Our speaker on 8 March 2018 was fellow-member Mr Ian van Oordt, whose subject was the run-up to the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805. This battle needs no introduction but, at the time for Britain, it meant a release from a life-and-death struggle for survival. It took place more or less in the middle of the period 1793 to 1815 known as the Revolutionary Wars and the Napoleonic Wars. The dividing point between the two came in the brief period of peace during which Napoleon became Emperor of France.

By 1804, France was all-victorious in Europe, defeating all opponents, and, in the process, building up a large empire. Britain still held command of the sea and was all that stood in the way of a French Europe. She had the naval power and the financial means to enable those defeated Western European powers to continue the struggle in Europe. In order for France to dominate the whole of Europe, Britain had to be conquered.

In 1802 Napoleon started to plan an invasion of Britain. He had the army but this had to cross the English Channel, so he started a huge expansion of his navy. Our speaker noted that the turning point of the Napoleonic War was the Battle of Trafalgar. Just as the Battle of Britain was the first screw in the coffin for Germany which set in motion its eventual defeat, so too was Trafalgar for the French.

The Napoleonic threat of invasion became for the British the most feared event and led to some of the most innovative and extraordinary ideas in an attempt to find solutions to the threat. Napoleon very early on recognised that the way to break Britain was through its overseas trade. He decided that the conquest of India would be far easier than a short-distance assault over the Channel.

Napoleon started the build-up to Trafalgar in 1797, when he was able to persuade the French government to accept his plan to invade Egypt with the intention of continuing the campaign into the East. Far-fetched indeed. At that time the British had been forced to remove their fleet from the Mediterranean. But late in 1797, rumours started to reach the Admiralty that the French were readying a fleet at Toulon and preparing to put to sea.

Vice Admiral Nelson was sent with a squadron to investigate, but a heavy gale delayed his arrival. Upon the British fleet's arrival at Toulon, the harbour was found to be empty - Admiral Breuys had sailed with his fleet. Nelson searched the Mediterranean and, at last, on 1 August 1798, he found the French fleet anchored in Aboukir Bay, Egypt, close to the shore with their sea-facing guns run out. Nelson attacked with some of his ships on the sea-facing side of the French and others on the shore-facing side. The French flagship blew up and all but two of the other ships were captured. These were taken later.

Britain realised that their Indian possessions were in danger via a land attack from Egypt and launched a campaign to take both Egypt and Malta. They succeeded in this in 1801, but the victory was too late to influence the peace treaty of Amiens in 1801. In 1802, hostilities started again and the French prepared plans for the invasion. An army arrived and was based from Boulogne through Flanders up to Vlissingen in Holland. They built large numbers of troop-carrying barges (rather like the Germans did in 1940). The Royal Navy applied its policy of blockading the French and Dutch ports. Napoleon now has the problem of clearing the Royal Navy out of the Channel for two weeks to allow the French invasion fleet to cross. In December 1804, Spain joined the French and declared war on Britain.

By January 1805 the invasion force was ready. Napoleon unveiled his first plan. His navy was scattered in all the major French ports along the Atlantic and Mediterranean coasts. Each squadron would break out of its port - hopefully undetected - and sail for Martinique in the West Indies, combine their forces, return to Europe, and join the Brest fleet. The Combined Squadron will then sweep aside the Royal Navy in the Channel Fleet and secure the Channel. On paper a good plan.

Napoleon issued orders to Admiral Missiessy at Rochefort and Admiral Villeneuve at Toulon. Missiessy succeeded in breaking out of Rochefort on 11 January 1805, but not undetected, and sailed for Martinique. Villeneuve broke out of Toulon on 14 January 1805 but a severe gale forced him to return to port because his sailors could not handle the overloaded ships. The British response to Missiessy's sortie appeared disjointed as they were not sure in which direction he had sailed - to the East Indies or the West Indies? As the two fleets did not meet, Missiessy returned to Rochefort. Was there confusion among the British? No. They were applying their "Blue Water" policy. This was a strategic sea defence system where the main battle fleet was divided into squadrons each responsible for a particular area. Some watched French ports and others, such as the squadron in the Western Approaches, did not. When a French squadron broke the blockade, all or part of the blockading squadron would disperse to search for the French. The Admiralty would be warned and, if deemed necessary, the non-blockading squadrons would assemble to defend the approaches to the Channel.

