Newsletter/Nuusbrief 161

February/Februarie 2018

SAMHSEC’s January 2018 meeting took place on the 8th at the usual venue in Port Elizabeth.

The Members’ slot was taken by Andre Crozier on the subject of the recent book by Leopold Scholtz entitled Ratels on the Lomba – The story of Charlie Squadron.

On Saturday 3rd October 1987, while South Africans were going about their usual Saturday activities, several thousand kilometres away a clash of armour was taking place on a scale not seen in Africa since the Second World War.In August 1987 the Angolan army (FAPLA) was again advancing to the south and east with the aim of destroying UNITA for once and for all, this time with four Armoured Brigades equipped with tanks. This was too much for UNITA and the supporting 32 Battalion to handle.

As part of Operation Moduler, Charlie Squadron, part of 61 Mechanised Battalion, was deployed deep into Angola to block FAPLA at the Lomba River. Despite the obvious doctrine that tanks should fight tanks, Charlie Squadron, armed with Ratel armoured cars, led the attack against the Angolan 47 Brigade equipped with T54 and T55 tanks. The battle was fought at close quarters in thick bush and raged all day. At the end of the day, 47 Brigade had suffered such heavy losses in men and equipment that it ceased to exist as a fighting unit.

What is unique about this book is that Leopold Scholtz has told the story of a single unit, Charlie Squadron (ex 2 SSB in Zeerust). He interviewed many of the members and had access to their diaries. Charlie Squadron was not an elite professional unit but a unit composed, except for the Squadron Commander and Warrant Officer, of 19 year old national servicemen. However, they had been well trained and despite their inexperience performed exceptionally on the day. Charlie Squadron suffered only three casualties during the battle. A Ratel was hit by a ricochet from a T54 tank. The driver suffered a horrendous wound with a 500 gm piece of shrapnel lodged in his skull though his eye socket. He was evacuated to the border and from there to 1 Military Hospital in Pretoria where Professor Ian Copley, then serving as a neurosurgeon in the SADF, performed the operations that saved his life. After six weeks the soldier was discharged with a prosthesis hiding his wound. Ian has previously given the Branch a talk on this case. The book is recommended for anyone who would like to find out about this remarkable battle and how this unlikely group of soldiers changed the course of history. It lists all the members of the unit and makes one wonder how they fared in later life.

The curtain raiser, titled South Africa’s Mobile Watch Units: A brief history, was given by Franco Cilliers.

The Mobile Battalion was created on 28th December 1957 by the Union Defence Force.The unit was established at Potchefstroom with a strength 65 members as the Mobile Battalion of the South African Engineering Corps. The first officer commanding was Commandant P.F. van der Hoven, his second-in-command was Major C.J. Spiller. On the 11th July 1958 the unit was renamed The Mobile Watch. Their primary purpose was to provide a force for internal security duties and practical assistance to other government departments. A secondary purpose was to provide well-trained men who could be absorbed into other government departments or private organisations to train artisans or operators of heavy machinery.

The planned curriculum was as follows:

Exercise Steenbras entailed taking part in the opening of parliament, an anti-terrorism exercise and a trip on a Navy Minesweeper. One result of the anti-terrorism exercise was the decision to improve or redesign the army issued web gear.

Operation Kenhardt was a drought relief operation to assist farmers with relocating sheep to new pastures.The operation resulted in the movement of 30000 sheep from the drought stricken areas around Pofadder and Kenhardt to the area around Loeriesfontein and Carnarvon. The total sheep loss was only 0.03%.

Operation Winklak was also a drought relief operation to drill more boreholes and transport water for farmers between the Orange and Molopo Rivers. The area of the operation was 8 000km2. During the operation 5.6 million litres of water was transported to the farmers resulting in 207296km travelled by the vehicles.

2 Mobile Watch was established at Tempe base in Bloemfontein on 1stApril 1959. The unit had a Headquarters and three Squadrons (Engineering, Armour and Infantry). In July 1959 W.P. Louw was appointed officer commanding and Warrant Officer 1 Piet Grove as the RSM.

1960 saw active serviceby both units, such as Operation Duiker, the suppression of unrest in Nyanga and Langa townships, and the Pondoland Rebellion. In this case, a task force made of contingents from 1 and 2 Mobile Watch took part in the operation which was from 8th December 1960 until 17th February 1961. This was the first occasion on which helicopters were used for transporting troops on a large scale.

