Newsletter No. 488

October 2016

Our first speaker at the September 2016 meeting was Brian Conyngham, who is a specialist in medals and similar commemorative items of militaria. His topic was "South African Memorial Devices issued to next-of-kin” and covered the period from the World War 1 through to the South African Border War. In order to keep the images in the correct sequence, they are reproduced below as per Brian's talk.

World War 1 Memorial Plaque

During WW 1 a competition was held in the United Kingdom to produce a suitable memorial to be presented to the next-of-kin of servicemen and women who had died on active service. The results of the competition were officially announced on the 20 March 1918 in a Wednesday edition of The Times newspaper. Edward Carter Preston of the Sandon Studios Society was the winner.

Edward Carter Preston’s winning design comprises the figure of Britannia, classically robed and helmeted, standing facing to her left, holding a laurel wreath crown in her extended left hand. Using her right hand she is supporting a trident against her body. In the foreground stands a mature male lion. Above Britannia’s left arm and alongside her right arm are small dolphins representing Britain's sea power. Below the main lion is an area known as the exergue and in this space is a smaller lion engaged in a symbolic confrontation showing the smaller lion pouncing on an eagle, a direct reference to the Allied victory over the Central Powers. There were two versions produced He Died For Freedom and Honour and She Died For Freedom and Honour. Each had the persons full names cast onto the Memorial Plaque.

World War One Memorial Scroll

Along with the Bronze Memorial Plaque there was also an issue of a Memorial Scroll, each one individually inscribed with the name and regiment of the fallen men and women.

All service personal regardless of gender, race, colour and creed were eligible to receive an issue. The figures taken from the Official Roll of Honour in the House of Assembly gives the total figure for South Africans who died in WW 1 as 13,179, this figures can be safely used to determine the number of Memorial Plaques and Scrolls produced for South African next-of-kin.

World War Two South African Plaque of Remembrance

The Plaque of Remembrance was designed by Mr Charles Evenden for the SA Government and produced at the SA Mint (SAM) outside Pretoria after the war. There were two versions: Standard Version, total issued 10,897 and a Jewish version, total issued 250. There are five variations of naming scrolls: Killed in Action, Died of Wounds, Died on Service, Native Military Corps and Merchant Navy.

World War Two South African Brooch of Remembrance

Two different Replica Brooch issues were also issued along with the plaques to the Next-of-Kin which were copies of the main emblems on the two plaques issued.

South African Defence Force issues for losses on the South West African border and Operation Savannah, 1974 to 1976

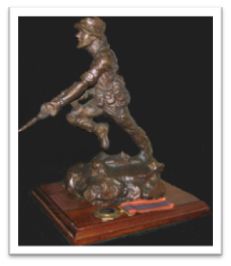

South African Defence Force Memorial Statuette “The South African Soldier” 1974 to 1976 was commissioned by the SADF in the mid 1970’s.

The original design was created by artist Cpl Henk van der Merwe during his initial National Service. During his National Service he served as an Infantry instructor in the SADF. Height of casting without base: 19 cm and weight: about 1,7 kg. At a parade held on the 9th October 1976 at the Army College in Pretoria, 48 “South African Soldier” Statuettes were issued to the next-of-kin of fallen South African soldiers.

South African Defence Force Memorial Plaque issues for losses 1977 to 1997 and possibly later?

The earliest known mention of a Memorial Plaque to be issued to the next-of-kin of fallen SADF soldiers has been found in a letter dated 2 February 1987. Unlike in WW 2 no separate Jewish version of these SADF memorial plaques was produced. The SADF Memorial Plaque was issued to all service personal irrespective of how they had passed away whilst in the service of the SADF.

It appears they were backdated to 1962 and issues made to the Next-of-Kin, according to documentation found. Therefore it can be considered an accurate indication of actual SADF Memorial Plaque issues up to 1997 were 2,154.

The Main talk was given by immediate past Chairman Charles Whiteing and was entitled “D-Day 1066; Two Anglo-Norman Epics”. By means of a power point presentation, Charles skilfully compared the events of 1066 and 1944.