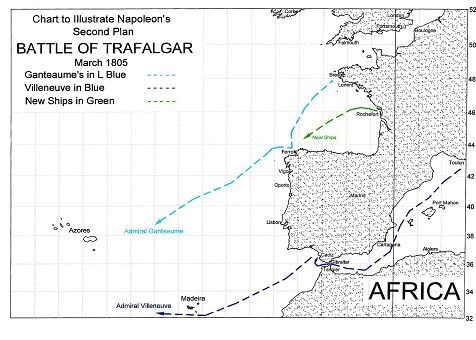

Napoleon concocted a revised plan which included his new ally, Spain. Again he hoped that the various breakouts would disperse part of the British fleet. Villeneuve was to break out of Toulon, head for Cadiz, drive off the blockading force and release the Spanish fleet. Together they would head for Martinique. Admiral Ganteume was to break out from Brest, pick up the Spanish fleet at Ferrol and meet up with Admiral Villeneuve at Martinique. Two newly-built ships would break out of Rochefort and head for Martinique.

Villeneuve broke out of Toulon on 30 March 1805, arriving at Cadiz, where he drove off Vice Admiral Orde's squadron. The next morning the combined French and Spanish fleets (the latter under Admiral Gravina) headed for Martinique. The new French 74s, Algesiras and Achille, escaped from Rochefort on 1 May 1805 and joined with Villeneuve at Martinique. Villeneuve waited at Martinique for Ganteume until a pre-determined date and, on 5 June 1805, he returned to Europe with his combined fleet.

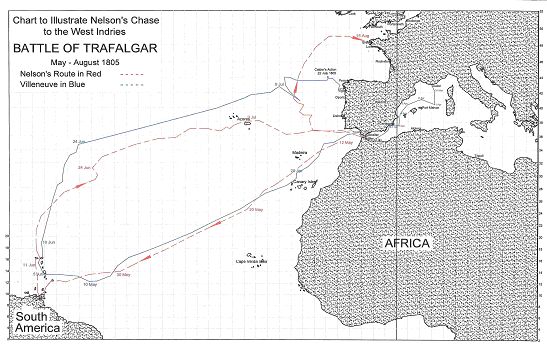

Nelson was informed of the Villeneuve's breakout from Toulon and assumed that he was heading for Egypt. He carried out a careful search of the Eastern Mediterranean. With no sign of the French, he headed for Gibraltar, where he was informed that the combined fleet had left Cadiz. After checking that the combined fleet had not gone to Ferrol, he correctly assumed that they had gone to the West Indies and gave chase. He arrived in the West Indies to be informed that the French and Spanish had left. After sending a Brig back to England with the latest intelligence, Nelson returned to Europe, where he headed for Gibraltar and then on to Brest, arriving there on 15 August 1805.

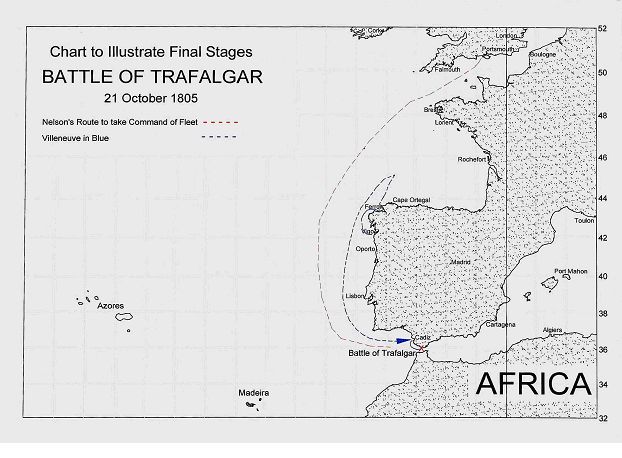

On his return to Europe, Villeneuve had gone to Ferrol to obtain provisions. Here he met with Admiral Calder's fleet. On 22 July 1805 in a fog-bound battle, neither fleet gained the upper hand with the French losing two ships. Others were damaged so he returned to Vigo for repairs. The facilities there were not extensive so, on 31 July 1805, the combined French/ Spanish fleet headed for Corunna (near Ferrol), reaching there on 1 August 1805. He continued northwards and, on 13 August 1805 just north of Cape Ortegal, one of his frigates intercepted a Danish merchant ship. Here Villeneuve learned that this ship had been boarded by a British ship of the line, HMS Dragon, whose captain mentioned that a British force of 25 ships of the line was nearby. In the late afternoon Dragon was sighted. Soon after sunset, Villeneuve did an about turn and headed south for Cadiz reaching there on 20 August 1805.

Nelson had returned home for a well-earned rest. His squadron was now blockading Cadiz and, on 15 September 1805, he rejoined them in his flagship Victory. On 19 October 1805 the Combined Fleet with 33 ships of the line under Villeneuve left Cadiz for their fateful meeting with Nelson's fleet at Trafalgar. The result was a complete victory for the British, the death of Nelson and the creation of the world's mightiest naval power for the next century. Most of the French/Spanish ships that escaped from the defeat were later captured as well.

While the combined fleet was heading back and forth between Martinique and Europe's Atlantic seaboard, a British force of transports with a small escort of warships was heading south to take the Cape from the Batavian Republic. Only some 30 miles separated this force from the combined fleet one night. The troopships avoided destruction. Had they been destroyed, we would possibly still be speaking Dutch in South Africa today.

