Newsletter No. 490

December 2016

Our two speakers were Branch stalwarts Maj Dr John Buchan and Robin Smith. John's topic - entitled "Patton in Sicily" - was a continuation of the Patton legacy left by the late Professor Mike Laing and we were delighted to see Mary Laing in the audience.

Operation Husky, the invasion of Sicily, was decided on during the discussions of the Allied Chiefs of Staff at Casablanca in January 1943. The Americans were initially keen to proceed later that year, with a landing in Europe, to commence the assault against the Germans.

After discussion of all factors, particularly the logistics, the Americans accepted that the landing in Europe be delayed until around the spring of 1944.

The capture of Sicily would also open the Mediterranean to Allied shipping. At this stage, Allied convoys around the Cape and Durban were occurring. The Americans were also then sending supplies to China via the Middle East. Capturing Sicily could also well result in Mussolini's downfall and Italy withdrawing from the war.

The British 8th Army under General Montgomery and the American 7th Army under General Patton, were the military elements involved. The 7th Army was the first numbered American army to serve outside America. Patton's army in the Operation Torch landing had been the Western Force. Being a Combined Operation, Naval and Air Force support was also involved in this operation.

There was much preliminary discussion about where the military forces would be landed. The final 7th plan made in April was largely influenced by the ideas of General Montgomery. He advocated the landing of the 8th Army on the Eastern margin of Sicily. The large ports of Syracuse and Augusta could be occupied early, and the route up the east coast was to Messina, the port closest to the Italian mainland, and the key military objective.

The American forces were to be landed on an approximately 60 mile stretch of open beach with no large harbours. Montgomery envisaged the American Forces as a protection against enemy attack on his Western flank.

General Alexander consented to the American landings on the beaches after being impressed by the efficiency of the DUKW amphibious vehicles. This was the first operation in which they had been involved.

The much improved mobile radio sets also proved to be invaluable. The fact that Naval Ensigns on shore could rapidly arrange fire from the naval vessels, to the required areas was an important factor in the success of the landings.

At the time of the landings in Sicily, the Commander of the Axis Military Forces was General Guzzoni. He had been appointed in May 1943 at the end of the Tunisian campaign. He was 66 years old and came out of 2 years retirement.

Guzzoni soon realised the poor state of the 4 infantry divisions and the inadequate staffing and training of the troops for the Coastal Defence unit. They were also deficient in anti-naval and anti-tank guns. The 250, Axis personnel captured in the Tunisian campaign would compromise the defence of Sicily.

The two German Panzer units in Sicily were by comparison efficient and well equipped.

At this stage, although the Germans recognised the inefficiency of the Italian military, it suited them to support the Italians. This would be a lesser task than filling the vacuum if Italy withdrew from the war.

The Allied landings commenced with the dropping of paratroopers, some in gliders, in the early hours of 10th July. The date of the invasion had been chosen because of the favourable phases of the moon that would assist the paratrooper activities.

The poor navigation skills of the pilots, both in the RAF and the American 8th Air force, greatly compromised the effectiveness of this operation.

Landings of the troops commenced on the morning of the 10th. The DUKW amphibious vehicles proved invaluable. The British landings were initially unopposed.

On the first two days, Patton's troops were attacked by tanks from General Conrath's Herman Goring Panzer unit. Patton, who had landed a scout car, was personally involved in co-ordinating the defence against the Panzer units. The beach landings were duly consolidated and inland movement commenced.

By the 14th July, the Germans had appreciated that the Allied invasion force could not be dislodged. Limited further German forces were to be sent to Sicily to bolster Italian morale, and to buy more time by organising a controlled withdrawal from the North Eastern section of Sicily, aided by the mountainous terrain around Mt. Etna.

General Hube's XIV Panzer Corp headquarters was moved to Sicily. He was then to be in charge of all German and Italian troops. He was also instructed to save as many German troops, and as much German equipment as possible during the staged withdrawal. This was imperative in view of the tank battles, including Kursk, then proceeding on the Eastern Front, and losses sustained in Tunisia.

After the progression inland following the beach landings, the Allies linked up along a common front on 13th - 14th July. No further detailed planning had been done.