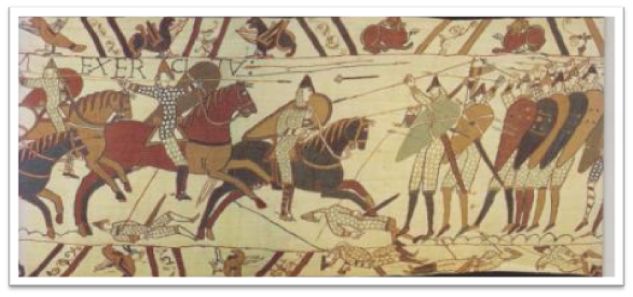

His was a story of two battles, 878 years apart, of two amphibious landings and two tapestries. These are the Bayeux Tapestry and the Normandy Embroidery which illustrate the respective the 1066 and 1944 channel crossings.

The Bayeux Tapestry has become the definitive image of the Norman conquest of 11th century England, as with the Overlord Embroidery in Portsmouth depicting the D Day landings. The weavers of the Bayeux Tapestry depicted events leading up to the battle and subsequently picked out key episodes of the battle, and as such the actual sequence of events had to be guesswork. It represents the Norman point of view as there's no English equivalent. The tapestry is on display in the Museum of Queen Matilda in Bayeux, France. William's half brother Odo who was the Bishop of Bayeux ordered it to be made to commemorate William's victory. The tapestry is 50cm (20”) wide and 70m (250 ft) long, claiming to be the longest piece of embroidery in the world. It's embroidered on linen with coloured woollen yarns, depicting 50 battle scenes.

As it's a woven piece of work it's technically not a tapestry but an embroidery, but has always been referred to as such.

During the Second World War, it was stored in an air raid shelter in Bayeux, a city closely associated with another battle in 1944.

On the 28 September 1066, William Duke of Normandy invaded England with an army of 7,000 men to lay claim to the throne of King Harold 2nd. Which he intended to conquer to lay claim to the throne of England which he felt was his birthright.

Following the death of Edward the Confessor on 5 January 1066, William protested his right to the throne to the English court following King Harold’s coup d-état. However his protests were in vain and this was his motivation to invade England and lay claim to the kingdom he felt was his right by birth.

The intended seaborne invasion required sound preparations which included the building of special ships, and gathering thousands of strong horses needed to withstand the long and potentially rough sea passage across the Channel.

The vassal lords and knights in Normandy were approached to assist with the enlisting of troops of the right calibre. To strengthen his case, William also appealed to the courts in Europe including Pope Alexander 2nd who in turn gave his papal blessing and authorisation to reform the English Church. William's plans did not include having to contend with defensive beach obstacles, well sited coastal defences, land mines, machine guns, mortars, and an enemy who had been at war for four years. He did not require an air force to defend his operation, nor anti aircraft weapons for attacks by enemy aircraft.

Following a preparation period of about seven months, William of Normandy set sail with his invasion fleet of about 600 transports from the mouth of the River Somme. His fleet had to accommodate some 7,000 men including 2 to 3,000 knights, squires, horses, arms and supplies. Williams’s flagship was named the Mora which had been presented to him by his wife Matilda. However bad weather frustrated his initial attempts to set sail, and two weeks were to pass before the prevailing winds were suitable.

Another invasion 878 years later also experienced bad weather, but a 24 hour window of opportunity presented itself. Its commander gave the order "Let's go", and the biggest invasion force in history sailed for France.

The comparative logistics of the 1944 invasion are staggering. They included 6,939 vessels of all types, 1,100 transport aircraft deploying 17,000 airborne troops, and finally culminating with 159,000 troops streaming ashore on the five designated beaches on the coast of Normandy, France.

One of William's qualities was his skill in managing men which comprised not only Normans, but volunteers from Picardy, Brittany, Ile de France, Flanders and Aquitaine. A greater motivation for his men was the potential rich rewards to be gained by invading this kingdom of unknown but reputably immense wealth.