What would have happened if Villeneuve had defeated Nelson's fleet on that fateful day in October 1805? Could the blockaded French and Spanish ships have joined Villeneuve and would the combined force been able to defeat the Channel Fleet, thus enabling Napoleon to cross the Channel and capture Britain?

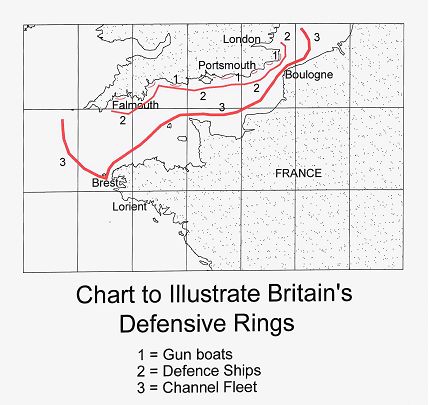

The British defence system for the Channel was complex. The first line was the Channel Fleet which for this discussion we assume to have been lost. The second line was a force of armed coastal defence ships stretching from London to Plymouth, including some of the lighter naval vessels like sloops and brigs. The third line comprised a force of sail- and oar-powered shallow draft gunboats to break up assault forces on the beaches. Many of these were armed with carronades - powerful short range guns which would have been deadly at short range. Nelson was asked whether he thought that the French could invade Southern England. His answer was "they can but not if they come by sea".

France had assembled an invasion force of 110 000 of their finest troops. Their force was well-trained and -equipped, confident of victory, disciplined and experienced. They had defeated the best armies in Europe and were led by excellent officers under the command of their Emperor, arguably one of the finest military commanders in history.

What would they have faced had they succeeded in landing most of that force? The British regular army in Britain had risen from 81 000 in 1801 to 103 800 in 1805. Some of these (15 000) were members of the Militia transferred into the army. At the start of the Revolutionary War, the British Army was poorly trained and ill-equipped. In 1794 General Dundas had started a programme of reforms and by 1800 these were bearing fruit. Training had improved and equipment standardised. They were not organised as efficiently as the French with the battalions grouped into brigades, divisions and army corps but new methods of fighting were incorporated in early 1800. These were designed to counter the lavish use made by the French of skirmishers and light troops and involved the creation by the British of light infantry and units equipped with rifled weapons - i.e. not smoothbore muskets.

The artillery had been reformed and new guns and howitzers with vastly improved ammunition designed by Desagliers, Thomas Blomefield and Shrapnel had turned the British guns and ammunition into world leaders.

The whole of Southern England was divided into districts or blocks which were supported by the Militia, who numbered 150 000 for the whole of Britain. All of the beaches in Southern England were analysed. The information required was the type of beach, access to the beach from sea and land and an estimate of the number of troops required to defend the beach. Our speaker has a picture of such a document.

Napoleon planned to advance on London after landing but he would have to subdue the rest of the country. The main manufacturing centres for Brown Bess muskets were London and Birmingham. Over 2 million of these were built between 1793 and 1815. In the years 1804 to 1815 Birmingham produced 705 000 to London's 176 000. This means that, if London came under French control, the government would move further inland and the war would continue.

The invasion boats were open boats, sail- and oar-propelled, and would require about two days to cross the Channel. 600 boats were available and 1 100 were needed. So each boat would have to cross, return, reload and cross again. The weather would play an important role, with the wind direction and speed being suitable for the crossing. Tide heights in the English Channel vary considerably, thus requiring the boats to arrive at a particular beach at a particular time which, with sail driven craft dependent on wind conditions, was impossible to guarantee. So the invading forces would arrive piecemeal and it would be easier for the defenders to oppose the invaders. Napoleon thought that crossing the Channel was rather like crossing a large river. This was a big mistake, made by another certain gentleman in 1940.

Only certain beaches on the English coast were suitable for the landing of heavy equipment such as artillery. These were heavily defended by gunboats and Martello towers. All harbours were heavily defended.

The day the invasion started would bring heavy congestion at all French and Dutch ports and harbours. The Royal Navy would launch every ship it had in attacks on the crossing forces and the harbours from which they came. Fire ship attacks on the latter would be launched and the French Army would suffer heavy losses even before they landed.

