Newsletter/Nuusbrief 172

January/Januarie 2019

The December meeting took place on the 10th December at the usual venue in Port Elizabeth.

The members’ slot was used by Malcolm Kinghorn who addressed the coincidence that the first and last ‘killed in action’ casualties of the Bush War were both from 1 Reconnaissance Regiment, namely Lt Fred Zeelie on 23rd June 1974 and Cpl Hermann Carstens on 4th April 1989.

The curtain raiser, an illustrated talk presented by Barbara Kinghorn, was titled Face-saving in 1918.

A hidden history revealed

World War 1 archives contain extensive medical records and artefacts relating to some 60 500 facially disfigured survivors of WW1, but for decades they were kept hidden. The horrific consequences of mechanized warfare wrought on human beings are well-documented in X-rays and surgical diagrams, photographs and stereographs, plaster casts and models, and only fairly recently have researchers begun to examine the visual evidence of this hidden history and to publish and exhibit their findings.

The extent of WW1 facial injuries was shocking. Many soldiers survived with monstrously damaged faces, so distorted that they barely looked human. After the war, they dreaded returning to their families and having their own children flee from them in fright – which indeed happened, and as a result many chose not to go home at all. To attempt to alleviate their misery, some remarkable surgeons and artists collaborated to 'save their faces' through what is now called anaplastology: the art, craft, and science of restoring absent or malformed anatomy, through artificial means.

For many young men of the British Empire it all started in August 1914 when they responded to appeals urging them to join up, lend a hand, to fight in France.

Victorian Romanticism about War quickly evaporated in the face of modern industrialised warfare where new military technology, particularly that of artillery and machine guns, caused utter devastation of the physical landscape and unspeakable injuries and facial disfigurement of many soldiers wounded in battle. Those left without faces lost their identities, self-esteem and self-confidence and lived with the bleak truth that their appearance was repulsive to everyone who saw them.

At the start of the war those wounded to the head were generally not considered able to survive and they would not be 'helped first'. But military medicine quickly improved so soldiers survived previously fatal head injuries, having sacrificed their faces in the process.

Robert Tait McKenzie, an inspector of convalescent hospitals during the war, described the facial patients at the 3rd London General Hospital as ‘the most distressing cases’ in military surgery: “The jagged fragment of a bursting shell will shear off a nose, an ear, or a part of a jaw, leaving the victim a permanent object of repulsion to others, and a grievous burden to himself. It is not to be wondered at that such men become victims of despondency, of melancholia, leading, in some cases, even to suicide.”

“Hideous is the only word for these smashed faces: the socket with some twisted, moist slit, with a lash or two adhering feebly, which is all that is traceable of the forfeited eye; the skewed mouth which sometimes — in spite of brilliant dentistry contrivances — results from the loss of a segment of jaw; and worse, far the worst, the incredibly brutalising effects which are the consequence of wounds in the nose, and which reach a climax of mournful grotesquerie when the nose is missing altogether”- from Ward Muir's The Happy Hospital, which was published in 1918. Muir was a corporal in the Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC)

In the course of the war, surgeons like Hippolyte Morestin, Harold Gillies and Léon Dufourmentel made enormous progress in oral and maxillofacial surgery and most notably in the new field of plastic surgery, as they conducted experiments to rebuild facial features with bone, cartilage and tissue transplants. Because of the experimental nature of this surgery some patients chose to remain as they were and others could just not be helped yet. Some of the latter were helped by the skill of remarkable ‘Face Saviours’ – surgeons and artists - and all kinds of new prosthetics which made them look more or less 'normal'.

Face Saviour #1: Henry Tonks FRCS (1862 - 1937) British surgeon and artist

Having initially trained as a surgeon, Tonks decided he was not any use as a doctor and instead became an artist who taught drawing and became a professor at the Slade School of Fine Art in London. In 1916 he obtained a temporary commission as Lieutenant at Aldershot Military Hospital, assisting Harold Gillies in facial reconstruction. One of Tonks’ roles was to draw preparatory line diagrams for delicate reconstructive operations. The 72 pastels he created show not only the pre-operative status of soldiers’ facial wounds, but also captured a sense of their humanity and suffering. They remained hidden until recent interest in the full graphic record of the war reasserted their value. Tonks' images of wounded servicemen are now iconic because they allow people to see what was previously kept hidden: the horrific consequences of mechanized warfare on the human face.