His ships beached in Pevensey Bay in Sussex where his first task was to order the construction of a castle within the ruins of an old Roman fort.

The following day William left a garrison in the fort and proceeded inland with his forces to Hastings.

Here he raised a Motte-and-Bailey castle not far from the shore line. On 1 October the news of the invasion reached King Harold of England at York where he had been attending celebrations following his victory over the Vikings at Stamford Bridge. Proceeding south via London, Harold recruited an army of between 6 to 7000 men and on the afternoon of 13 October he reached Senlac Ridge on Battle Hill near Hastings.

The area had been foreseen as a potential battleground for the long expected Norman invasion. Senlac was a gently sloping ridge with a marsh area to the south around Asten brook with the western and eastern flanks protected by deep ravines and thick brushwood.

An even steeper ridge protected the northern side which would have prevented the Normans attacking Harold’s army from the rear. News of Harold’s arrival reached William and at dawn he left his base under the cover of darkness.

As the sun rose on Saturday morning, the forward Norman scouts could see the English on the ridge about two miles away.

William troops advanced and about 08h00 reached Hedgeland–on-Telham on the south east side of what later became the town of Battle. Ahead of him the ground sloped downwards to the southern side of the marshy valley below. His men stopped about 400 yards from the English front ranks and he arranged his forces in three attack lines.

First in line were his archers with a few crossbowmen among them, followed by his heavy infantry with many wearing coats of mail, and behind them were the cavalry.

He then divided these lines into three blocks or lateral divisions. On the west were the Breton volunteers, in the centre the Normans led by William, and on the east, his Franco-Flemish troops. At 0900 on 14 October, trumpet blasts heralded the beginning of the battle. The Bretons were the first to reach the Harold’s lines, but by 10h30 were forced to retreat as they were unable to sustain a break through. The Saxon infantry then broke the ranks of their shield wall on the left flank to pursue the Bretons.

William responded by sending his armoured knights forward who intercepted and succeeded in cutting down large numbers of Saxon infantry. But in certain sectors they had to retreat and regroup. At 11h00 William personally led a third attack, but progress was slow as the ground was slippery and littered with dead men and horses from the previous attack.

For two hours, waves of attacks against the English wall of shields followed, but the Normans were constantly repelled. At 14h00 William recalled his men to their own lines beneath the ridge to regroup, rest, and eat.

Harold used this respite to reinforce his thinning line as unbeknown to the Normans, Saxon losses had been considerable, and he was concerned he would have insufficient men to fill the increasing gaps in his defensive lines. His men were however better rested than the Normans who had to face the debris ridden slope as they prepared for a renewed attack.

William had lost 1800 to 1900 men in around five hours of continuous fighting. This represented a quarter of his army, together with the loss of many horses that had been cut down by the axe-wielding Saxons Huscarls.

These Huscarls were a bodyguard of the Anglo-Dutch Aristocracy who had ruled England prior to 1066. They represented an elite bodyguard of crack troops who were among the best troops in Europe and were armed with the dreaded two handled axe.

In one illustration, a Huscarl wields his long handled axe which could decapitate a horse. He has a kite shaped shield on his back which enables him to have a two handed grip on his axe to inflict extra strength.

Many of William's men were now fighting on foot and were at a distinctive disadvantage, as the cavalry charge of the Middle Ages was a fearsome military tactic used in battle.

In the marshy area the Bretons had been stunned by the English assault and a rumour spread through the ranks that William had been killed.

Hearing this, Duke William was seriously alarmed, and proceeded to ride among his soldiers raising his helmet visor to reassure his men as depicted in the Bayeux Tapestry. Ahead of him a mounted knight carries the Papal Banner. William then decided that his entire army would attack as a single formation with all arms combined and he personally led this vigorous counter attack.

The Normans were concerned with injuries sustained by their horses during the hand to hand fighting. Improvement in saddles, spurs and stirrups had enabled the Norman knights to ride into battle, compared to the English knights who usually dismounted to fight on foot. The shields were of two designs, rounded for the infantry, and elongated for the mounted troops. In addition to the leather thongs that fastened the shield to their arm, the horsemen had a strap around their shoulders. Personal insignia were emblazoned on the shields which included illustrations of mythical beasts. The knights wore heavy chain mail but many of the peasant soldiers wore simple tunics. In the heat of battle, a sword could split a man's skull, and the two handled axe having the ability to decapitate a man`s head.

