Newsletter/Nuusbrief 192

September 2020

Our Zoom format of meetings continues at pace and we are attracting a wider than scope of members beyond our own local society and have found that others unrelated to us have also joined us as guests for the evening. There is obviously a concern that there are those who do not have access to Zoom are being left out in the cold and to reach an amicable balance, discussions are and have been held to make us more inclusive.

It would appear as if a solution could be to continue with the Zoom format and on a quarterly basis also have a local day outing to which all will be invited. These visits could include trips to Grahamstown, the Bathurst area, to nearby Nanaga and also our City tour which we hold in November.

In order to maintain the interest, we have agreed to hold a second meeting every month and this will take place on the last Monday of the month. At this meeting a suggested programme will include a book review and there after a discussion on the book. Andre Crozier was the first up and at our meeting on 31 August reviewed the book called, “Louis Botha – a man apart” by Richard Steyn. A remarkable man of little formal education who became a Boer General and later the first Prime Minister of the Union. One who is said to have been overlooked in his achievements in the context of South African politics.

Andre would like to hear from you should you have a book that you would like to review and add to our interest. Kindly contact him. There is always the opportunity of covering an event and/or site in our five minute Member’s slot and we encourage members from where ever to participate. The more the merrier!

At this second meeting, Mac Alexander gave a talk on the late Sergeant Major Jock Hutton, who recently died at the age of 94 years and who, only a year ago, parachuted into France as he had done on 6 June 1944, to celebrate the 75th Anniversary of the Landings. A remarkable soldier.

Members may be aware that a section of the outer wall at Fort Selwyn, which is situated adjacent the Settler Monument in Grahamstown, has collapsed, but we are pleased to hear that the damage is covered by insurance and repairs will be suitably undertaken.

MAIN LECTURE - KNIT YOUR BIT: PATRIOTIC KNITTING

An Illustrated Zoom Talk by Barbara Ann Kinghorn on 11 August 2020

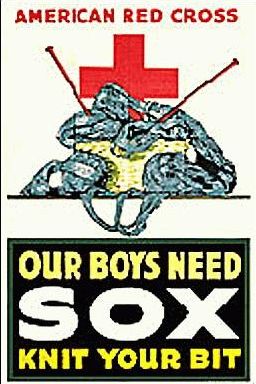

RED CROSS POSTER, c1917.

American Red Cross poster, by L.N. Britton requesting people to knit

socks to send to troops in Europe during World War I, c1917.

This is the poster that led me to discover who “our boys” were, why they needed “sox” and what “knitting your bit” means. My research was conducted entirely on the Internet, where, predictably, the environment is more than awash with information and half-truths: a tsunami of images and text awaits you when your key words are “knit your bit patriotic knitting”.

In this case, the American Red Cross is visibly behind the poster’s message, which urges American viewers to knit socks for American troops away in Europe during World War 1. The troops specifically needed lots of dry socks to prevent their feet from getting “trench foot” from prolonged exposure to damp unsanitary conditions in the trenches. The Red Cross provided yarn, knitting needles, patterns, sock knitting machines, assistance for novice knitters and distribution of the knitted garments to troops on the front. Indeed, knitters could even specify to whom their handiwork should go. For example, before the USA entered the war, American knitters could sew labels into the garments: some charming examples were for “a French soldier”, “a fighting Belgian”, “an Italian Marine” or “an Englishman of Gentle Birth in the Trenches”. Later, to simplify the logistics of distribution, knitters could still add a label indicating which specific US warship crew they wanted to receive their work.

But more than all this, the knitting campaign was designed to enable people on the home front to feel they were doing their patriotic duty and making a valid and valuable contribution to the war effort. Knitting patterns proclaimed “If you can KNIT, you can do your bit!”

The campaign was so successful that, at the end of World War 1, the total number of garments knitted was 23 million separate items, which included not only socks, but sweaters, gloves, hats, vests, balaclavas and “amputation covers” too.

Wartime knitting, it can be seen, was so much more than a hobby or a useful way to pass the time. It was without a doubt very effective propaganda. Knitting was also fashion and therapy for the knitters and a reminder of home for the recipients of lovingly knitted military garments. Ultimately, “knitting for victory” was about everyone being able to fight together for survival. In times of trial, patriotism can unite us and everyone can put their differences aside to help their countrymen in need.

This aspect of Military History is what I’m interested in – the different ways that “noncombatants” and people on the home front feel themselves called to do their patriotic duty in wartime. I have already made presentations about Vera Gedroits, a Russian princess who became a pioneering military surgeon; Anna Coleman Ladd, a sculptor from Boston who worked in Paris from 1918 -1919 under the aegis of the American Red Cross to alleviate the suffering of French soldiers whose faces were awfully disfigured in combat, by minutely creating portrait masks which hid their poor broken faces. And “The Lady in White”, Perla Seidle Gibson, a South African opera singer, who sang rousing patriotic songs to each troop ship or hospital ship that entered or departed from Durban harbour during WW2.