Face Saviour #2:Dr Harold Delf Gillies (1882 – 1960) New-Zealand-born pioneer of plastic surgery

Gillies was 32 and working as a surgeon in London when the war began, and shortly afterward he left to serve in field ambulances in Belgium and France. In Paris, he was able to observe a celebrated facial surgeon at work, the French-American dentist Auguste Charles Valadier, and as a result of this and field experience of the shocking physical toll of the new war, he became determined to specialize in facial reconstruction. When his surgical intervention was not able to mend mutilated faces, Gillies then collaborated with artists to create likenesses of what the men had looked like before their injuries, to restore, as much as possible, the man’s original face. Rifleman E. Moss, for instance, badly needed a prosthesis to hide the awful damage to his face which couldn’t be surgically corrected. Gillies later remarked, “Fitted with an external prosthesis, at least he was presentable enough to be a blind man.”

Face Saviour #3: Francis Derwent Wood, (1871 - 1926) English sculptor

Captain Wood founded the Masks for Facial Disfigurement Department, known as the “The Tin Noses Shop”, at the 3rd London General Hospital in London in 1917. Along with several members of the Chelsea Arts Club, Wood created portrait masks for severely injured soldiers until 1919. “My work begins”, he wrote in The Lancet, “where the work of the surgeon is completed. When the surgeon has done all he can to restore functions … I endeavour by means of the skill I happen to possess as a sculptor to make a man's face as near as possible to what it looked like before he was wounded”. His art helped soldiers to overcome the loss of identity associated with facial injury, and to humanise those whose bodies bore the proof of war's essential inhumanity. No records exist of how many face-masks were made but there could have been hundreds.

Face Saviour #4:Anna Coleman Ladd (née Watts) (1878 - 1939) American sculptor

When news of Captain Wood’s work reached America in 1917, Boston-based fellow sculptor, Anna Coleman Ladd felt an instant need to offer her skills to facial patients recovering in France. Under the sponsorship of the American Red Cross and in consultation with Wood, she opened a small Studio for Portrait Masks in Paris in November 1917, which continued to operate to the end of 1919.

Often described in articles as a ‘socialite’, Ladd was born in Bryn Mawr, Philadelphia, and educated in Europe where she studied sculpture in Paris and Rome. At the age of 26 she moved to Boston when she married Dr. Maynard Ladd, and there studied for three years at the Boston Museum School. Her sculptures were mostly decorative fountains—nymphs and abounding sprites dancing — as well as rather bland portrait busts. Ladd’s studio in the Latin Quarter of Paris had a homey interior which she designed specially to give comfort and dignity to her badly disfigured patients while she and her assistants went about making their cosmetic masks.

Anna Coleman Ladd, American sculptor,

applying finishing touches to a facially disfigured

French soldier's portrait-mask in 1918.

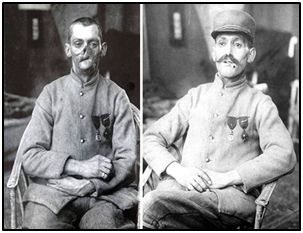

Before and after.

The scarred veterans’ transformation began with a suffocating plaster cast process used to capture each of their new imperfections. Using pre-war photographs of each soldier, and in consultation with their families, Ladd and her assistants re-created their missing features on the cast with clay or plasticine. A form was then taken from this and electroplated to form an extremely thin galvanized copper prosthetic piece. This became the metal portrait mask which was carefully painted with hard enamel to match the recipient's complexion. If needed, painted glass eyes were added and real hair for eyebrows and lashes. Painstaking details were also added to make the masks as realistic as possible – a moustache to twirl, and a special gap between the lips to hold a cigarette.

The completed mask was carefully fitted and hooked over the ears, or with ribbons if the person preferred. Each mask took about one month to produce and only cost about $18 due, in large part, to the fact that Ladd’s services were entirely donated. Reports vary as to the number of masks that she and her team created. Some say 60, others say over 100.