In December 1959 two additional Mobile Watch units were established in Durban (3 Mobile Watch) and Grahamstown (4 Mobile Watch). Each unit was established with 75 men which was later increased to 150 men. These two units never really got off the ground due to manpower problems. 1 and 3 Mobile Watch were merged in 1961 and moved to Kroonstad where the unit was renamed 1 Combined Construction Regiment in 1965. 2 Mobile Watch was transformed into 1 Parachute Battalion on 1 April 1961.

The main lecture, The Spanish Armada 1588 was presented by Ian Copley. Ian has submitted the following report on his talk which, at his request, has not been edited.

Having learnt to sail a small keel yacht one realises that a sail functions in the same way as a vertical aircraft wing and one can head into the wind to within a few degrees, the equivalent of the angle of attack of a wing.

Square-rigged sailing ships in the Reformation period had difficulty in achieving much more than 45° into the wind.

Mary Queen of Scots, Dowager Queen of France, was beheaded by her cousin, Protestant Elizabeth I at Fotheringhay Castle in February, 1587; she was first in line to the English throne since Elizabeth was childless. There was Catholic outrage in France, Spain, and Rome. A political climate existed also in England, between Catholics and Puritans since the queen’s father, Henry VIII, had been excommunicated and Papal control of the church eliminated. The Spanish army was in the Spanish Netherlands under the Duke of Parma against the Dutch Protestants. The English army had been sent to assist them in Flanders.

Like Phillip of Spain, Elizabeth exercised control over the English Navy.

Philip II of Spain had the first claim to the English throne after Mary being descended from Edward III. He did all the planning for the Armada from the remote Escorial near Madrid. Decisions and orders for Santa Cruz, and later Medina Sidonia, were sent directly to Lisbon or Cadiz as he was also king of Portugal. It was to be the largest fleet engagement in naval history.

For all square rigged ships of the time, it was dangerous to be caught on a lee shore giving them an option of anchoring or running aground and having to wait for a change of wind. In order to engage in battle with the advantage it was essential first to be up-wind of the enemy ships.

High fore and aft castles were useful in close encounter giving advantage to boarding and musketry. Thanks to John Hawkins’ designs some new naval ships were lower fore and aft, thinner and faster than a typical galleon and were more suitable for manoeuvring and long-range cannonade. They had a better weathering capability.

Supplies, in addition to powder and shot for cannons and small arms, came in barrels of seasoned water-proof wood that were used for the salt meat, salt fish, biscuits, water, and wine.

Unfortunately the quality of gun powder was variable, as were the exact sizes of cannon balls, affecting range and accuracy.

Sir Francis Drake’s anti-Spanish sentiment arose when his merchant ship was attacked in the West Indies in 1572 by the Armada of New Spain. He escaped, as did Hawkins who arrived later in Plymouth, the only two ships to return, causing their complete financial loss.

His first revenge came the following year when he captured a Spanish frigate and the brought home the ‘gold from the gates of Nombre de Dios’.

He made a circumnavigation of the world in the Golden Hind between 1577 and 1580, 50 years after Magellan.

The contributions of ‘el Draque’ to the difficulties in the formation of the Armada are less well known. His harassment of shipping, destroyed or captured, in the Atlantic contributed to scarcity of provisions and the barrel wood for provision storage. At the same time he diminished the Portuguese fishing industry that provided salt fish for the ships. Financial loss was incurred by the capture of a treasure ship worth the whole fleet.

At the same time Mediterranean ships were reluctant to sail West of Gibraltar, obliging troops for the Armada to march overland as well as reinforcements for the Netherlands.

As an adventurer privateer authorised by the queen, he was not officially a pirate. He did not suffer fools gladly, but looked after his ships and crew.

Drake’s activities resulted in the Armada to be delayed by a year.

He was a strict, Devonshire man [his father was a lay preacher]; everything was according to God’s Will. He was not popular with the nobility, but got on well with Elizabeth.

One of his most celebrated acts of harassment, to ‘singe the King of Spain’s beard’, occurred in April, 1587, when Drake was tipped off by two Dutch ships as to the whereabouts of the gathering Armada and so he sailed into Cadiz harbour, selected prizes and burnt the rest of the ships. The Spanish lost 37 ships and supplies including one great galleon. Opposition was mainly from galleys.