The wholehearted participation of men and women, old and young is clearly seen in an article about a “knitting bee” in Central Park, New York in 1918, organised by the Comforts Committee of the Navy League. At the end of the three-day event, they had raised $4,000 (roughly $70,000 today), created 50 sweaters, almost as many mufflers, 224 pairs of socks and 40 “wool helmets”. The same article also documents prisoners at Sing-Sing Prison, New York, knitting to the accompaniment of a mandolin club in 1915.

Kitchener Stitch suggests that even Lord Kitchener knitted, but that is not so. The invisible grafting at the toe of a knitted sock was probably invented in 1880, but in a 1918 sock pattern, it was patriotically named in Kitchener’s honour by Vogue magazine.

Unfortunately, not all knitters were experts though, as can be gathered from this soldier’s doggerel about his socks:

Glad to hear

You’re doing your bit –

But who the .......

Said you could knit?! M/ul>

To correct this state of affairs in WW2, the Red Cross hired a Mrs Brown to check the quality of socks knitted by others and to fix them. “Mrs Fix-It” apparently simply ripped mistakes undone and started again. She claimed she could repair 200 pairs of socks a week!

When WW2 broke out, practically everyone in Britain enthusiastically took up their patriotic knitting again – even prisoners, patients in mental hospitals, wounded servicemen in hospitals... and children. All this is described in a blog article called “Knitting for Victory” by the author Elinor Florence, who lives in British Columbia, Canada.

She asserts that “Literally millions of women, children and men in Allied countries used their knitting needles as weapons of war. If you weren’t a knitter, you might as well have been a Nazi!” and quotes the following jingle from a wartime pattern book:

War workers in Britain also learned to knit while they waited – emergency workers, bus drivers and London cabbies. By the end of WW2, 10 million garments for able-bodied servicemen and women and 9 million “Hospital Comforts” had been knitted. Even the Queen and Princesses Elizabeth and Margaret took up knitting for their troops.

And in fact, there’s a good case to be made that the Princesses’ paternal great-greatgrandmother, Queen Victoria, made patriotic knitting possible in the first place. Before the early 19th century, knitting was simply a folk craft and cottage industry, something the poor did from necessity to earn a living.

But it is said that Queen Victoria invited Irish knitters to the palace to teach her both knitting and crocheting, which she loved, and also spinning. So, thanks to the Queen’s example, knitting became something all socioeconomic classes could enjoy doing in the 19th century.

Furthermore, it could be said that the Queen herself invented “patriotic knitting” by setting the example for making “comforts” for soldiers in the field. At the age of 81, (in the last year of her life) with failing eyesight caused by cataracts, the Queen personally crocheted eight scarves (“The Queen’s Scarves”) to be awarded to eight gallant soldiers serving in the Second Anglo-Boer War. The scarves were about nine inches wide and five feet long, with four-inch long fringes at each end. The yarn used was Berlin worsted wool in shades of brown/khaki and each scarf has the royal cipher on it which the Queen embroidered: VRI – Victoria Regina et Imperatrix (Latin for Victoria, Queen and Empress).

But, the personification of the faithful wife knitting for twenty years while her husband was away at war must surely be Penelope, waiting for Odysseus? Not so: in the Homeric epic, Penelope was a weaver, not a knitter.

The confusion arises from 1831 when Gravener Henson, a workers' leader from Nottingham, England, and a historian of the framework knitters, wrote that Penelope was indeed one of them: a framework knitter. As knitting frames became obsolete, people erroneously pictured Penelope with her portable knitting, two needles and yarn – practising a craft that was probably only invented in Egypt between 500 and 1200 AD.

The oldest known examples of single-needle “knitted” cloth, made by nalbinding, (not the same as knitting) date from about the 4th century AD. Knitting as we know it, using two needles, with the yarn to be knitted fed by the right hand, (also known as English knitting) was probably first made by Muslims employed by the Spanish Christian Royal Families in the 13th century AD. The German, or Continental, knitting technique uses the left hand to feed the yarn to be knitted. Crocheting is a relatively new technique and dates from the early 19th century in Europe.

In A Tale of Two Cities, one of Charles Dickens’s most memorable characters is a knitting woman, or tricoteuse, Madame Defarge, who notoriously continues to knit at the foot of the guillotine during public executions in the French Revolution. She supposedly also uses a code in her knitting for keeping the names of aristocrats she plans to send to the beheading machine.

This practice of concealing messages or information within other non-secret text or data is called steganography and it is said that steganography was often used in WW2, where secret messages were decoded from various knitted pieces. Steganography is popular even today, not in knitting, but in binary code, among cyber criminals.