One of Ladd’s patients was a man who had refused for more than two years to return home because he did not want his mother to see him. He lived in seclusion, hiding his gargoyle-like appearance, until he met Ladd. Wearing the mask Ladd created for him, the young man was finally able to return to his family and face the world again.

Ladd’s fine art remains a mere footnote of late 19th century/early 20th century American neoclassicism, but the legacy of her face masks had an extra dimension - they restored the humanity of broken men. She proudly declared “I was able in every case to give the mutilated, disheartened man back his personality, and his hopes, and ambitions.”

The letters of gratitude she received from her ‘victims of war’ are glowing proof of her achievement. They tell of new jobs, marriages, and happy family reunions. “The letters of gratitude from the soldiers and their families hurt, they are so grateful,” she said. “Thanks to you, I will have a home” one soldier wrote to her. “The woman I love no longer finds me repulsive, as she had a right to do.”

Ladd's face-saving work also contributed significantly to the field of anaplastology. In 1932 Anna Coleman Ladd had the rare distinction of being awarded the Légion d’Honneur Croix de Chevalier by the French Government, since membership in the Légiond'Honneur is restricted to French nationals. Foreign nationals who have served France or the ideals it upholds may, however, receive a distinction of the Légion, which is nearly the same thing as membership in the Légion. Serbia also recognised Ladd’s face-saving work by awarding her the Serbian Order of St Sava.

The main lecture, titled An American connection - romance lost and won in southern Africa at the start and end of The First World War was delivered by McGill Alexander.

At this time, as we emerge from four years of focusing on the events of a century ago, when our planet was plunged into a cataclysmic conflict and the carnage of the First World War, I feel it may be appropriate to share two intensely personal tales that I have come across in my travels. They involve two of my favourite places in Southern Africa, each of which produced a sad but beautiful story that is closely coupled to that conflict. There is a poignancy in each account, reminiscent of Ernest Hemingway's A Farewell to Arms.

They are very different stories about Settlers to Africa. Both are about beautiful American women: one a socialite, the other a philanthropist, but both of them possessed of a great spirit of adventure. The first story concerns a wealthy German aristocrat, the second an ordinary South African of some sporting ability but very limited means. One tale is about a German officer; the other is about a South African private soldier. One came about because of the start of the war; the other because of the end. In the first story, a castle was built; in the second, a beach shack. One story played out on the western side of southern Africa; the other on the eastern seaboard. The scene for each is radically different, but both areas are indescribably beautiful. Both stories involved horses.

Captain Hans-Heinrich von Wolf and Jayta Humphries (Duwisib Castle)

Born in Dresden in 1873, the son of a Saxon major general, Hans-Heinrich von Wolf was commissioned in the Artillery. He later served as a riding instructor at the Military Equestrian Academy at Hanover. In 1904, when the war with the Herero and Nama tribes in the colony of German South West Africa (today’s Namibia) broke out, he volunteered for service with the colonial Schutztruppen. He saw action and was decorated by both his native Saxony and by Prussia. He was deeply impressed by the vastness of the deserts and mountains, the grandeur of the canyons and the bushveld and the solitude of Africa.

While on leave in Germany to recuperate from wounds, he moved in the social and diplomatic circles and met the beautiful stepdaughter of the US Consul-General in Dresden. The vivacious Jayta Humphries of New York was swept off her feet by the handsome, dashing young officer, returned from the wars in the colonies! The war had ended in the meantime and Hans-Heinrich decided to leave the Army and settle as a farmer in German South West Africa. He knew exactly who he wanted to share his life in the colony with! Jayta accepted his proposal and willingly embarked on this adventurous life in the wilderness. They married on 8th April 1907 and on 25th April they set sail for Africa from Hamburg.

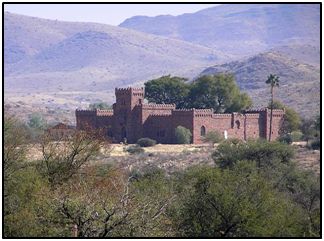

After landing at Swakopmund, they went to the capital of Windhoek and purchased several farms in the Maltahöhe area. There, in the remote hills known as Duwisib, on the edge of the Namib Desert, 70km from the little village of Maltahöhe, they began to construct their dream home. The recent war clearly influenced their choice of design! It was to be a fortress, built along the lines of a medieval castle of neo-Baroque appearance.

