Newsletter/Nuusbrief 148

January/Januarie 2017 The December meeting took place on Monday 12th at the usual ECVCC venue. It began with a minute’s silence in honour of fellow SAMHS member Ken Gillings, who died tragically on 9th December. Members were then given the opportunity to share their memories of Ken.

The members’ slot was utilised by Franco Cilliers to briefly outline the nature of Long Range Rifle Shooting. This is defined as shooting at targets that are further than 1.1km from the shooter. The rifles used, such as the well-known Barrett range, are specially designed for the task. They are commonly chambered in 12.7 x 99mm, better known as 50cal.

There are several factors that come into play when shooting at a long range. These are

The curtain raiser by Malcolm Kinghorn focused on Lieutenant General Leonard Beyers, who is on the SA Legion’s list of military graves to be visited on their annual Poppy Run in November.

The more familiar General Beyers is Christiaan Frederik Beyers (1869-1914) who, at the start of the Anglo-Boer War in 1899, enlisted as a burgher and was quickly promoted to General. In May 1902, he was elected chairman of the Boer delegates discussing peace terms at Vereeniging. In 1905 he was elected to the head committee of the Het Volk party of Botha and Smuts although his bittereinder views were at odds with the reconciliation policy promoted by them. When the Transvaal was granted responsible government in 1907, Beyers was elected Speaker of the Transvaal Legislative Assembly. After Union in 1910, he became a Member of Parliament. When the Union Defence Force (UDF) was established on 1st July 1912,Brigadier General Christiaan Beyers was appointed Commandant General of the Citizen Force and Brigadier General Lukin Inspector General of the Permanent Force.

When war was declared in 1914 and a South African expeditionary force was mobilised for the invasion of German South West Africa, Beyers resigned his post as Commandant General. In a letter addressed to General Smuts, then Minister of Defence, he stated his disapproval of the Government's intention to invade German South West Africa and claimed that this disapproval was shared by the great majority of the Dutch-speaking people of the Union. Beyers was in the car with de la Rey when the latter was accidentally shot dead by police at a roadblock near Johannesburg while searching for the Foster criminal gang. Beyers had been meeting with de la Rey, de Wet and others to discuss an armed anti-war rebellion. He was to coordinate the uprising in the Transvaal, and de Wet in the Free State, but drowned crossing the Vaal Riveron 8th December 1914, while trying to evade government forces.

Lieutenant General Leonard Beyers (1894-1959), was born in Kimberley and attended Pretoria Boys High School. He served in both World Wars, but not in operations and so chose not to wear the medals he was awarded. His military career began when he was commissioned in the Witwatersrand Rifles in February 1913. He was attached for training to the Royal Scots Fusiliers, then in South Africa. He later transferred to the Pretoria Regiment and in 1914 enlisted in the Permanent Force. In 1926 he attended the British Army Staff Course at Camberley, after which he became an instructor at the South African Military College. In 1931 he was Officer Commanding, 5 Military District, which is the Pretoria region. In 1932 he became Director of Prisons.

In 1937 he returned to the UDF to become Deputy Chief Commandant of Burger Commandos and then, as a Brigadier General in September 1940, Director General Defence Rifle Associations, which from 1913 to 1949 was the name of what we knew as the commandos. He was promoted to Major General and appointed Adjutant General in 1942. He acted as Chief of the General Staff several times during the Second World War and was promoted to Lieutenant General and appointed Chief of the General Staff in 1949. Beyers resigned in 1950 in protest against interference in the running of the UDF by the then Minister of Defence, Erasmus.

He wrote to the Prime Minister as follows: My resignation (is) in protest against the unconstitutional and unwarranted interference in the functions of the Chief of General Staff who, in fact and in law, is the Commander-in-Chief of the Forces in South Africa. The facts are that the Minister sought to change the strategic dispositions of units and to appoint, promote and transfer both officers and other ranks, without sufficient knowledge of their qualifications and without reference to the General Staff, of which I was the head. Without reference to me, he created posts for the absorption of persons in whom, irrespective of their unsuitability or otherwise, he personally reposed political confidence. Political ambitions should not be allowed to intrude into the responsibility of command and functions of military organisations.