As Montgomery at this stage, was beginning to encounter resistance along the coastal road on the eastern margin of Mount Etna, he requested Alexander to allocate Highway 124 which skirted the western edge of Mount Etna, to his forces. Highway 124 had initially been in the US zone. Alexander acceded to this request and again stressed to Patton, his role of guarding the British western flank.

Patton felt this ongoing passive role was an insult to the fighting capabilities of his army.

After further discussions with Alexander, Patton duly received permission to mount armed renaissance patrols towards Palermo.

Patton interpreted this liberally, and on the 19th July, arranged for his chief of staff General Keyes to commence a move to Palermo. With the logistics well organised, Palermo was reached within 4 days. The rapidity of this move had been very impressive.

At this stage, the movement of German troops to the North East region of Sicily had already commenced, and none were encountered. Many Italian prisoners were taken. Those from low grade units were released to the care of the local population.

The large harbour at Palermo had escaped significant damage. In Palermo, Patton stayed in the King's bedroom in the ancient castle, built soon after AD 1000, by William I, an early Norman King.

Patton was now in a position to proceed along the northern coastal road, with Messina as the goal. At the commencement of this move, Patton received a letter from Eisenhower, urging him to reach Messina as soon as possible. The move towards Messina was frustratingly slow, with the terrain favouring the defenders.

Patton had great empathy with the wounded troops, and often visited the base hospitals with a supply of Purple Heart medals. It was on the 3rd and 10th of August, that at visits to Base Hospitals, when Bradley's Corp was attempting to take Troina, the highest settlement in Sicily and a key defence point on the German defence line, that the notorious slapping incidents occurred.

Amongst the wounded soldiers, on each occasion, a soldier with no wounds, was present. During the second incident, Patton's histrionics were at a higher level, and the Medical Officer in charge sent in a formal complaint to Eisenhower. The pressure on beating Montgomery into Messina was a factor.

As well as the military efforts along the northern coastal road, Patton also attempted to outflank the German defences by carrying out 3 sea-borne landings. The first was successful, the second was anticipated by the Germans and the third landed in front of the retreating German forces.

The German forces had progressively retreated to prepared rear defence posts.

On the 10th August, Hube announced that the German evacuation would commence on the 11th. On the 10th, he had induced General Guzzoni to move with his 6th Army headquarters to Calabria, the site on the Italian mainland, adjacent to the ferry. The Italians operated their own ferry service, alongside the very efficient German ferry service run by the German Officer Baarde. The efficiency of his service contributed greatly to the successful Axis evacuation.

The Germans had evacuated not quite 40,000 men of whom almost 4,500 were wounded; 9,600 vehicles; 94 guns; 47 tanks; 1,000 tons of ammunition; 970 tons of fuel; 15,700 tons of miscellaneous equipment, including much Italian material.

The Italians, whose records were not quite so well kept, had ferried between 70,000 and 75,000 troops across; around 500 vehicles; between 75 and 100 artillery pieces and 12 mules. Hube and fellow Panzer commander Fries, left Messina at 5:30 pm on 16th August.

Several hours before midnight on 16th August, a reinforced platoon of the US 3rd Division, entered Messina, and early the following morning the troops followed.

At 10:00 am that morning, Patton officially accepted the formal surrender from the local authorities.

The first British commandos entered Messina around 08:15 after discovering the withdrawal of the German forces. They congratulated the Americans on narrowly winning the race.

After reviewing the documentation on the slapping incidents, Eisenhower wrote a personal letter to Patton, requesting him to make an apology to the troops involved. On 22nd August he addressed the First Division troops in the area in front of the palace and explained his actions. Eisenhower was keen to avoid publicity of this incident and addressed the local newspaper correspondents. They all agreed not to file reports on the matter.

General Alexander was aware of the incident and regarded it as an internal issue for the Americans to resolve.

In his memoirs, he mentioned that he had expected Patton to be made commander of the American Army being prepared to land in Italy. At this stage, information on these incidents had reached the American High Command in Washington who were doing their best to suppress the issue. Some relevant Congressmen were also aware of the incident. In this situation, it was decided that it would be unwise for Patton to be given command. The command of the American 5th Army was then given to General Mark Clarke, relatively inexperienced in field command.