They commissioned a well-known architect of the colony, Wilhelm Sander, to design it. Measuring 35 x 31 metres and built in a U-shape, it had metre-thick walls constructed from locally quarried stone and was made to withstand a siege. It had a well in the courtyard and battlements all around, was equipped with heavily reinforced doors and narrow windows that could serve as firing ports. But Sander also incorporated all the comforts of a modern house of that era. The plumbing and sanitation fittings, along with steel, woodwork, cement and lighting all had to be shipped from Germany to Lüderitzbucht. From there it was transported in 20 ox wagons across 330km of harsh desert to where the castle was being built at Duwisib. Stonemasons were hired from Italy, Sweden and Ireland.

Duwisib Castle, Namibia.

Hans-Heinrich and Jayta lived in a tent on site, as did the construction team. The newly-weds actively assisted with the building operations, and the society girl from the East Coast of America proved to be the ideal match for the colonial soldier turned rancher. She took to the rough frontier life with ease and loved the harsh desert landscape. Her husband planted the palm trees in the courtyard that can be seen to this day. By mid-1909 the castle was complete! It had 22 rooms, including an impressive ‘Knight’s Hall’ as an entrance foyer, a singer’s gallery, a magnificent dining room, large kitchen, bathrooms, wine cellar and smoking room. The castle was equipped lavishly with period furniture and lovely paintings, while beautiful cavalry sabres and firearms adorned the walls. There was a grand opening festival organised to celebrate the completion of the project, and dignitaries from all over the colony were invited. It took them days of travel to get to the remote location, but the Von Wolf couple were the toast of the colony!

The Knight's Hall.

Hans-Heinrich stocked his vast, semi-desert estate with 95 Hereford cattle, 18 mules and donkeys, 600 merino sheep, 10 pigs and 60 chickens. But it was horses that really interested him. He had seen the potential for supplying the colonial police with mounts from local stock, rather than them having to import their horses from Europe. With his expert knowledge of horses, he set about building up some breeding stock and imported 72 horses of which 38 were mares of value. Nine were thoroughbreds. By 1911 his herd of horses had grown to 350 and he had established a flock of 8500 black karakul sheep. Obviously an astute businessman, he had appreciated the lucrative market for these fleeces. But he was also active in the community. In 1909 he had been elected to the local council for the Maltahöhe District and he also served on the Landesrat, an advisory assembly to the colonial government. Unusually for that colonial era, he also propagated the treatment of the indigenous local people by the health clinics in the rural areas.

However, Hans-Heinrich had a wilder side to him and developed a reputation for eccentricity. One legend has it that he would ride into the bar room in Maltahöhe on horseback and shoot all the bottles on the shelves behind the bar counter! Jayta, on the other hand, was a serene and gracious presence in the castle, reading, keeping herself busy with needlework and being the consummate hostess to the frequent visitors who spent time at their strange desert abode. The couple had no children.

Anxious to improve their breeding stock of horses, Hans-Heinrich and Jayta decided to go to Europe to select and purchase additional animals. They embarked on a ship in Swakopmund early in August 1914, bound for Hamburg. But by then the assassination in Sarajevo of the Archduke Ferdinand of Austria and his wife Sophie had already set the events in motion that led to war in Europe. While the colonial couple were at sea Britain declared war on Germany and the ship was forced to divert to Brazil.

Jayta Humphries had retained her American citizenship and found passage for them to Europe from Rio de Janeiro via the USA on a Dutch ship; Hans-Heinrich had to hide when the ship was stopped and detained by the British Royal Navy. On arrival in Europe he re-joined his old regiment in the German army. He was promoted to major and sent to Flanders, where he was wounded. Even before he had fully recovered he was sent back into action to command a battery of artillery and died from wounds sustained during the aftermath of the Battle of the Somme.