The UDF had two General Beyers. Both resigned senior appointments on political grounds, one on either side of the political divide of their time. Christiaan Beyers is the better known, while Leonard Beyers has faded into obscurity.

The main lecture, titled The Sky Generals: three South African airborne visionaries was delivered by Mac Alexander.

Vertical envelopment is a form of military manoeuvre that entails the outflanking of the enemy from above, rather than from one side or the other. It is normally accomplished by means of parachuting or assault landing. The latter can be done by fixed wing aircraft on a suitable airfield, or by helicopter. Such actions are termed airborne operations.

During research into the concept of airborne operations in the South African military, it became apparent that three figures played an important part in its development: General Sir Pierre van Ryneveld, KBE,CB,DSO,MC, who was Chief of the General Staff of the Union Defence Force (UDF) from 1933 to 1949; Commandant-General Stephen Melville, SSA,OBE, who was head of the South African Defence Force (SADF) from 1958 to 1960; General ConstandViljoen, SSA,SOE, SD,SM, who was Chief of the SADF from 1980 to 1984. They did so over a period of some 45 years; all three rose to the highest position in their profession and each made an unintentional sequential contribution to the thinking about and implementation of an airborne capability.

Pierre Van Ryneveld, was born in Senekal in 1891 and educated at Grey College, Bloemfontein, the University of the Cape of Good Hope and Imperial College in London, where he obtained a BSc in Engineering. At the outbreak of the First World War, he joined the Royal North Lancashire Regiment, serving with them in France and in 1915 transferred to the Royal Flying Corps, where he trained as a pilot. He saw action in the Middle East and on the Western Front and by the war’s end had risen to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel and was the Commanding Officer of the 11th Army Wing.

After the war and the death of Louis Botha, Jan Smuts, the new Prime Minister, wanted to establish the South African Air Force. He felt that Van Ryneveld, then in the newly established Royal Air Force, was the right man to do this, and recalled him to South Africa. Now 29 years old, he joined Major Quinton Brand in 1920 in the first attempt to fly from England to Cape Town. Despite two crashes, they reached Cape Town in a DH9 named Voortrekker (their third aircraft), divided a prize of £5000 awarded by the South African government and were both knighted. This feat placed Van Ryneveld firmly in the limelight as an exceptional airman. He was appointed to full Colonel in the Permanent Force, made the Director of Air Services, andwas charged with establishing the South African Air Force (SAAF). In 1921 he led a bombing mission against the Bondelswartuprising*, and in 1928 established an air record of six hours and 55 minutes for the first non-stop flight between Cape Town and Pretoria. In 1929 he was appointed Commandant of the South African Military College, still retaining his position as Director of Air Services (effectively, the head of the SAAF) until 1937.

By then a Major General, Van Ryneveld was appointed as Chief of the General Staff in 1933 and promoted to Lieutenant General. He held this appointment until his retirement in 1949, having been promoted to full General in 1945 as a reward for his wartime services. During the war, he saw the UDF grow from a strength of 3000 officers and men to a strength exceeding 200 000.

In 1926 Van Ryneveld himself carried out the first intentional parachute jump known to have been made by a South African serviceman. This jump convinced him of the value of the parachute and 25 were purchased by the SAAF from the RAF. It appears that the parachutes were first tested in South Africa with dummy weights attached below an Airco DH-9 biplane at Zwarkop Air Station in Pretoria in April 1927. Van Ryneveld then approached his handful of young, recently qualified Permanent Force pilots and asked for volunteers to test the parachutes. He had decided that six trial descents would be made and that he would himself make the first one. The Officer Commanding Zwartkop Air Station, found himself number two in line, followed by another First World War veteran pilot and three nervous young Second Lieutenants.