The last and most important defence that Britain had against invasion was the Foreign Office. This had been active, behind the scenes and under difficult conditions, negotiating with Austria and Russia. These negotiations resulted in the Third Coalition between Britain, the Holy Roman Empire (Austria and a number of lesser German principalities and states) and Russia on 1 July 1805, when the treaty was finally ratified and signed. By the date of the Battle of Trafalgar, all treaty members were amassing their armed forces on France's eastern and southern borders. This would have resulted in Napoleon fighting on at least two fronts had he continued with his invasion plans. This he did not want to do so, and, some months later, his army opposite England broke camp and headed for Central Europe to face the Coalition forces there. Note too, that, in 1808, the Iberian Peninsula became the scene of the Peninsular War of 1808 to 1814, a further front. The peninsular war in time became a war of attrition and a huge drain on men, material and resources, so much so that Napoleon in despair referred to it as the "Spanish Ulcer".

Mr van Oordt ended with one of Napoleon's maxims -

Of all the obstacles to the march of an army, the most difficult to overcome is the desert, mountains come next and large rivers occupy the third place.

Our speaker added to this maxim the comment that "he left out that little ditch called the English Channel, which was impassible". Napoleon made the mistake of assuming that the English Channel was a larger river.

Our Chairman thanked Mr van Oordt for his fascinating and well-researched talk and presented him with the customary gift.

NEWSLETTER NO 462 - MARCH 2012

Our speaker on 8 February 2012 was fellow member Mr Marius van der Merwe, whose topic was the evolution of submarines from ancient times to the American Civil War. His talk was well illustrated with a power point presentation.

In modern times submarines are defined as vessels that can travel both on the surface of water or be submerged and navigated under water for protracted periods by means of controlled buoyancy, have their own means of propulsion controlled by its crew independently of external factors, are navigated by the crew and have the means to resurface without external help.

Civilian submarines are used, inter alia, for marine science, undersea exploration and archaeology, facility maintenance, salvage and undersea cable repair and tourism. Criminals use them for smuggling contraband and for piracy.

Military submarines are built for warfare and are armed with a variety of weapons. They are used to attack and destroy ships and land installations, to patrol the oceans and to launch long range missiles.

Some are not able to operate independently but are attached to a mother ship by cable. These are submersibles and can dive to great depths. They have reached the deepest known point in the ocean, some 11 km below sea level. There are also Marine Remotely Operated Vehicles. These are used in waters too deep or dangerous for divers and are attached to and are controlled from a mother ship by a cable providing power and communications.

A wet sub is an underwater vehicle that does not have a hull for the crew. These are used for laying mines, intelligence gathering in harbours or for attaching listening and recording devices to underwater cables. These are deployed from a service ship or a specially outfitted conventional submarine.

The military uses of submarines are many and varied. A military submarine has a watertight circular steel hull of great strength to withstand high pressure when submerged. It has ballast tanks which are filled with water to make it submerge and which are refilled with air to displace the water and to bring it back to the surface. Its power plant must be able to operate without a constant supply of air when submerged. It may have separate power plants for use underwater and on the surface. It will have a rudder for directional control, horizontal hydroplanes for longitudinal control, effective weapon systems and electronic systems and have enough space for its crew and their supplies.

The history of submarines, or submersibles, goes back to 1300BC but it is not known whether much of this early history is fact or fiction. Persian divers at that time were using diving goggles with lenses made of the polished outer layer of tortoise-shell. In the Ancient Greek and Roman era, divers used the hollow stems of plants or reeds to breathe while swimming underwater. Herodotus records that, in 480 BC, a Greek named Scyllis was taken prisoner by Persian King Xerxes. He escaped and cut the moorings of the Persian ships before swimming 15 km to warn the Greek fleet of an attack. The result was the Battle of Salamis. In the 4th Century BC Aristotle records the first use of a diving bell. Alexander the Great (336 - 323BC) is supposed to have used a glass diving bell for reconnaissance in the Mediterranean.

In more modern times Leonardo da Vinci (1452 - 1519) in 1515 issued plans for a "ship to sink other ships". In 1535AD, Gugliemo de Lorena created and used the first modern diving bell for salvage operations. It was fitted with a valve at the top to release expelled air.

In 1578, the English mathematician William Bourne published a book "Inventions or Devises", in which he described a plan for an underwater navigation vessel known as Devise No 18 - a wooden-framed, enclosed craft covered in water-proofed leather. He suggested two methods of sinking and surfacing his vessel. One was to vary its volume by using flexible leather bags attached to the sides of the vessel. These could be adjusted to increase or decrease the volume of water in them so as to adjust the buoyancy of the craft. The other was to vary its weight by using ballast tanks.

In the 17th century, Ukrainian Cossacks used river boats called Chaikas that could be overturned and submerged. They were used for infiltration and reconnaissance. The crew was able to breathe the air trapped in the hull. They moved the boat by walking on the river bottom. Weights were used to aid the submerging process and pipes were used for additional breathing purposes.

Chaikas were between 18 and 20 metres in length, 3 to 3.5 metres in width and 3.5 to 4 metres in depth. The bottom of a chaika was carved out of a single tree trunk, with sides built of wooden planks. Reed bales were tied to the gunwales of the boat to protect it from sinking or enemy gunfire. They had two helms so never needed turning around to change direction. They carried 50 - 60 men and up to 6 falconets (small cannon).