The last phase of the battle commenced at about 15h00 and took place further up the ridge which was preceded by devastating volleys of arrows by waves of Norman archers.

As they were firing up the slope, the archers fired their devastating volley of arrows high into the sky.

The professional Norman archers used short or Danish bows, and had advanced to within a 100 yards of the English lines before releasing their deadly hail of arrows.

The Normans advanced at a slower pace taking 30 minutes to reach the Saxon line which had by now begun to waver, break in places, and finally disintegrate under the Norman onslaught. Once a gap in the Saxon line had been created the Norman cavalry streamed through wielding their lances, swords and spears, caused mayhem in the reserve Saxon army. After 16h00 the breach in the lines had widened and fighting had degenerated into group actions with hand to hand fighting.

A large group had rallied around King Harold’s standard as he led his men with tenacity and courage setting a personal example for his Huscarls. However his remaining men were insufficient to repel the Norman onslaught. The turning point of the battle was when an arrow struck King Harold in or near his eye, wounding, but not killing him.

As Harold attempted to pull the arrow from his head, a group of Norman knights came upon him and cut him down with their swords. His brothers had already been killed in the battle.

The death of Harold himself while leading his few remaining Huscarls was the final blow and the news of his death spread quickly through the now straggling and much thinned English ranks. They broke up and fled, many of them pursued by the Normans including William himself, who was riding his fourth horse of the day, having already had three horses killed out from under him.

Both sides had lost over 2,000 men, which represented over a third of the Norman army. However for William, it was a triumph that finally paved the way for him to be crowned King of England on 25 December 1066.

Battle Abbey was founded in about 1070. In that year the Normans were ordered to do penance for the slaughter incurred in the conquest of England especially at the Battle of Hastings four years earlier. In this spirit, William the Conqueror vowed he would build an abbey at the site of the battle and the high altar would be placed on the spot where Harold had been killed.

He imported a team of monks from the Benedictine Abbey in France who had been invited to commence the building. However, on looking at the sloping site dipping down into marshland, the monks commenced building further to the west. William was furious that they had not carried out his orders, and the monks returned to France with order to source loads of grey – white stone from Caen, a city later to be destroyed by bombs and shellfire.

The monks returned to the site on the now levelled off ridge and commenced building. The first structure to rise was the abbey church with later additions consecrated by the archbishop of Canterbury in the presence of the Conqueror's son, William Rufus the 2nd.

Just as Bayeux was one of William the Conqueror's Normandy strongholds, so Portsmouth had been of prime importance in the defence of the English realm. On another D Day in 1944, Portsmouth was the last city in England seen by the many troops who sailed to France in the invasion fleet, and ironically Bayeux was the first major city to be liberated by the advancing Allies.

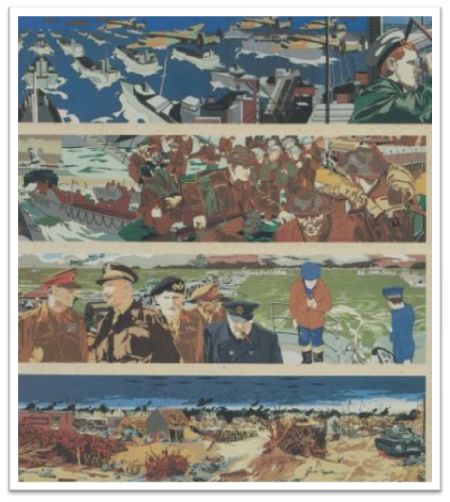

The Overlord Embroidery was commissioned by Lord Dulverton in 1968 as a personal tribute to those who fought and died in Normandy 24 years earlier. Commissioned from the Royal School of Needlework, the Embroidery was designed by artist Sandra Lawrence who worked on the design with senior officers from the three services and Ministry of Defence historians.