Twelve years later, South Africa became the first of the Dominions to declare war on Germany with Van Ryneveld as the Chief of the General Staff. One of the first actions of the Union government was to commandeer the eight Junkers Ju52/3 aircraft, which were in service with the South African Airways and transfer them to the SAAF. In mid-1940, they were used to train two battalions of troops for a tactical assault landing operation At the time, neither Britain nor any of the Dominions had aircraft with this capability and there existed no airborne doctrine or thinking in any Allied armed forces. Yet the Germans had just astounded the world by their spectacular and highly successful use of airborne troops in the conquest of Belgium, the Netherlands and Crete. Only in South Africa was the concept immediately grasped and applied to a strategic plan.

After the successes of the Germans,the Allies began building up an airborne capability of their own. Sir Pierre van Ryneveld immediately set investigations rolling to establish an airborne brigade of both parachute and glider troops. This did not however prove to be a practical possibility and the idea was reduced to a company size of UDF personnel to be employed as part of a British parachute battalion

For four months, these approximately sixty volunteers were given intensive training in ‘commando tactics’, after which they were to have gone to the Middle East for their parachute training. Faced however with an acute problem of finding sufficient manpower for the 6th SA Armoured Division, which had been committed by the UDF to the Italian campaign, Van Ryneveld was compelled to withdraw the SAAF Paratroop Company from the project. It was the end of South Africa’s efforts to field its own airborne capability during the Second World War. Sir Pierre van Ryneveld should nonetheless be acknowledged for his visionary approach to airborne operations at a time when the concept was in its infancy.

Born in Matatiele, Natal, in 1904, Stephen Melville was, like Van Ryneveld, educated at Grey College, Bloemfontein. After matriculating, he worked briefly in a Cape Town bank. He had an adventurous spirit, however, and soon left to join the merchant marine as a stoker on steamers. After two years at sea, travelling the world, he returned to South Africa in 1924, and as a 20-year old, joined the SA Mounted Rifles as a trooper later transferring to the artillery. An accomplished boxer, he became the South African amateur light middleweight champion. Some sources indicate that he then left the Defence Force to become a professional boxer, spending time in the USA.

He then appears to have re-joined the UDF and in 1929 he trained as a pilot and transferred to the SAAF. In January, 1940, after the outbreak of war, he led the first squadron to be deployed outside of the Union for operations in Abyssinia. By 1942 he was a Colonel, and commanded the air wing consisting of one SAAF squadron, two squadrons of the Royal Navy’s Fleet Air Arm and an RAF flight during the Madagascar campaign. He was aboard HMS Ramillies when the Japanese torpedoed her in Diego Suarez harbour. He survived to serve in East Africa and Italy, was awarded the Order of the British Empire for his services and was mentioned in dispatches.

After the war he remained in the SAAF, was promoted to Brigadier and then Major General, in which rank he served on the General Staff, initially as Air Chief of Staff from 1954 to 1956 (effectively heading the Air Force), then as Inspector General of the UDF from 1956 to 1958, and finally, he was appointed as Commandant General of the SADF in 1958. Melville was the brother-in-law of J.G. Strijdom, who succeeded Dr D.F. Malan as Prime Minister in 1958. He retired at the end of 1960.

In May 1957, while Inspector General, Major General Melville, during a special conference of the General Staff Committee, raised the point of there being a need to create “a hard-hitting and highly mobile force, possibly also air-transportable.”

At the time, in the wake of the Second World War, there were numerous conflicts raging around the world, and their nature was emphatically insurgency-based rather than conventional. The General Staff of the UDF was undergoing a process of re-alignment of thinking to make provision for this change. This was particularly so, given the internal rumblings for political change in South Africa. The emphasis in training in the UDF began to shift to ‘Internal Security Operations’ (known as Binnelandse Beveiliging in Afrikaans). To this end a decision was made in 1957, following up on Melville’s suggestion, that a Permanent Force mobile unit should be established. This would provide an immediately available force deployable in the event of unrest or disturbances taking place anywhere in the country. Until then, there was no standing Army combat unit available in South Africa and the part-time, largely volunteer Citizen Force would need to be called up and mobilised should there be a requirement for troops. In the past this had proved to be time-consuming for the military and disruptive for the civilian sector.