Following the death of her husband, Jayta moved from Dresden to Munich, where her stepfather was then the US Consul General. She later married the German Consul-General for Siam (now Thailand). She could never bring herself to go back to South West Africa and never saw the Castle of Duwisib again. With Hitler’s rise, she moved to Zurich in Switzerland and in 1946, after the Second World War, she returned to her homeland of the USA, living with her parents in Summit, New Jersey. She died in the early 1960s.

In her last years, when asked about the time she spent in the German colony of South West Africa, Jayta would smile and say, “Ah, that was an interesting experience, you know!” She and her beloved Hans-Heinrich had lived in a tent for two years while the castle was being built and lived in their desert fortress for only five years.

Today, Duwisib Castle belongs to the government of Namibia and it is open to the public as a museum. It has been beautifully restored and still contains many of the original furnishings. There is a wonderful campsite nearby, shaded by magnificent camelthorn trees.In the southern part of Namibia, on the edge of the desert, there is a once-large herd of wild horses that roam the plains. Several theories exist as to how this group of magnificent feral animals came into existence. One of these is that when the Von Wolf couple never returned to Duwisib, their select herd of horses wandered off into the desert. Nobody knows whether or not this is true, but it is a nice ending to a sad story!

Jack Barber and Sally Barnes (Mbotyi River Mouth)

As the story of the German officer, Major Hans-Heinrich von Wolf, ended in the bitter and brutal fighting of the First World War, the story of the South African, Private Jack Barber, was starting in the mud and horror of the trenches. Jack’s story began unfolding when he was wounded at about the same time that Hans-Heinrich was dying. He had played soccer for Scotland before the war, but had returned to South Africa. Then the war broke out, and he had volunteered to fight for King and Empire. Now he lay on a hospital bed, badly injured. While convalescing in the military hospital in France, he was cared for by a volunteer nurse from Boston, Massachusetts in the USA. Sally Barnes was a beautiful young woman who loved horse riding – but she loved people even more and was deeply compassionate about those who were suffering. When she heard about the awful wounds being inflicted on men in the filth of the trenches, she felt duty-bound to do something about it, and volunteered to go to Europe and care for the injured.

Sally nursed Jack back to health and the two of them, both shy, reserved people, felt a strong attraction for one another, but they could not bring themselves to confess their love! The war ended and Jack was repatriated to South Africa while Sally returned to Boston. But Jack had plucked up the courage to at least ask her for her postal address.

On his return to South Africa Jack decided to establish a trading store in a remote corner of the Union. The tribal area known as the Transkei Territory had few white people in it and those that were there were mainly traders. Jack was granted ownership of the Mbotyi River Mouth Trading Site by deed of grant of Crown Land. He built a little corrugated iron shop and lived in the back of it.

Mbotyi is an idyllic location, with a pristine expanse of beach, a lovely lagoon, rolling hills covered with one of the largest indigenous forests in South Africa and with the surrounding coastal escarpment cut by enormous gorges with spectacular waterfalls pouring into their depths. The marine cliffs too, that line long sections of the coast, are interspersed with waterfalls plummeting directly into the Indian Ocean. Not for nothing is this unspoilt paradise known as the ‘Wild Coast’. The breath-taking splendour and quiet surroundings were a comforting balm for Jack's damaged mind and gas-infected lungs after the ugly destruction and ear-splitting shelling of the war.

But Mbotyi is also very isolated. The nearest town, Lusikisiki, is about 30km away and back then it was no more than a collection of huts around a magistrate’s office and police post that also served as a post office. Jack, with his little trading store, offered the only place where locals could trade their goods (crops, hides, dried fish and flotsam and jetsam washed up along the coast) for blankets, clothing and small luxuries. And when the rains came, the track through the forest and up the escarpment became impassable, so goods could not be brought from Lusikisiki in the ox wagons, whence they had come from Umtata, the capital of the territory, some further 100km away.

It was a lonely life for Jack. But he had retained contact by correspondence with Sally, and the letters he received from her via the erratic postal service were the highlights in his life. Sally, fondly remembering the wounded man she had nursed in France, had never married. She kept herself busy riding on her beloved horses and doing charitable work amongst the needy in her city of Boston.