Drake was almost caught out when becalmed next day; his ships had to double anchor to turn for broadsides against the galleys that had manoeuvrability, but poor fire power.

An exchange of prisoners after salutation and gifts of wine from the governor of Cadiz was offered, but a sudden breeze altered the situation and he escaped to look for a Portuguese carrack from Goa sailing via the Azores he somehow had had news of. It was captured and taken it to England. This loss of gold, jewels and cargo worth £114 000 as well as the loss of ships was an important factor in the Armada’s delay in departure. Drake lost one prize ship and its new crew.

He then threatened Lagos and Sagres on the Portuguese coast, but whilst on land, he took the opportunity to service his ships – the cleaning, fumigating, rummaging. Sick crew were sent home in prizes.

The Duke of Sidonia Medina was put in command of the preparations for the Armada after the death of the famous Spanish sailor, the Marquis of Santa Cruz who had died of over work in trying to collect and victual the Armada as Phillip II was constantly sitting on their successive necks.

Lord Howard of Effingham was put in charge of the Navy by Elizabeth; he had the good sense to make Drake his Vice-Admiral [from the Arabic ‘Amir al Bahr’, ‘lord of the sea’].

In early 1588 an English fleet of 100 sail, also chronically short of victuals and ammunition was available.

Lord Seymour was at Dover with a fleet of 35 ships in case of invasion by Parma across the Channel.

Elizabeth had decided to commit 14 heavy galleons in a total of 50 ships including armed merchant men and volunteers. At last they were given permission to sail towards Cadiz.

The Armada left Cadiz at the end of May, 1588 and reached Corunna after 20 days.

In a howling gale from the South West some ships were damaged in the harbour. Those still at sea were scattered and damaged. Thirty ships were still missing with 6 000 soldiers. Many were ill with ship’s fever, scurvy and dysentery from spoiled food.

Medina became disheartened and reluctant. Phillip replied, “Forward in God’s name”. The fleet was delayed by a month giving time for repairs and some re-victualing. Hospitals were opened ashore for the sick that prevented an epidemic afloat. Most of the missing ships eventually returned accompanying two prizes.

On 21 July a favourable wind blew from the South. The North wind that had prevented the Armada sailing from Corunna had been favourable for the English fleet to sail toward Corunna. This change of wind then favoured of the Armada and the English fleet was obliged to return to Plymouth having incurred damage as well as shortage of provisions and sufficient ammunition.

After a period of calm, a gale scattered the Armada ships, but they eventually regrouped off the Lizard where repairs could be done in the meantime. Five galleys had been lost, including one of 30 guns.

On 29 July the Golden Hind, part of the screen, had sighted and reported Armada off Scilly Isles that proceeded to lie off the Lizard.

The legend exists that Drake was playing bowls on Plymouth Hoe – “We have time enough to finish the game and beat the Spanish too” – and for the tide to turn – probably apocryphal. The Spanish fleet would have had the advantage of wind and tide if Drake had ventured out sooner.

At the sound of the signal gun the Spanish formed their crescent with the largest ships at the centre and at the horns. This required skilled seamanship. Only the horns could be attacked. The English showed the nimbleness and speed in single or double line ahead.

The Spanish admiral hoisted his banner being the signal to attack whilst Effingham sent a pinnace with the challenge in medieval fashion.

Over 30-31 July the English fleet came out of Plymouth and then it separated into two groups for an attack. Drake in the Revenge tacked upwind to gain the rear of the Armada since leeward ships could only stand and fight, or run.

Sailing down wind of the Armada towards the open sea Effingham in the Ark Royal exchanged broadsides with ships of the northern horn.

Drake then assailed the Southerly wing of Portuguese galleons under Recalde; a long range cannonade of Recalde’s ship, San Juan, ensued until rescued by the San Martin. Short range and boarding was thus avoided, the Spanish having heavy, but short range guns.

Later two Spanish ships collided; the Rosario with the San Salvador followed by a huge explosion, one ship was left burning from an unknown cause.

The decision was taken for the Armada to anchor off the Isle of Wight and await news of a definite rendez-vous with the Duke of Parma. The occupation of the island as an invasion base was considered impracticable and they were too low on ammunition.