The new unit, known as the Mobile Watch, were Army units consisting only of Permanent Force troops. Although they wore the cap badge of the South African Engineer Corps, this did not reflect their primary role. They were intended to be internal security units with an air-transportable capability, to be ready to deploy to any part of South Africa at the greatest possible speed. This essentially required them to be an infantry force, although they were also trained to operate armoured cars. The main intention with the Mobile Watches was to have a light force that could be rapidly transported by air, while the Active Citizen Force and Commandos were being mobilised. However, they were trained in military engineering tasks so that when not deployed, they could be used for ‘Land Service’ (Landsdiens), or service to the country. This was defined as non-military assistance to other government departments, including the building of dams, repair of flood-damaged bridges, aid in drought-stricken areas and the provision of trained recruits for other departments.

The outbreak of violent unrest in the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland in 1959 brought home the need for a true vertical envelopment capability. Sabotaged bridges and culverts, road blocks and airfields littered with petrol drums, rocks and tree stumps had cut off isolated government outposts, while the rainy season had further delayed soldiers making use of wheeled transport from moving around. By then, Melville was Commandant General of the SADF. He now overrode the Air Force’s initial reluctance to modernise and expand itstiny and obsolete helicopter capability. A study group of senior Army, Air Force and Police officers was sent to Algeria to examine the French employment of helicopters in the insurgent war then in progress.

The departure of the political ideologue, Erasmus, as Minister of Defence during 1959, to be replaced by J.J. ‘Jim’ Fouché, immediately saw a more pragmatic and less ideological direction being given to the SADF. In addition, the Sharpeville incident of 21st March 1960 lent further impetus to airborne thinking as South Africa faced increasing hostility from the international community. Soon after this, in July 1960, Melville issued an urgent instruction to the Army Chief of Staff, to investigate the training of a Mobile Watch in parachuting techniques. A formal appreciation was done by Commandant Jan Burger, a decorated Second World War veteran and artillery officer who had been trained by the Americans in both parachuting and glider operations in 1949, assisted by Major ‘Pik’ van Noorden, a Second World War paratrooper who had been seconded to the Royal Marines. At the same time, Melville had been pressurising the Air Force on the acquisition of a fleet of modern helicopters. By July, a decision was taken to purchase six French Alouette II helicopters for training, followed by 24 Alouette IIIs. The following month a plan of action was set out for the selection and training of a nucleus of volunteers as paratroopers and parachute instructors in the United Kingdom.

Melville’s promotion of an airborne capability may well have been a consequence of his somewhat chequered and unconventional background. He had a broad exposure to a range of military challenges, which would doubtless have made him a more lateral thinker than those general officers with a narrow, traditional military career. As an airman who began his military career in the Army, his thinking was probably uniquely ‘joint’.It was unusual for someone who had not spent his whole life in the military to rise to the top position in the Defence Force.

While he has been criticised as not having been an effective defence chief and his retirement was brought forward because of this, the role of Stephen Melville in airborne thinking cannot be denied. First, as Inspector General of the Defence Force, he initiated airborne thinking on the General Staff; and later, as Commandant General, he appears to have been the driving force behind the establishment of South Africa’s first parachute unit and in acquiring a helicopter fleet. This indicates that he could conceivably be seen as the father of South Africa’s airborne forces, despite the fact that he left office three months before the formal establishment of 1 Parachute Battalion on 1st April 1961.