The key scenes were prepared by using wartime photographs and then converting them to full size drawings. Production details were meticulous, and included the matching of uniform fabrics, khaki uniform cloth, the actual fabric for a paratrooper’s beret and the gold braid for the uniform of King George V1.

The Embroidery with its 34 panels took embroiderers 5 years to complete. At 83 metres long by 1 metre high, it is the largest of its kind in the world; 12.5 metres longer than the Bayeux Tapestry. The display opened in the Portsmouth D Day Museum in April 1984 by the Queen Mother to coincide with the 40th anniversary of D Day.

The opening marked another cycle of history portrayed by connections, with illustrations and echoes of the past.

The embroidery moves on to include scenes from the Battle of the Atlantic and the Battle of Britain as depicted with WAAF plotters. The Women’s Auxiliary Air Force played a dynamic role serving as drivers, hot air balloon personnel, with some serving ferry pilots to transport new aircraft from factory to base, and transferring aircraft between RAF bases.

Panel 9 illustrates a meeting attended by the Supreme Allied Commanders taken on February 1st 1944 at Norfolk House. They are Lt Gen. Omar Bradley, Admiral Sir Bertram Ramsay, Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Tedder, General Dwight D Eisenhower, General Sir Bernard Montgomery, Air Marshal Sir Trafford Leigh-Mallory, and Lt Gen. Walter Bedell Smith.

On the evening of 5 June, Eisenhower was driven to the tented camp of the 502nd Parachute Regiment, the 101st Airborne at Greenham Common. The scene depicted on the embroidery shows Eisenhower talking with US Paratroopers prior to their jump into France in the early hours of D Day. He had an informal conversation with the men including Lt. Wallace Stroebel as illustrated on it.

It happened to be the 22nd birthday of the young officer who, although anonymous under the camouflage cream, is identified by his number 23 indicating he was one of the jumpmasters. He survived the war and later recalled that the Supreme Commander had asked him his name and where he was from.

Noting the concern on Eisenhower's face, one of the paratroopers commented, “Quit worrying General, we'll take care of this thing for you,” causing Eisenhower to grin. It was noted that as he turned away, his eyes were moist with tears. In his staff car he said to Kate Summersby his driver “I hope to God I know what I'm doing.”

Also included is Field Marshal Rommel who was responsible for the Normandy coastal defences. When the Allies landed on the 6th June 1944, he was away visiting his wife on her birthday, but on returning to Normandy, his staff car was attacked by a Spitfire and as a result of injuries sustained, had no further involvement in the campaign.

On panels 12, 13 and 14, the Allied Fleet sailing for France is headed by minesweeper flotillas and with aerial support by Spitfires of the RAF.

The Landing Ship carrying Lord Lovat`s Special Service Commando Brigade sailed from Portsmouth with his personal piper Bill Millin of the Cameron Highlanders standing on the bow in his battledress tunic and kilt playing “The Road to the Isles.” The sound carried across the water and the crews of the other ships began to cheer.

The captains of two of the Royal Navy's Hunt Class destroyers responded by playing “A Hunting We Shall Go” over their loud speakers, and not to be outdone, two Free French destroyers broadcasted their national anthem, the “Marseillaise.”

Panel 17 is a tribute to Piper Millen who is seen playing his pipes in the museum. Visitors to the exhibit wearing headphones will hear his pipes playing and his description of his experiences when standing opposite this panel.

On D-Day the Special Service Commando Brigade marched inland to relieve the glider troops commanded by Major John Howard. They were ordered to hold the bridgehead they had taken over the Caen Canal until relieved by Lord Lovat`s Commando`s who had advanced inland from Ouistreham.

At about midday the glider troops they heard the skirl of pipes of Bill Millen who lead the Commandos across what became known to this day as “Pegasus Bridge”.