On the night of 1-2 August off Portland Bill the English fleet was in line astern of Drake’s Revenge that showed a stern lantern and was being followed by Howard in the Ark Royal, the Spanish having lost the weather gauge.

Next morning Howard found that he and two other ships had been following the poop lantern of the enemy flagship. He had to come about, but kept the Armada in sight. A Spanish opportunity to attack was missed.

There was no sign of Drake, he had, as an excuse, put out his light, then found and captured the Rosario that was the biggest and richest ship in the Armada. The captain surrendered his ship with 55 000 golden ducats and stores of arms and ammunition. The San Salvador was also found and stores taken; the ship was later towed into Weymouth.

The English fleet continued to catch up with Armada in calm weather Then, with an East wind blowing, the Armada was too far inshore to get to windward, so the Spanish tried to tempt the English to close and board, but this only developed into a long range cannonade.

In a separate engagement Martin Frobisher in the Triumph, the biggest ship of either fleet, with four merchantmen were unable to weather Portland Bill where they were obliged to anchor, only to be attacked by 4 galleasses.

They were unable to get free until the wind changed to the South and could then be rescued by Howard’s ships.

The San Juan, now repaired, needed to be rescued. The fleet had left the San Martin alone to face the English; she struck her topsails as an invitation to grapple and board; admiral to admiral. As before the English resorted to a cannonade; the San Juan took heavy fire. The English stood away as more Spanish ships ‘flocked together’ to defend their flagship.

During 4 – 6 August the crescent was reformed, after engagements off the Isle of Wight, with easier sailing in light winds and calms. Messages were sent to Parma to be ready to embark troops.

The English fleet followed warily; and missed a straggler that was towed away by galleys, and ships of the right horn. Small boats attacking it from Frobisher’s Triumph were beaten off by musket fire.

The English had inflicted heaviest losses until then, but there was no severe damage to either fleet considering the amount of powder and shot expended.

The English fleet was trying to nudge the Armada ships onto the coastal shallows and rocks [the Owers] further along the coat when a breeze started and the Armada was able to put out to the open sea and head for Calais.

Hawkins and Frobisher were knighted by Lord Howard.

Thirty-five sail under Seymour had been cruising between Calais and Dunkirk, up and down the Dutch coast looking for an invasion fleet.

The Armada was ‘saluted’ by a wind from the West and on 27 July arrived at Calais. They anchored suddenly, hoping the English fleet would sail past.

The English fleet with a total of 135 ships large and small anchored close by and were joined by Seymour’ patrolling fleet.

The Duke was not able to be near the Armada; there was no chance of a crossing to Kent. Seymour had noticed the small ships anchored under the cliffs of Calais that had been collected by Parma for the invasion, to be very inadequate. There was no sign of Parma who was then at Bruges.

A plan was made to use fire ships. Drake and Hawkins donated one each of 200 tons to make a total of 8 ships. At midnight on 27 July, 8 fire ships under full sail were dispatched only resulting in disrupting of the Spanish formation. No Spanish ships caught alight. The ships contained pitch, brimstone, and a little gunpowder, that being still in short supply.

The English ships were not ‘Hell-burners’ [full of gun powder] as thought by the Spanish, but the cannons were loaded and went off as they heated. The move was possibly anticipated by Sidonia Medina, as boats were made available to tow or allow the fire ships onto shore.

Half the Armada cut their cables and fled to regroup off Gravelines as the south-westerly wind prevented them from getting back to Calais, the remainder of the fleet could join them at Gravelines. They were fearful of the Dunkirk shallows further along the coast as the Dutch had removed the marker buoys.

Over the 6 and 7 August the English fleet to windward provoked fire but stayed just out of range and, after returning a long range cannonade, closed in with broadsides.

Many Spanish gunners were killed to be replaced by soldiers who were inexperienced. The Spanish hulls were vulnerable as they heeled over in the wind. A large galleass was chased aground.

By 8 August the Armada appeared to be on the point of defeat, but regrouped after a squall, followed by a South wind, allowed it to sail northwards avoiding the Dunkirk shallows and retire into the North Sea.

The Armada lost 5 big ships, many were damaged. Of these, 2 had run aground at Calais and the crew were killed off. Two galleons ran aground the next day near Walcheren and were captured by the Dutch. A carrack ran aground at Blankenburghe and another sank. All 155 English ships got underway with few casualties.