Yet another country boy, Constand Viljoen, was born in Standerton in 1933, one of twin boys. He and his brother volunteered for a year’s training in the Military Gymnasium in 1952, at the end of which Constand joined the Permanent Force. He attended the Military Academy, then a branch of the Military College, in Voortrekkerhoogte, and graduated with a BSc (Mil) from the University of Pretoria in 1955. Viljoen was posted to the artillery and served as a junior officer in 4 Field Regiment in Potchefstroom. From 1957 to 1958 he was aide de camp to the Governor General of the Union. Subsequently a gunnery instructor at the School of Artillery and Armour in Potchefstroom, he was promoted to Major in 1963 and appointed a battery commander in 4 Field Regiment. Three years later he was promoted to Commandant and appointed Officer Commanding the now separate School of Artillery. Promotion to Colonel quickly followed, and he was sent as the second-in-command of OFS Command in 1967. While there, he completed the parachute course at 1 Parachute Battalion, the most senior rank to do so.

The following year he was appointed Officer Commanding what was now the SA Army College. He was sent there with the specific task of revamping senior command and staff duties training in the Army, and instituted a mobile warfare approach and doctrine, in stark contrast to the previous positional approach to operations. The following year he was appointed Director of Artillery at Army HQ. Thereafter he was promoted to brigadier and appointed the Director of the Defence Force’s Management Services, responsible for organisational changes.

By 1974 he was the Army’s Director of Operations. In 1975, as a Major General, he became the Director of Operations for the entire Defence Force. He was appointed General Officer Commanding 101 Task Force for the final phase of Operation Savannah in 1976. Later that year he was promoted to Lieutenant General and appointed Chief of the SA Army. He held this position until his promotion to full General in 1980, when he became Chief of the SADF. He retired in October 1984.

It is an indication of Viljoen’s interest in vertical envelopment that he volunteered for parachute training as an artilleryman and a full colonel. At the time, the SADF had no airborne artillery and the highest rank in the parachute battalion was commandant (lieutenant colonel). Viljoen, therefore, had nothing to gain from undergoing the tough selection and demanding training, other than a better grasp of what it entailed to be a paratrooper and what the potential was of vertical envelopment as a form of manoeuvre.

WhenCommandant General Hiemstra retired on 31st March 1972, Viljoen almost immediately drew up a memorandum on the operational need for such a Special Forces unit to be formally recognised and established. He was an ardent proponent of the manoeuvrist approach in the war that he realised lay ahead. He now pointed out that the new doctrine he had been instrumental in drawing up while at the Army College required utilising the spatial vastness of southern Africa to compel any opponent to fight on extended lines of communication, exposing these and making them vulnerable to attack. It also necessitated the acquisition of tactical intelligence, often hundreds of kilometres behind enemy lines. To meet this requirement, a specialist unit of highly trained soldiers was required. He recommended that the Operational Test Group be used as this unit and that it be given the name ‘1 Reconnaissance Commando’. The new Commandant General, Admiral Hugo Bierman, and the Defence Minister, P W Botha, supported Viljoen unconditionally and South Africa’s first Special Forces unit was accordingly made official.

Viljoen showed the same propensity to integrate the airborne concept into mobile warfare doctrine as he did the Special Forces concept. In June 1974, when the situation in Angola was bordering on complete chaos due to the revolution in Portugal, he was the Army’s Director of Operations. Intelligence reports indicated that a group of possibly 200 SWAPO insurgents was moving from Zambia through south-east Angola in the direction of Bwabwata on the border with the Caprivi Strip. The SADF had only a company of infantry deployed in the entire Western Caprivi and the element at Bwabwata was only an under-strength platoon.

Brigadier Viljoen saw this as an ideal opportunity for a parachute operation which he put into effect at short notice. It was the first operational parachute deployment by South Africa. The paratroopers immediately moved out to the north, into Angola, and set up ambushes along the routes that had been appreciated as likely ones the insurgents would take. The following day a second company was dropped as a show of force to the local population at Kongola, inside the Caprivi. They would be on standby to back up the first company which linked up with two teams of Special Forces already in the area, and began to search for the insurgents, who appeared to have dispersed after learning of the arrival of the paratroopers. After more than two weeks of hunting through the bush, the Special Forces and paratroopers finally caught up and made a successful contact with the insurgents. Many lessons were learnt from this operation and after that Viljoen instructed that a Paradak (a Dakota equipped for dropping paratroopers) and a platoon of paratroopers be permanently stationed at Rundu on a rotational basis. He also insisted that a suitable Dropping Zone be identified at every base in the Caprivi so that reinforcements could be dropped if necessary.