Cornelis Drebbel (1572 - 1633), a Dutch engineer in the service of King James 1 of England, invented, built and successfully tested the first semi-submersible vessel, which was a decked-over rowboat. Three were built and tested between 1620 and 1624, reaching a depth of 12 to 15 feet. Floats with attached tubes brought air from the surface to the crew and the boat stayed underwater for 3 hours. Oxygen was created with saltpetre to refresh the air and measured depth using a quicksilver barometer. It had six oars and carried 16 people.

Drebbel invented the first compound microscope and the thermostat and built telescopes. The quality of his scientific knowledge was way beyond what mainstream science was thought to have been capable of at that time.

In 1634, two French priests, Mersenne and Fournier, set out proposals for a submarine with a design which could have described a World War 2 submarine. In 1653, Louis de Son designed a semi-submersible battering ram, propelled by a clockwork-driven paddle-wheel, which was not power-full enough to drive the vessel underwater. He was followed by many other inventors in the 17th and early 18th centuries. Nathanial Symons in 1729 built the first known example of ballast tanks, made of leather bags which could be filled with water and emptied while underwater.

David Bushnell (1740 - 1824), an American inventor, designed and built the Turtle in 1775, using water as ballast and manually operated screw propellers for propulsion. This was used to attack the British 64-gun ship of the line HMS Eagle in New York Harbour on 7 September 1776, but could not attach a mine to Eagle's hull. Regarded by some as the first true submarine, it was the first to be fitted with many of the devices later fitted to "real" submarines, including ballast tanks and pumps, propellers, devices for underwater navigation, course and depth control, lighting, snorkels and ability to carry weapons.

Bushnell turned his attention to torpedoes and floating mines, became a medical doctor and moved to France in 1787. Robert Fulton (1765 - 1815) was an American inventor and engineer who designed and built a workable submarine, the Nautilus, while living in France. This became the prototype for all further submarine development for the next century. This was tested in France. It was powered by two rowers on the surface and two men using cranks underwater. The cranks powered a propeller which was four-bladed.

Nautilus had a teardrop-shaped hull built of iron and copper with a round observation dome. The hollow keel was the ballast tank emptied and filled as required and had two horizontal fins or diving planes, as well as a snorkel covered in waterproof leather, allowing fresh air into the vessel while submerged. It was powered by a collapsible sail on the surface and a hand-cranked screw propeller when submerged. Its weapon was a mine which would be attached to the target ship. Napoleon was not impressed and, in 1804, he started to build submarines and other weapons for the British. In 1806, he returned to America and started a successful career building steam-powered (paddled) river boats. He died in 1815.

Karl Andreevich Schilder (1786 - 1854) was a Russian Lt Colonel of Engineers who built the first all metal submersibles. These were built of boiler iron with two conning towers, ballast tanks controlled by pumps, a fish-tail rudder, periscope and snorkel. It was powered by a removable mast and sail on the surface and four special oars when submerged. Its armament was a harpooned mine. It worked well but was too slow.

We come now to the 19th century and Dr Antoine Prosper Payerne, a French medical doctor and inventor (1806 - 1886), whose early work revolved round improving the oxygen content of air in confined spaces. He later designed diving bells and submersibles which were successfully used in marine salvage work. He invented the airlock, which permitted divers to exit and re-enter the bell, using compressed air to stop water from rushing in when the outer hatch was opened.

Wilhelm Bauer (1822-1875), a Bavarian, designed and tested the first German submersible, der Brandtaucher. This was during the German/Danish War for Schleswig Holstein. His design was rejected by the military bureaucracy but, with the help of Werner von Siemens, he built a working model and in 1850 was able to build a full scale submarine. This would launch 50 kg mines which would rise and attach themselves to the target. The Brandtaucher would then ignite the mines from a safe distance. It was propelled by two sailors turning a big thread wheel driving a propeller.

Bauer did his own testing, which proved to be dangerous. On two occasions his submarines sank and he and his crews escaped death by exiting through air locks. The Germans stopped bankrolling him and he moved to Russia, where he built his second submarine, the Seeteufel. This made 133 successful dives before sinking. Bauer and his crew made their second escape. He died in Munich, a broken man because he could not raise funds to finance his ideas. The pioneers coming on after him all drew inspiration from his efforts.

The American Civil War of 1861 to 1865 inspired many designers to give effect to their ideas. Both North and South used submersibles. The North used submersibles to clear harbours and the South to break the blockade enforced by the North.

A Frenchman, Brutus de Villeroi, built a salvage submersible but this was confiscated by the police during a salvage operation on the Delaware River. It was purchased for 14 000 dollars by the USN but never commissioned as it was "illegal", but it was the USN's first submersible. It had a diver's lockout chamber and on board compressors for air renewal and diver support. It sank in bad weather in April 1863.

