A few hours later, we picked up several pamphlets written in Italian. We could make out something to the effect that if the Italians persisted in harbouring and feeding P.O.W's, the Germans would deal very severely with them. On the other hand, if these prisoners were brought to German headquarters, 1800 lire would be paid for each one handed over. Also something about Bagolia turning traitor....Our Italian was not good enough to understand all that was written.

Anyway, the old peasant brought one of these pamphlets to us:

'It's all German propaganda....have you found any?'

We said: 'Yes, we can only understand bits here and there.'

'Well,' said he, 'don't be afraid. I will not give you away to the Germans. They are wicked. Besides, if I did give you away, I would not get rewarded. They would still come and arrest me and burn my house down. Friends, you can stay here as long as you like. We will do all we can for you.'

The four of us continued there for about a week, sleeping in the `Villa Engelese', and returning to the hide-out at dawn.

Three families made arrangements to feed us. Girls used to bring us our breakfast : bread, milk and grapes. Lunch : macaroni or boiled chicken, meat, bread and wine...Dinner we had at the house. One of the sons always kept a look out all the time we were in the house in case of Germans.

Early one morning we were woken up by one of the sons saying,

'Tedeski!' ('Germans' in Italian) are at the house....'Get moving!'

We seized our kit. The son grabbed some kit too, and made for the bush where we stayed hidden in the undergrowth. About an hour later, a German armed with a Tommy gun and revolver passed within ten feet of me. A near thing! However we were given a quiet 'All clear!' at about eleven.

Lunch arrived as usual. We were told that nine armed Germans had visited the house, searched every room, lofts, outhouses and all. We knew of twenty-four chaps living in the vicinity. None were captured on that day. In our case it was only through timely warning.

We felt that we were endangering their lives and all that the family possessed, so we suggested going further afield. They persuaded us to stay, saying that the Germans had made a house to house search. It was not likely that they would do so again, more especially as they had captured no one. We used to spend a pleasant hour with the family every night, occasionally being invited to dinner elsewhere nearby. This part of Italy is thickly populated, and all available ground is under cultivation.

A PROPOSITION IS PUT TO US

One day, about a week later, a niece and girl-friend of our host arrived on a visit. The old boy told them all about us. His niece insisted on seeing us.

The uncle and the two girls arrived at our hideout. The niece asked us if we would like to make a break for it and try to reach our lines. We said that was our earnest desire.

'Well,' she said,'Tomorrow I'll bring a man to see you.'

We wanted to know all about him, which was natural, as he might be a German or a Fascist agent. She said he was not a Fascist, and could be trusted. We agreed to see him.

They duly arrived on bicycles. He was a big, well-dressed Italian who informed us that he was a wholesale chemist, and Head of a secret underground organization. He produced maps, showing us the route by which he intended taking us. We were to travel East for a certain distance by train, the north. The plan was to contact Partisans in the North-East of Italy. He said that he had already sent ten English prisoners on their way. They had reached a unit of the army of liberation. He saw that we were rather worried, so he said that he was not a German spy. He hated them. He had been a soldier in the last war and fought against the Germans at Caparretto. He invited one of us to go back to the town twelve miles away and talk to other members of his organisation. So Private Eric Prew, D.M.R.S.A. went. He said he would return the next day, and also bring us a better civilian clothes.

Prew returned the same evening. In his opinion everything was genuine and above board. The next day he and another fellow, who was one of his 'men', arrived. We changed into the kit he brought. The only thing he would allow us to take with us was our shaving kit. Papers, all military kit, even our boots, we gave to our Italian host. I made up a small parcel of personal snaps, a little Bible and paybook, which the good Samaritan promised to post to me after the war was over.

Saying good-bye to our kind friends was really sad. The women wept as they wished us good luck. The old Italian gave us 100 lire for our military kit.

He said, 'You will need this money for your long, long trip.'

WHICH ROUTE TO TAKE?

We asked the head of the organisation about the southern route down the centre of Italy. He said it was far too dangerous. Germans had now got full control as far south as Rome. All roads were patrolled, rivers guarded, and parachute troops controlled all strategic roads and passes in the mountains.