Jack longed to ask her to join him, but he just could not bring himself to tell her how he felt about her! What sophisticated American girl would give up her life in a cultured city to come and live in a remote corner of Africa where there would be no other white people?

In 1928, ten years after they had last seen one another, Jack finally took the plunge – he wrote a letter to Sally proposing to her! He didn’t really believe she would accept! Anxiously, he waited as the weeks and months rolled by – what would her reaction be? When the wagon from Lusikisiki finally lurched to a stop in front of his shop with Sally’s reply, he opened the letter with trembling hands . . . YES! She had accepted his proposal! She would come out to Africa and marry him!

Jack was ecstatic and over the next six months all the necessary arrangements were carefully made. Jack built a little cottage for them to live in – really no more than a beach shack! He bought a horse for Sally and prepared a little garden. Sally embarked from Boston on a ship bound for Cape Town and thence on another for Durban. Jack had calculated when the ship would be passing by Mbotyi and had told Sally to look out for a large bonfire, which she could expect a day before she docked in Durban. This would mark her new home. As the story goes, a massive bonfire was lit on the hillside above Shark Point on the designated day and Sally, standing excitedly at the rail, clearly saw it and waved frantically. Of course, the ship was too far off shore for either of them to be able to see one another, but one can imagine the emotions that the two of them felt. Jack thus welcomed his wife to be to her new home.

But from Durban Sally still had to get to Mbotyi. Motor vehicles were few and roads were atrocious, with many unbridged rivers to cross; but she eventually got to Lusikisiki and then travelled down to Mbotyi on the ox wagon. As it trundled down the steep, rutted track through the forest she caught occasional glimpses of the lagoon and the beach. It must have been awesome, and no doubt her heart was beating faster as they drew nearer.

There is no record of a description of their reunion, but one can imagine the excitement, the trepidation, the uncertainty and the joy. It was 1929 when Sally, the lady from Boston, finally arrived at Mbotyi by ox-wagon.

She would never open her trousseau and was never to leave Mbotyi. By all accounts, Sally was an exceptional woman. She fell in love with Mbotyi and led an active and involved life with the community. She nursed the sick and infirm and engaged in her passion: horse riding. She could be seen riding on the beach every morning. When he was not behind the yellowwood counter in his trading store, Jack was either fishing or walking the hills with his beloved pack of dogs. Strangely, he never wore shoes.

Like the Von Wolf couple, Jack and Sally had no children. They were quite content with their own company, living in harmony with the local people and the natural environment. The lady from Boston never returned to America. It is said that she would not even go to Lusikisiki – Mbotyi, Jack and the local people were all she wanted.

Sadly, the fairy-tale had to come to an end. Sally died in the late 1950s, having graced Mbotyi with her presence for almost 30 years, riding her horses nearly every day. Jack was devastated. He hit the bottle, went downhill rapidly and shortly afterwards his shack caught alight and he perished in the fire with his dogs. Some say he took his own life, but others say he simply died of a broken heart.

Today Mbotyi is still remote, but the roads have been improved somewhat and it is a lot easier to get to. It is a little-known holiday destination and there is a holiday lodge and a campsite where Jack and Sally once lived. The pathway leading from the front of the lodge to the beach is aptly named Sally’s Alley. It is all that remains to remind people of the romantic tale of these sweethearts who were brought together by the First World War. Nothing like the imposing fortress that stands on the edge of the desert in Namibia as the legacy of the couple whose romance was shattered by that same war.

Future meetings and field trips/ Toekomstige byeenkoms en uitstappe

The next regular meeting will be on Monday 14th January at 19h30 at the Eastern Cape Veteran Car Club in Conyngham Road, Port Elizabeth. The member’s slot will be used by Franco Cilliers who will talk about the Bloemfontein night tank shoot. The curtain raiser will be by Ian Pringle on the topic The Midlands Mounted Rifles clash with the Kritzinger Commando, and the main lecture will be given by Barbara Kinghorn on the subject of Durban’s Lady in White: Perla Siedle Gibson.