Viljoen’s next contribution to the airborne concept in the SADF came when, as a Major General, he was General Officer Commanding 101 Task Force during the latter part of Operation Savannah and afterwards. He established the Fire Force at Ondangwa in Owambland with a company of paratroopers, two Puma helicopters, an armed Alouette command helicopter and two Alouette gunships. He employed the capability extremely aggressively, ensuring that the Fire Force was almost constantly employed. The paratroopers had to give him a daily debriefing on their actions, with suggestions for changes in organisation, tactics and armament. As a result, the conventional infantry organisation of a company was tailored by the paratroopers to fit the available aircraft.

When he became Chief of the Army, Viljoen (by then a Lieutenant General) arranged for officers from 1 Parachute Battalion to be attached to Rhodesian Fire Forces to gain experience in the technique. Later, the South African paratroopers deployed two Fire Forces in Rhodesia in 1979 and 1980. Viljoen argued for, and obtained, authority to deploy them deeper than was initially approved and personally visited them during the Rhodesian deployment.

In 1978 Viljoen initiated the establishment of a parachute brigade. He had always propagated a larger, balanced airborne force, with greater flexibility than a purely infantry unit. He was also responsible for propagating and gaining approval for the parachute assault on Cassinga in that same year. This was the largest airborne assault carried out by the SADF, and Viljoen’s interest in an action of this kind is illustrated by his insistence on being flown to the battlefield while the operation was still in progress. He had based much of his belief in the success of the operation on a similar Rhodesian operation that had been carried out six months earlier.

Although Viljoen made mistakes that almost torpedoed his dream of a parachute brigade, it did eventually take shape, and he must be given credit for the vision and drive that brought it into being. His firm belief in and understanding of vertical envelopment resulted in the creation of the most potent airborne capability that has ever existed in an African country.

In conclusion, these were the three generals in the South African saga of going by air to battle. Van Ryneveld grasped the value of an airborne capability when the concept was still in its infancy, but was unable to implement it because of other Second World War priorities. Melville saw its value in the Cold War conflicts and set the ball rolling to put the capability in place. Viljoen was the practical implementer who understood the idea and brought it to fruition.

* An interesting article relating to Sir Pierre van Ryneveld and his mode of operation, ‘Operation Ipumbu’ by Brigadier J B Kriegler, can be found in the [SA] Military History Journal 2 (4) 128-131. It is online at http://samilitaryhistory.org/vol024jk.html[Eds.]

Future meetings and field trips/ Toekomstige byeenkoms en uitstappe

The next SAMHSEC meeting will be on Monday 9th January 2016 at 19h30 at the Eastern Cape Veteran Car Club in Conyngham Road, Port Elizabeth. The member’s slot will be by Ian Pringle on The Diary of Mr I Staples – a Burgher who fought in the War of 1851-1853. The curtain raiser will be by Michael Newcombe on The Battle of Mogadishu and the main lecture will be The Bayeux Tapestry – the Norman Invasion of England by Ian Copley

Matters of general interest / Sake van algemenebelang

Obituary / Lewensberig

Members of the South African Military Societyare deeply saddened by the tragic and untimely death of Ken Gillings. A former RSM of the Natal Field Artillery, Ken was a giant among South African military historians. Not only did he know most of South Africa’s battlefields, and by extension the circumstances which brought them about, like the back of his hand, but he also recorded a good deal of his vast knowledge in print, on Facebook, and blogs such as his Bush and Battlefield Tours. He loved the bush too and often integrated his battlefield tours with wild places and wildlife. While his interests focused to some extent on the Anglo-Zulu War and the Anglo-Boer War, he also had wide ranging knowledge on other aspects of military history, such as artillery, as any perusal of the Military History Journal over the past 30 years will show. He authored or co-authored a number of books, including the highly acclaimed The Road to Ulundi Revisited published earlier this year.