THE COMMENCEMENT OF OUR LONG, LONG TRAIL

The head of the organisation gave us 250 lire (approximately Ł4 in English currency). On the 30th September we left.

We walked about a mile, then caught a tram to the town about 11 miles away. We purchased our own fares. We had not gone more than two stages when a couple of Germans boarded the tram and sat two seats away from us! All the way on this tram, we saw Germans. However we reached the centre of the town safely. The streets were crowded with Germans, some arm in arm with Italian girls. Saloons, pavements and restaurants were all crowded out with German troops.

Our new friends finally led us to a house. There we met three more South Africans. We were given a hot meal and wine. The next morning, the seven of us were taken to the main railway station by two private cars, and on arriving at the station, we were given two tickets surreptitiously by the leader. We followed him into a train and sat down. He whispered to us that he was not going any further with us. We had to be very careful not to talk English to each other, and were to behave like any ordinary Italians.

'You see that chap sitting over there? He is one of my men. He is your guide from now on. Don't address him. When he leaves the train, follow him. Good-bye, and Good Luck.'

We travelled about forty-five miles maybe. Then our new courier got up as the train stopped at a small station, and alighted. We followed suit. He did not wait for us, but just continued down a narrow road until he reached a quiet lane. He then beckoned to us and gave us another railway ticket, and some Italian rations. He then told us to follow in two's and three's about two hundred yards apart. He was met by another Italian. They were two Italian lieutenants dressed as civilians.

We walked fifteen miles down country lanes and farm roads, crossing two main roads, and now and then passing German soldiers. Once we passed a cavalry regiment. The Germans were watering their horses. We passed within ten yards of them. At dusk we arrived at a big railway station. A big mail train steamed in. We individually got aboard at about seven, and travelled on until 10.30p.m. Our guide spoke to us just before the train stopped and said:

'You see that chap with the black jersey wearing glasses? He is your courier from now on.

I am not going any further with you. Goodbye and Good luck.'

The train stopped and we got out and walked some distance. We found that five more South Africans had joined us. Luigi, our guide, called us together. He told us that he had taken ten P.O.W.'s along this same route a fortnight before.

He had a whistle. One blast indicated 'Halt.' He would then go ahead to see if everything was clear. Two blasts meant 'Advance quietly and no talking.' Three blasts meant 'Danger, enemy very near...Disperse and seek shelter.' A blast after this would indicate his location.

Well, we went on our way in pitch darkness until about 3a.m. We arrived at a small village. I think Luigi intended us to doss down for a couple of hours, for he knocked at a door. After knocking several times, he was challenged, so he told us, in German, and as the door opened, he flashed his torch on. He saw a German carrying a rifle. Another followed, close behind, also armed. Anyway, we heard him shout, 'Tedeski!' and he blew his whistle three times. He beat it down the road, we in hot pursuit. A chap dropped a suitcase in the road containing our rations. I picked it up and ran. We came up to Luigi, then his under a bush for some time. Five chaps were missing. Eric Prew and the Imperial were two of them. We never contacted nor heard of them again.

As soon as it was light, we went to a house where we had breakfast. While we were enjoying our meal, a German walked into the yard. The farmer walked out. He and the German talked for quite ten minutes. Then we went on to the village we had vacated in such a hurry. We walked until midday. We were going to a roadside restaurant to get a meal, however Luigi discovered that a German party had turned the place into their Headquarters. We had a snack in the forest from the suitcases. That night we slept in a loft, and had a hot meal with a friendly Italian family.

Early the next morning, we were on our way. At about two o'clock, after climbing a high mountain, we arrived at a small fort on a little plateau, not before being challenged by a sentry. Luigi did his stuff. We were told to advance. Then we were brought before the Captain of the band, and we all shook hands. We had reached the first Partisan outpost. We were all accepted as comrades. Cigarettes and food were given to me. This party consisted of twenty-one men and one woman. They were well equipped with small arms -

Tommy guns, about six machine guns, and hand grenades of all kinds.