The Confederates authorised civilians to build and operate ships as "Privateers". A New Orleans consortium led by Horace L Hunley built a 20 foot submersible with a three man crew (one to steer, two to crank the propeller). It worked but was sunk when the US Navy captured New Orleans. The Confederate Navy built a further 20 submersibles during the war, some steam-powered and others operated with hand-cranks.

Hunley's consortium moved to Mobile, Alabama and built more submarines there. A torpedo boat, the CSS David was built as a private venture by T Stoney at Charleston South Carolina. It was propelled by a steam-powered propeller and operated as a semi-submersible with ballast tanks.

It was used in action but only managed to damage some Union ships. Hunley's last submersible was named CSS H L Hunley and this sank the USS Housatonic on 17 February 1864. It was the first submersible to sink a ship in action. It also sank with all hands in the same naval action.

An experimental hand cranked submarine, designed by Scovel Sturgis Merriam was built by Augustus Price and Cornelius Scranton Bushnell in 1863. It failed its tests but the American Submarine Company was formed the next year by Price and Bushnell.

Few submarines and submersibles were built in the years after 1865 as the problems faced in designing and building a functional and operational submarine which could operate safely underwater had not yet been solved. The weapon systems in use were inadequate and often dangerous to the operators. Propulsion systems were not adequate. However, problems relating to trim and stability through buoyancy control had advanced to a relatively advanced state, as had hull strength and air supply technology. The next 40 years would see rapid development. But all this is for a future talk.

Mr van der Merwe's talk referred to many more designers and visionaries beyond those discussed above but we are limited to a set number of pages.

To conclude: - All ships can sink, but not all of them can resurface by themselves - Few ships are designed to sink-some need our assistance in this regard

Our Chairman thanked Mr van der Merwe for an interesting and well-researched talk and presented him with the customary gift.

NEWSLETTER NO 461 - FEBRUARY 2018

Our speaker on 18 January 2018 was Mr Jim Harwood, whose topic was the SADF attack on Cassinga on 4 May 1978. Cassinga was a mining town in Angola some 260 km north of the then South West African border.

Our speaker was, at the time, a Second Lieutenant commanding a platoon in 1 Parachute Battalion and took part in the attack in that capacity. He introduced his talk by explaining that SWAPO claimed that Cassinga was a refugee camp for 600-700 refugees whereas the SADF believed it was attacking a PLAN headquarters and logistics base. Mr Harwood pointed out that the people at the "refugee camp" were able to pin down the SADF for about five hours using anti-aircraft weapons and other weapons.

Our speaker said that he had always believed that his wife was the first person outside the SADF personnel to learn of the attack on Cassinga. She had heard the news from a friend who had attended an Editor's briefing which had been told that the SA forces had invaded Angola that morning. However, both Col Breytenbach and Maj Gen Phillip Pretorius had made similar claims. The secret was well-kept and certainly surprised SWAPO - and South Africa. He then briefly discussed the UN Resolution 435.

Why an airborne attack? He explained that a vertical envelopment - outflanking the enemy by going over his head - was the only option at Cassinga because the base was too far from the border for a conventional mechanised force to attack without alerting the enemy and risking heavy casualties. It had been postponed earlier and our speaker remembers wondering whether it would be postponed again while he was in the aircraft on its way to Cassinga.

The plan was to attack the parade ground at Cassinga at 0805, when the troops would be attending the morning parade. The SAAF used Canberra and Buccaneer bombers which dropped a mixed load of high- explosive bombs and small, round, rubber-coated bombs which were designed to bounce and explode at waist height. These were originally dropped from choppers (helicopters) and had been originally developed by the Rhodesians - and were very effective anti-personnel weapons.

The SAAF arrived on time and dropped their loads on target. Some of the bomblets detonated too quickly but most worked as designed. The attack was successful and left the parade ground covered with many dead and wounded. The survivors, both wounded and unwounded were left in a state of shock. The PLAN Commander in Chief, based at Cassinga, fled and remained missing all day.

The Buccaneers used WW2 ordnance which made a great deal of noise and destroyed a number of buildings, but left large craters used to good effect by the defenders later. Their most important target was the HQ complex which had not been identified by the photographic interpreters and so was not attacked.

The paratroops were carried in six SAAF C130 Hercules and C160 Transalls and arrived on time. Commanded by Col Jan Breytenbach, they numbered only 370 men, the maximum number that could be evacuated by the 19 SAAF Super Frelon and Puma helicopters operationally available.