At last Sidonia Medina made the decision to sail for Spain keeping as far away as possible around Scotland and Ireland.

England still regarded the Armada as a danger to the country, but by this time the fleet was very low on food and ammunition. However, they followed as far as the coast of Scotland leaving Lord Seymour behind in case of an invasion attempt.

The Armada’s intended passage home was hazardous, and not having chronometers for longitude, they were unable to judge the effects of the Gulf Stream and westerly winds that brought them closer to the shores of Scotland and Ireland than intended. Many ships were vulnerable as they had lost their anchors having cut their cables at Calais.

After Gravelines may ships were badly battered. There were spoilt and lost stores, animals thrown overboard to save water, 3 000 personnel were sick beside those wounded. The shortage of water increased daily; ships sank, disappeared, or were wrecked.

5 000 men were lost by drowning, starvation or death on the Irish shore - 33 official executions by hanging were done as they were regarded as invaders.

A few wreck survivors were killed and robbed by Irish peasants; mostly they were helped after surviving shipwreck. Several hundred Spanish crewmen escaped to Scotland.

Forty-four ships large and small out of 130 returned to Corunna by 29 September including the Duke of Medina Sidonia’s ship. One ship sank on arrival and another ran aground due to lack of crew. Most ships were not fit for further service. Many officers and crew died, after their return, from disease and the effects of starvation. Medina survived to retire to his estates.

Future meetings and field trips/ Toekomstige byeenkoms en uitstappe

The next SAMHSEC meeting will be on Monday 12thFebruary 2018 at 19h30 at the Eastern Cape Veteran Car Club in Conyngham Road, Port Elizabeth. The curtain raiser will be by Andrew van Wyk on the subject of Cannonville. The main lecture will be by Pat Irwin on Muzzle-loading cannon.

Matters of general interest / Sake van algemenebelang

Special weekend for history buffs

Richard Tomlinson has brought the following event to our attention: A special Anglo-Boer War weekend, hosted by the War Museum in Bloemfontein and the Lord Milner Hotel, will take place at Matjiesfontein from March 16 to 18. The programme includes top speakers such as Tokkie Pretorius, director of the Anglo-Boer War Museum, who will discuss Soldiers of the Queen; Dr Johan Loock, who will review the famous and controversial Boer Commandant, Gideon Scheepers; Allan Duff, who will cover the activities of the commandoes of General Wynand Malan and Commandant Willem Fouche during the last week of the war; Dr Dean Allen will conduct a walking tour of the village and present Empire, The War and Cricket; and Dr Arnold van Dyk, co-author of Yeomen of the Karoo, will lead a special tour to Laingsburg and the nearby battlefield of Driefontein. There will be a visit to Monument Cemetery where Scottish hero, Major-General Andrew Gilbert “Andy” Wauchope, hero of Magersfontein, is buried. A star-gazing tour will celebrate the clear Karoo night skies and Johnny Theunissen’s Red Bus Tour, will be among the highlights. Accommodation is available at various village venues including the Lord Milner Hotel, where scrumptious meals will be served in the historic dining room. Costs range from R3860 per person, depending of the type of accommodation chosen.

Booking is essential – e-mailbookings@lordmilnerhotel.co.za. Quality accommodation is also available at nearby Laingsburg and on guest farms in the area.

For further enquires, phone 026 561 3011

Historic enquiry about Andrew Geddes Bain RobertGreig at greig.rj@icloud.comhas written to SAMHSEC enquiring whether anyone has information on a story which claims that Andrew Geddes Bain, road builder (including the Ecca Pass) and geologist who served during the Sixth Frontier War as a captain in the Beaufort Levies, was court-martialled for ordering an insurgent to be shot. If anyone who can assist Robert in his research, please contact him directly.

Individual members’ activities / Individuele lede se aktiwiteite

Richard Tomlinson and Pat Irwin have both had articles published in the latest Military History Journal (Volume 18 No 1), which should have reached members by now.

World War I Centenary Years / Eerste Wêreldoorlog Eeufeesjare

Major engagements in February 1918

No major land engagements took place during February 1918, but there was constant skirmishing and probing along the Western Front and, to a lesser extent, on the Austro-Italian Front. On the Eastern Front the German army was largely concerned with consolidation of its gains, including an offensive in the Baltic States, and some mopping up after the collapse of the Russian Army following the October 1917 Revolution.