That same evening, with the exception of the woman, the guard and me, who were left to guard the fort, they all went down to the village and raided a Fascist magazine and Quarter stores. They returned in the small hours with a motor bike and trailer, boots, rifles, cigarettes, chocolates, etc. we remained there for three days. We said Goodbye to Luigi, who returned. A new guide was provided and we went for ...'

(At this point Roy's original hand-written documentation stops...so Clive and I have added what we remember from when we had listened to Roy telling his story on a number of occasions...)

...miles through Italy, with guides passing the men safely from one to the next, guiding them from one form of shelter to another.

They were presented with two options for escape routes: via Switzerland, or the Balkans?

Roy did not want to go to Switzerland, but preferred to make his way through the Balkans.

The small band crossed the border into Yugoslavia and met up with Marshall Tito's Alpine guerillas, who were continually harassing the German patrols. Although they joined them, they were not allowed to carry arms, but were used as pack mules to carry arms and supplies on foot for the troops. Skiers would go off ahead, and they would doggedly follow their tracks in the snow. This riff-raff army was comprised of 'troops' of all ages, down to 16 year old females, all trying to protect Yugoslavia from the Hun.

From 8.9.1943 until early December (from the time when their party left Venice and headed northwards into the mountains) they turned and pressed on southwards through the snow, most of them getting severe frostbite. Once two girls on skis who belonged to the underground left them hiding in a forest while they sped across open fields leaving their tracks to show the men the way.

They arrived in Durrësi (near to Tirana in present-day Albania). From there they managed to get a ship to cross the Adriatic to join the Allied lines.

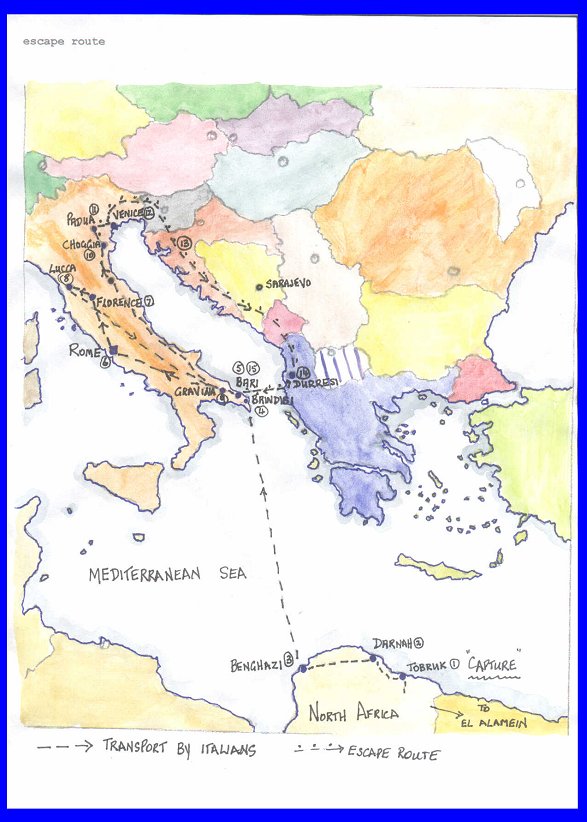

Escape Route

At this stage, Roy weighed 95 pounds. He had joined up at about 180 pounds. This necessitated almost a year's recuperation at Robert's Heights Military Base in Pretoria, prior to recommencing a normal civilian life, and going home.

a sample of Roy's handwritten account

The family had still to wait many months before being re-united, but at least the horrible doubt was gone.

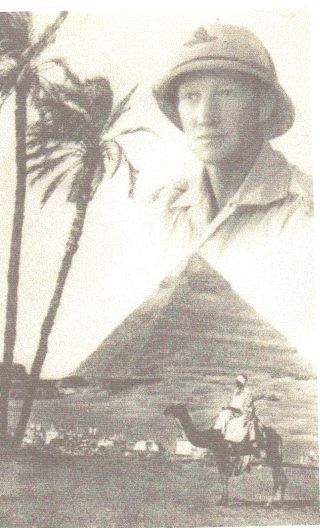

Father and son before the war (1939)

The years between : Clive, the wolf cub

'White Fang', the 'Sixer'

A-Ke-La 'We will do our best!'

Roy Halse in Egypt, 1941