Matters of general interest / Sake van algemene belang

Members’ forum/Lede se forum

Tiaan and Leticia Jacobs,wie vir die volgende paarjaar in Kaapstad woon, wil graag hulle verbinding met SAMHSEC volhou. Tiaan het ‘n artikeloor die Tweede Wêreld Oorlog se krygsgevangene, Johan Herselman Goosen, ingestuur wat lede interessant sal vind. Dit is aan hierdie Nuusbrief aangeheg.

World War I Centenary Years / Eerste Wêreldoorlog Eeufeesjare

The Paris Peace Conference opened on 18th January 1919 and only came to an end on 21st January 1920 with the inaugural General Assembly of the ill-fated League of Nations. The Delegates came from 27 nations (many of whose presence such as Haiti was of dubious legitimacy) and five national groups which were for the most part ignored. Three major powers (France, Britain and the United States) dominated the proceedings.

The former Central Powers were not permitted to attend or address the conference until the conclusions on the Treaty of Versailles (with 15 chapters and 440 clauses) were reached and presented to them as a fait accompli. In Germany this was termed the Versailles Diktat. The general tone of the proceedings was one of vengeance and vindictiveness driven by France and Britain. Apart from assigning responsibility for the war, demanding reparations and placing both military and economic restrictions on the defeated powers, other topics addressed ranged from prisoners of war to undersea cables, to international aviation. The final act of the war however only took place on 24 The 18th January was chosen as a symbolic date with strong overtones of humiliation, as it was the anniversary of the proclamation of William I as German Emperor in 1871, in the Hall of Mirrors at the Palace of Versailles, shortly before the end of the Siege of Paris. It was also a significant day in German history being the anniversary of the establishment of the Kingdom of Prussia in 1701.

Thus were sown the seeds for the Second World War 20 years later.

Major engagements in Jan 2019

The British Campaign in the Baltic 1918–19 only got going towards the end of the war and was a part of the Allied intervention in the Russian Civil War. The codename of the Royal Navy campaign was Operation Red Trek. The intervention played a key role in enabling the establishment of the independent states of Estonia and Latvia[6] but failed to secure the control of Petrograd by White Russian forces, which was one of the main goals of the campaign.

Websites of interest/Webwerwe van belang

Classical History

Ancient Rome’s collapse is written into Arctic ice

Remembering

10 of the most touching and impressive war memorials In the world

Historic aircraft

List of surviving Focke-Wulf FW190s

Resource materials of military historical interest/ VIDEOS

Something with a difference!

Leaving aside its propaganda tone, this short video is about the remarkable mass production of the B-24 Liberator bomber.

Jonathan Ossher, who sent this in, adds the following note:

Members are invited to send in to the scribes, short reviews of, or comments on, books, DVDs or any other interesting resources they have come across, as well as news on individual member’s activities. In this Newsletter, there have been contributions by John Ossher, Barry Irwin and Tiaan Jacobs.

TAILPIECE:

Robinson Meyer The Atlantic: Science 15th May 2018

Holly Godbey War History Online 20th December 2018

Marla Brown Fogelman Tablet 9th November 2018

Bronmaterieel van krygsgeskiedkundigebelang

* The worst jobs in history: At sea (Navy Documentary) A 49 minute documentary looking at lousy jobs on ships

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V7ktD66YvJ0

* The B-24 Liberator Willow Run Assembly Plant

https://www.youtube.com/embed/iKlt6rNciTo?rel=0

“Production began here at Willow Run six months before Pearl Harbor! Henry Ford was determined that he could mass produce bombers just as he had with cars, so he built the Willow Run assembly plant and proved it. This was the world's largest building under one roof at the time. This film will absolutely blow you away – one B-24 every 55 minutes – and Ford had its own pilots to test them. And no recalls! Hitler had no idea the U.S. was capable of this kind of thing.”

“The long hanger at Willow Run, Michigan has a 90 degree turn in it so Henry Ford would not have to pay taxes in the next county. That short end is being saved and restored today as a museum. The big hanger doors are still operational after all these years.”

Chairman: Malcolm Kinghorn culturev@lantic.net Secretary: Franco Cilliers Cilliers.franco@gmail.com Scribes: Anne and Pat Irwin p.irwin@ru.ac.za

A fortress with a view: Hohenzollern Castle in Bisingen, Germany.

Photo by IlhanEroglu.