On the naval front, a number of minor engagements took place. Although U-boat successes began to drop, particularly in the Mediterranean, they were still able to find and sink ships sailing independently. Allied shipping losses concomitantly continued to fall over the course of the year.

On 17th February all ships of the Russian Baltic Fleet were, due to the new German land offensive, ordered to leave their bases at Reval (now Tallinn) and Helsinki and to sail to the Russian naval base at Kronstadt. There they later played a significant role in the defence of Petrograd (St Petersburg). This came to be known as the Ice Cruise of the Baltic Fleet and involved vessels from battleships, icebreakers and gunboats to transports, minelayers and submarines, some 240 in all. Those that could not be moved were scuttled. All the evacuated ships had reached Kronstadt by 22nd April. Two air force brigades and large amounts of military equipment were also transferred.

The Allies’ continued attempts to block access through the Straits of Dover began to bear fruit in 1918 and by February, units of the High Seas Fleet including U-boats had abandoned the route in favour of sailing north-about round Scotland, with a consequent loss of effectiveness. An Italian attack on Austrian shipping known as the Beffia di Bucarri Raid is worthy of note. Penetrating what was considered an extremely safe harbour at Buccari (now Bakar in Croatia) fast torpedo boats unleashed six torpedoes of which only one found a target, slightly damaging a freighter. They then returned. Despite the lack of measurable success, the raid was a considerable boost to Italian morale which had suffered badly after the Battle ofCaporetto (see Newsletter 157), and a psychological blow to the Austrians.

Websites of interest/Webwerwe van belang

1066 +

The Bayeux tapestry shows Britain’s birth as a European nation

John Lichfield The Guardian 17th January 2018

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/jan/17/bayeux-tapestry-loan-britain-homecoming

Submarines/U-boats lost and found

Mystery solved as Australian World War 1 submarine found after 103 years

News 24 21st December 2017

‘The most intact U-boat wreck I’ve ever seen’ – The Discovery of U778

Innes McCartney Abandoned Spaces January 2018

https://www.abandonedspaces.com/uncategorized/most-intact-u-boat-wreck.html

World War II

US Army hero dog during WWII receives posthumous medal

News 24 15th January 2018

Hitler’s ‘Super Mercedes’ going up auction

Andrew Blake The Washington Times 16th January 2018

General Bernard Montgomery’s Rolls Royce Phantom III Sells for Much Less Than Expected

George Winston War History Online 16th Jan 2018

Falklands War

Falklands War 'true hero' Captain Rick Jolly dies

BBC World 14th January 2018

https://flipboard.com/@flipboard/-falklands-war-true-hero-captain-rick-jo/f-3a5951458b%2Fco.uk

Cold War and post-Cold war

The Kyshtym Disaster of 1957: The largest nuclear disaster we’ve never heard of

Martin Chalakoski The Vintage News 17th January 2018

Cyber warfare

Swarm of three remote-controlled drone boats attack Saudi-flagged oil tanker in the Red Sea

The following three URLs, all in open sources, examine the attack in the Red Sea last week.

Members are invited to send in to the scribes, short reviews of, or comments on, books, DVDs or any other interesting resources they have come across, as well as news on individual member’s activities. In this Newsletter, there have been contributions by Richard Tomlinson, Malcolm Kinghorn, Barry Irwin and Jonathan Ossher.

TAILPIECE:

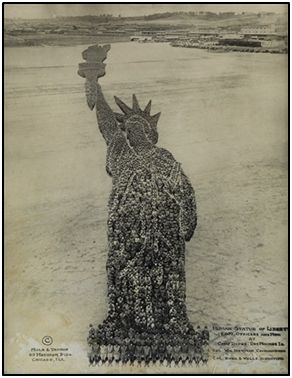

U.S. soldiers forming a giant Statue of Liberty figure. During the WW I years, Arthur Mole and John Thomas created some amazing images by using thousands of sailors or soldiers in uniform to create them. This picture, composed of 18 000 men in a training camp at Camp Dodge, USA was taken in 1918.

Sourced at:

Thanks to Jonathan Ossher.