This part of the operation was marred by a number of critical mistakes made by Military Intelligence and the SAAF. The aerial photographic interpreters mistook the height at which the photographs of Cassinga were taken. They used the wrong scale and miscalculated the distances on the ground. As a result the transport pilots dropped their paratroopers in the wrong places. In addition, the photographs had been taken during the dry season but the Calonga River was now full and fast-flowing. Some paratroopers were dropped on the wrong side of the river as a result.

When Col Breytenbach landed, he found that his men had not been dropped correctly; he promptly improvised accordingly and swung the plan of attack round from south to north.

Mr Harwood described his parachute descent and how he had steered his parachute away from the river, landing in waist-high elephant grass. His canopy covered his face and for a while he was tempted to just stay there. His description of what then ensued was based on his personal experiences.

He explained that the SADF expected a paratrooper to fold up his parachute and bring it back with him. Somewhat impractical, when he was already carrying a heavy weight of ammunition and other equipment and going into combat. This was an order ignored by the troops. He described the smell of cordite, the noise of weapons being fired and noted that some of these were heavy weapons - 14.5 mm anti-aircraft guns and even 23 mm guns. Some of these had been firing at the aircraft and the dropping paratroops, who noted bullet holes in their parachutes. SWAPO had not had much training in anti-aircraft shooting. Enemy snipers were shooting from trees and elsewhere and had to be taken out. He described his surprise when an enemy soldier who surrendered turned out to be a woman. Other women encountered later were made of sterner stuff and fought to the death.

In the enemy vehicle park a bus marked St Mary's Mission was found. This had been hijacked with a load of children and taken to Cassinga. Some of these later pleaded with the South Africans to take them back to South West Africa.

Our speaker explained that his platoon was pinned down by fire from the enemy trenches which were strongly held and in very flat ground. A number of officers had come along "for the ride". One of these was Major Hannes Botha, who had been Mr Harwood's training officer some 12 years earlier. He did not have the red dot indicating an operational jump opposite his name so had come to earn one at Cassinga. Our speaker described him as wandering around "like Audie Murphy", an American war hero who later became famous as a Hollywood actor in Westerns. He was not wearing operational kit and was everywhere getting in the way. (Author Willem Steenkamp, in his eloquent way of speaking, interjected a rather risqué Afrikaans saying in his typical Namaqualand drawl, pertaining to such a character of a superfluous nature, which had the audience in stitches before our speaker could continue.)

Our speaker explained that South African Paratroopers were initially not able to attack tanks. Most fortuitously, the captain of a Greek freighter transporting weapons from Cuba to Mozambique drifted into South African waters and was taken to Durban. Its hull and cargo were examined and the weapons were confiscated. A great number of RPGs (Rocket-Propelled Grenade Launcher) were among the cargo and these were put to good use by the SADF at Cassinga. The Russian instructions on the RPGs warned that they should not be carried by paratroopers. The SADF paratroopers chose to ignore the risks of jumping with such hazardous weapons and succeeded in landing safely with them by following the advice of an instructor, carrying them in the top part of their webbing where one can safely carry even a bottle of whisky, according to Mr Harwood.

The RPGs undoubtedly saved the South Africans from suffering heavy casualties when they were attacked by enemy tanks immediately before their extraction at the end of the operation.

Our speaker next described the very effective manner in which the 14.5 mm anti-aircraft guns were used in a ground role at Cassinga and the great gallantry of the enemy personnel who manned them, despite the heavy losses they suffered. If the gunners became casualties. The crew never hesitated to remove the bodies of their dead comrades and carry on firing the guns. He noted that Cassinga contained a faction of anti-establishment SWAPO cadres and believes that they were the heroic gunners.

He mentioned Lt Rick Venter who succeeded in firing his mortar effectively in spite of not having a base plate. It took a long time and much hand to hand fighting to clear the enemy trenches. Many of our soldiers distinguished themselves during this phase of the operation.

Our speaker then described the role played by Brig Martinus du Plessis in the operation. As Col Breytenbach had been appointed commander of the operation, there was no need for the brigade commander to be there. He took over Col Breytenbach's signaller with his radio. This was the only radio able to communicate with the operational HQ at Ondongwa. He took it upon himself to order the helicopters to start evacuating the troops prematurely even though the capture of Cassinga had not been completed.

When the extraction helicopters arrived, out climbed another visitor - Lt Gen Constand Viljoen, Chief of the Army, wearing his general's beret with full insignia. This prompted a somewhat presumptuous soldier to say to him "general are you mad? Take off your rank badges". (The original Afrikaans version was a lot more brusque and to the point.) The general, however, took the rebuke in the right spirit, and obeyed with alacrity.

The personnel extracted first included the sappers, whose demolition work had not been carried out, and the wounded, which were taken to the SAAF helicopter holding area in Angola, where there were no medical facilities. In the original plan they should have been taken back to SWA directly.