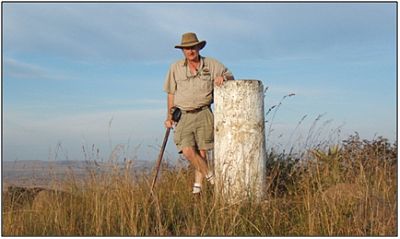

Ken sharing his knowledge and wisdom in characteristic pose,

on this occasion on the summit of the Shiyane / Oskarsberg at Rorke's Drift.

Ken will long be remembered with affection and respect by people all over the world who had the good fortune of knowing him or accompanying him on field trips.He was a kind and generous person readily sharing whatever knowledge and insights he had. His personal impact and his large volume of writing will also be felt by, and influence, future generations. SAMHSEC’s sincerest condolences go to his family: their loss cannot be imagined. RIP Ken.

World War I Centenary Years / Eerste Wêreldoorlog Eeufeesjare

Major engagements in January 1917

The battle of Khadairi Bend was one of a series of diversionary attacks over the course of January aimed at undermining Turkish defences and maintaining the initiative during the Second Battle of Kut (see SAMHSEC Newsletter 147). Khadairi Bend was a strongly fortified position, but nevertheless, and despite impressive Turkish opposition, fell to the Allied forces on 29th January.

Websites of interest/Webwerwe van belang

Historic aircraft

The fastest aircraft of WWII and the Luftwaffe’s worst nightmare.

Nikola Budanovic War History Online 3rd December 2016

[The site includes a sort film clip of the raid on Amiens prison.]

The flying anti-aircraft battery: The Bell YFM-1 Airacuda

Vintage News 3rd November 2016

The Tank Museum monopoly released – buying and selling tanks instead of properties

The Tank Museum 22nd October 2016

Ancient history

Circumvallation: How the Romans mastered surrounding towns to conquer populations

Andrew Knighton War History Online 18th November 2016

World War I

World War I Soldiers’ wills digitised for the Web, giving an intimate insight into soldiers’ lives

George Winston War History Online 7th November 2016

Milunka Savić: Possibly the most decorated female in the history of warfare

Holly Godbey War History Online 3rd December 2016

The glider operation to take Pegasus Bridge

Jinny McCormick War History Online 4th November 2016

Andrew Knighton War History Online 4th November 2016

Secret German World War II Base rediscovered near North Pole

Tom Metcalfe Live Science 5th November 2016

Weaponry

Light machine guns during WWII and beyond – the British Bren Gun vs the German MG 34 Spandau

Joris Nieuwint War History Online 23rd October 2016

Resource materials of military historicalinterest/

Bronmaterieel van krygsgeskiedkundigebelang

The medal detective BBC News Magazine 21st December 2016

Members are invited to send in to the scribes, short reviews of, or comments on, books, DVDs or any other interesting resources they have come across, as well as news on individual member’s activities. In this Newsletter, there have been contributions by Malcolm Kinghorn, Barry Irwin and Michael Irwin.

Chairman: Malcolm Kinghorn: culturev@lantic.net

Secretary: Franco Cilliers: Cilliers.franco@gmail.com

Scribes (Newsletter): Anne and Pat Irwin: p.irwin@ru.ac.za

Society’s Website: http://samilitaryhistory.org

TAILPIECE:

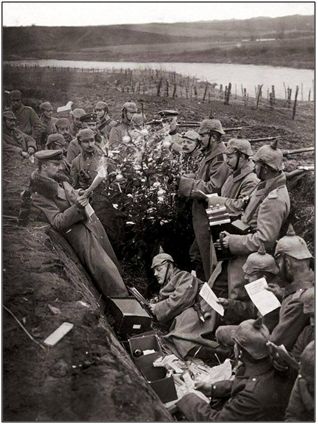

Christmas in the German trenches, First World War.