Knitting as an espionage tool is not well documented on the Internet, with very little hard evidence to be found, but there are lots of rumours about how knitting women have spied on the enemy, unnoticed, and knitted secret messages into their work. One old lady is often quoted though: we could perhaps call Molly “Old Ma” Rinker a very patriotic knitter for using her knitting to send critical information about British troop movements to George Washington during the American War of Independence.

Hand-knitting goes in and out of fashion and in between, it usually resumes its stereotypical role as an old-lady-by-the-fireside pastime, but it seems knitting in the 21st century is taking a new path. For instance, some knitters are “guerrilla knitters” pushing conventional boundaries and becoming activists who challenge the status quo through their knitting or crochet work. Their Yarn bombing -a type of street art or graffiti -uses colourful public displays of knitted or crocheted yarn or fibre, rather than paint or chalk, in a challenging and sometimes aggressive way.

Also known as wool bombing, yarn storming, kniffiti or graffiti knitting, it was started by Magda Sayeg in Houston in 2005 when she covered the door handle of her boutique with a knitted cosy and liked it so much, she then proceeded to cover a stop sign’s pole with crochet and so inspired an enthusiastic following doing similar things all over the world.

Other contemporary knitters like some on www.ravelry.com, undertake knitting projects such as the unsettling Doomsday Knits project -for the apocalypse and after, edited by Alex Tinsley. But knitting for someone else’s warmth and comfort is not fashionable anymore and doing your patriotic duty it seems, if anyone even thinks of it at all, is a quaintly old-fashioned concept.

With the advent of the present COVID-19 pandemic, and with the wisdom of past experience, I expected that knitting would be harnessed yet again by the authorities managing our present time of global crisis, as a morale-boosting unifying activity, but instead our natural human instincts are thwarted at every turn. Because our fellow human beings spread the invisible enemy everywhere, not just at some far-away battlefront, we are admonished to stay at home as much as possible, to keep a safe distance from others, to hide our faces with masks and to wash our hands in a neurotic, OCD kind of way for our own safety and that of others. Group activities are a bad idea, so what can we do to express our solidarity with each other?

This research has taught me that knitting our bit, apart but together in the endeavour, is probably just what we need. Winter is always coming and there will always be people who need warm clothes, so I have started knitting again... a scarf for a king (complete with my monogram embroidered on it =-)) and now squares for a blanket and then I’ll knit a nice warm hat and then some mittens...and maybe one day I’ll even produce some sox.

Try it: research has proven that knitting your bit is actually good for you!

SOURCES

https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/knitting-spies-wwiwwii?utm_source=Atlas+Obscura+Daily+Newsletter&utm_campaign=fde1349aedEMAIL_ CAMPAIGN_2019_08_07&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_f36db9c480-fde1349aed67515365&ct=t(EMAIL_CAMPAIGN_08_07_2019)&mc_cid=fde1349aed&mc_eid=8650bce697

https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/when-knitting-was-a-patriotic-duty-wwi-homefront-woolbrigades

https://www.elinorflorence.com/blog/wartime-knitting/

https://www.ravelry.com/

https://www.irishtimes.com/life-and-style/people/purl-power-why-i-quit-my-job-to-knit-my-wayaround- ireland-and-britain-1.3999904

“Defense Knitting: Women’s Volunteerism During the First and Second World Wars” -doctoral dissertation by knitting historian Rebecca Keyel

https://centerforknitandcrochet.org/knit-your-bit-the-american-red-cross-knitting-program/

A History of Hand-Knitting by Richard Rutt

No Idle Hands: The Social History of American Knitting by Anne L. Macdonald

Knitskrieg: A Call to Yarns!: A History of Military Knitting from the 1800s to the Present Day by Joyce Meader.

To Contact Barbara Ann Kinghorn: +27 (0)41 373 4469 or coraltreeB@gmail.com

Our monthly meeting will be held on Monday 14 September; see below the joining details. The Main Talk will be presented by Pat Irwin on The Royal African Corps, who served in the Cape in the period 1817 – 1823. A penal regiment which, by all accounts, had their own particular history!

SAMHSEC is inviting you to a scheduled Zoom meeting on 14 September 2020.

Session 1:

Topic: SAMHSEC's Zoom Meeting Session 1

Time: Sep 14, 2020 19:30 Pretoria

Session 2

Topic: SAMHSEC's Zoom Meeting 14 Sep 20 Session 2

Time: Sep 14, 2020 20:15 Pretoria

Our second meeting in September will take place on Monday 28th and joining details will be provided in due course along with the programme.

Ian Pringle - Scribe.

| Chairman: | Malcolm Kinghorn | culturev@lantic.net |

| Secretary: | ||

| Scribe (newsletter): | Ian Pringle. | pringlefamily@telkomsa.net |