Panel 22 shows troops landing on the beaches encountering beach obstacles known as “Rommel's Asparagus”, panel 24 depicts British troops landing on the designated Gold, Juno and Sword beaches. Clearly visible in the top right corner a Churchill “Flail" tank which was used to detonate mines as it advanced. Maj. Gen. Percy Hobart was Field Marshal Montgomery’s brother-in-law and was included in the illustrations. He was instrumental in developing these specialised armoured vehicles for specific purposes. Although offered to the US forces, they were rejected.

A post D-Day analysis indicated that had the US troops landing on Omaha Beach used the AVRE (Armoured Vehicle Royal Engineers); their landings would have been easier with reduced losses.

The total command of the air by the Allied air forces facilitated the success of D-Day and ahead. The Embroidery depicts a rocket firing Hawker Typhoon fighter bomber, one of the Allied aircraft responsible for limiting the daylight movement of German troops, vehicles and tanks. It was the most feared aircraft by German tank crews who nicknamed them “Jabo's” or Jagdbomben. It was fitted with eight 76.2mm rockets, four 20mm cannon or two drop bombs totalling 900kg.

The Black & White identification stripes painted on the aircraft were initially intended to differentiate from the German Focke-Wulf 190 that had a similar profile. Subsequently all Allied aircraft from D Day onwards were marked the same way.

Panel 28 depicts King George, General Eisenhower, Field Marshal Montgomery, General Alan Brooke, and Prime Minister Churchill visiting the landing beaches for the first time.

British and Canadian troops are shown penetrating the outskirts of Caen on the 9th July in panel 30. The town had been devastated by a continuous bombing campaign which in fact assisted the Germans defence from the ruins.

An accurate reproduction taken from a photograph of a young German soldier, one of many captured on D Day, is included in panel 34, which also includes The civilian casualties of war are depicted in the closing panel, with a group of French civilians mourning the death of one of their own.

Compared with William's landing in England in 1066, the landings in Normandy in 1944 did not go as planned, but however imperfect, one has to consider the repercussions had it failed, which would have resulted in the post war map and history of Europe being very different indeed.

The thanks of the meeting for two outstanding presentations were conveyed in appropriate manner by our Chairman, Roy Bowman.

Next Meeting:

Thursday 13th October 2016:

Darrell Hall Memorial Lecture: “The WW2 Arctic Convoys of William Foster” by Clyde Foster

Main Talk: “Bray Hill Revisited; the Anglo-Boer War laager west of Mooi River”, by Donald Davies.

(NOTE: The scheduled speaker (Maj Peter Williams) is unable to return from his current assignment in time to speak to us, so he will be rescheduled at a later date. Fellow Member Donald Davies has kindly agreed to replace him with very little notice, for which we are most appreciative).

Thursday 10th November 2016:

Darrell Hall Memorial Lecture: “General Patten in Sicily” by Maj Dr John Buchan

Main Talk: “The voyage of Admiral von Spee, Sept to Dec. 1914” by Robin Smith

Thursday 8th December 2016:

One lecture only, followed by the Branch’s annual cocktail function: “Another Aeroplane Crash in the Scottish Highlands”, by Ian Sutherland.

Thursday 19th January 2017 (NB THIS IS THE THIRD THURSDAY)

Darrell Hall Memorial Lecture: “The Indo-Chinese Soldiers at Clairwood Camp”, by Arthur Gammage.

Main Talk: “The Battle of Vaalkrans - defeat snatched from the jaws of victory”, by Ken Gillings

Meetings are held at the Murray Theatre, Department of Civil Engineering, University of KwaZulu-Natal Howard College Campus, Durban at 19h00 for 19h30.

End of Year Luncheon

Immediate Past Chairman Charles Whiteing is arranging the 2016 Branch annual luncheon at the Blue Waters Hotel, Durban, on SUNDAY 27TH NOVEMBER 2016.

This will be a special event, because it will commemorate the 50th anniversary of the founding of the South African Military History Society in Johannesburg in 1966.

Cost: R185 per person (R165 per person for pensioners).

Please contact Charles Whiteing on charlesw2@absamail.co.za or 0317647270 / 0825554689 if you’d like to attend.

A list is also being circulated at monthly meetings.

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org