The Cubans and Angolans at Techamutete had heard gunfire and explosions coming from the direction of Cassinga and were on their way to investigate. Fortunately for the South Africans, the local commander had to wait for permission from the Cuban general in Luanda and this took some time. The SA Delta Company whose main role was to support the anti-tank platoon in the event of such an intervention, were among the first troops to be evacuated on du Plessis' orders. About 200 South Africans remained. The helicopter extraction had been carefully planned with troops allocated to specific helicopters, but Brig du Plessis' intervention had turned it into a shambles.

The danger facing the remaining South Africans was increased when the anti-tank platoon was ordered to withdraw from its position a kilometre south of Cassinga to one just outside the base.

Our speaker described the destruction of the enemy magazines, munitions sheds, etc., which had to be done with hand grenades as the sapper demolition teams had been extracted prematurely. He recalled a colleague who had dropped with a land mine. This he buried in the road in the path of the oncoming enemy tanks. The mine and the RPGs did excellent work, but it was the SAAF that saved the day.

Col Breytenbach had requested air support from Ondangwa and two Mirages were scrambled. A Buccaneer flown by Capt Dries Marais was diverted as well. After an unsuccessful attack by a Mirage on a tank, Capt Marais suggested that the Mirages should concentrate on the BTRs. This proved highly successful and 2 trucks and some 16 armoured personnel carriers were destroyed before the Mirages had to return to Ondangwa to refuel. Capt Marais shot up an anti-aircraft gun and ran out of ammunition. He then flew very low over the tanks and terrified their crews to the extent that they bailed out and fled into the bush. His aircraft had been hit 17 times but he safely got back to Ondangwa and was awarded the Honoris Crux, South Africa's highest award for bravery in the face of the enemy.

Thanks to the SAAF, the paratroopers were all, with the exception of five men, extracted safely. Major Church by chance saw one of the five and returned, landed and loaded all five. One of the helicopters had an extremely close shave when it avoided being hit by shells passing both above and below it.

The aftermath of the operation was a disappointing anti-climax. Instead of being congratulated on their highly successful operation and their gallantry, the men were asked what they had brought back with them as souvenirs. These had to be handed over. Our losses were four killed, one MIA (missing in action) during the landing and twelve injured. SWAPO casualties are not known.

Some while later, the men who took part in the battle were invited to a party at which they were able to talk informally to generals Magnus Malan, Chief of the Defence Force, Constand Viljoen, Chief of the Army and Bob Rogers, Chief of the Air Force, and tell them about their experiences at Cassinga.

The distinguished military historian and internationally renowned author, Maj Willem Steenkamp, recalled his own research on the battle and delivered an eloquent vote of thanks to the speaker. The Chairman then presented Mr Harwood with the customary gift.

ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING

Please note that notice was duly given fourteen (14) days in advance of the Society's Annual General Meeting (Cape Town Branch) to be held on Thursday, 12 April 2018, at 20:00.

FORTHCOMING MEETINGS

THURSDAY, 12 APRIL 2018: RAF CENTENARY: SOUTHERN AFRICAN AIRMEN OF THE GREAT WAR, 1914-1918 by Mr Michael Schoeman (and assisted by CDR Mac Bisset).

To mark the centenary of the establishment of the RAF on 1 April 1918, military aviation historian and author, Michael Schoeman, will give a talk on the 3,000 South African airmen who served in the First World War, 1914-1918.

Our speaker will pay homage to, and tell the story of the first aspiring aviators sent to England to be trained as military pilots. This took place in 1914, when the fledgling Union of South Africa was barely four years old. Although not the first South Africans to receive flying training in England, these aspiring military pilots were the core of what was to become the South African Aviation Corps. Although the South African part in the formation of the Royal Flying Corps were by all standards very small, they played an important role in the formation, growth and success of British Military Aviation. The RFC went to war with less than 200 aircraft and about 2,000 officers and other ranks. It ended the conflict as a mighty organization with more than 22,600 aircraft and over 291,000 personnel.

The above is also a summary of Mr Schoeman's recently-published book on the topic, titled The Register of Southern African Airmen of the Great War, 1914-1918, in cooperation with CDR Mac Bisset (SAN, Retd.). Mr Schoeman is the author of the highly-acclaimed series of books, Springbok Fighter Victory: SAAF Fighter Operations, 1939-1945 (Vols. 1-6). Copies of his latest book will be on sale at the meeting at R400,00 a copy.

The lecture will be illustrated.

THURSDAY, 10 MAY 2018: DETAILS OF THE TOPIC AND SPEAKER WILL BE ANNOUNCED CLOSER TO THE ACTUAL DATE.

BOB BUSER: Treasurer/Asst. Scribe

Phone: 021-689-1639 (Home)

Email: bobbuser@webafrica.org.za

RAY HATTINGH: Secretary

Phone: 021-592-1279 (Office)

Email: ray@saarp.net