When the Salerno landing, south of Naples duly occurred, Vice Admiral Kent, in charge of the American landing fleet, soon reported to General Alexander that events were not proceeding favourably. (Kent had previously landed Patton in Casablanca and in Sicily). Alexander then made repeated requests for Patton to be placed in Command. No change was made and the Salerno landing later stabilise.

In November 1943, a military source in Washington informed Drew Pearson who ran a radio chat show. The incident then received nationwide publicity. Eisenhower was however, determined to maintain Patton on his staff. He was duly posted to England to take charge of the 3rd Army, which was to be involved in the Normandy activities.

In February 1943, difficulties again occurred in the Italian Campaign. General Clarke had made a poor choice of the General in charge of the Anzio Landings, which also involved British troops.

When informed by Alexander, Eisenhower was very concerned about the possibility of the landing needing to be aborted. After discussion with Churchill and General Brooke, Eisenhower got their support for Patton's involvement at Anzio.

On 16th February, Eisenhower informed Patton that he was to be dispatched to Anzio for a month in order to stabilise the situation. He was to leave the following afternoon, together with the staff he had selected.

When Eisenhower released this order to all military staff concerned, this was strenuously resisted by General Clarke, who proposed General Truscott to take command at Anzio.

After due reflection Eisenhower agreed with Truscott taking command, and Patton duly continued his preparations for Normandy. He always had the feeling that destiny would lead him in the right direction.

Robin Smith's topic for the Main Talk was entitled "The Voyage of Admiral Graf von Spee". Admiral Graf Maximilian von Spee's East Asia Squadron, based in the German colony of Tsingtao in China, needed to seek sanctuary on the outbreak of war in 1914. How they managed to cross the Pacific Ocean, only for the Royal Navy to catch up with them in the southern Atlantic at the Falkland Islands is a remarkable story.

The German colony of Tsingtao on the Yellow Sea was created to provide a base for a cruiser squadron of the Imperial German Navy. By 1914, the city's brick houses and red-tiled roofs were reminiscent of central Europe. There were the Christ Church with its towers and the station of the Shantung Railway - and of course the famous Tsingtao brewery.

The German East Asia Squadron consisted of two armoured cruisers, Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, sister ships of 11,400 tons, launched in 1907, carrying 8.2 inch guns of 22 knots and three modern light cruisers, Emden, Leipzig and Nürnberg, 3,500 tons with 4.1 inch guns of 25 knots. Their function was to police the Kaiser's possessions in the Pacific - the Marianas, the Carolines, the Marshall Islands and Samoa.

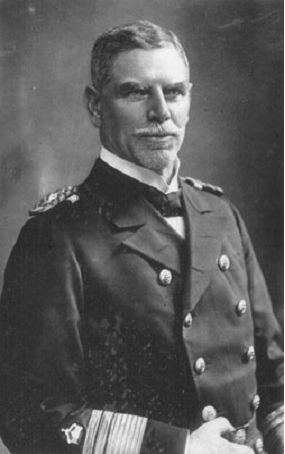

Vice-Admiral Graf Maximilian von Spee

Vice-Admiral Graf Maximilian von Spee was born in Copenhagen in 1861, tutored in a family castle, and entered the navy at the age of 16. He was a gunnery specialist and in November 1913 he was promoted Vice-Admiral and sent to command the East Asia Squadron.

In June 1914 the British Far Eastern Squadron paid a courtesy visit to Tsingtao and were welcomed in Tsingtao harbour. The British officers were entertained on Gneisenau and British sailors competed with Germans in relay races, boxing matches, soccer and a tug-of-war. "The brotherhood of the sea" was invoked in speeches and toasts. Shortly after the Royal Navy visit the Germans set out on a three month cruise through the islands of the Pacific. At Saipan, the capital of the German Marianas, they learned of the assassination of the Archduke Frans Ferdinand. On 6th July they entered the vast Truk lagoon and a message from Berlin warned that "the political situation is not entirely satisfactory."

Spee decided that he would await developments at Pohnpei, 400 miles east of Truk. On 27th July the Berlin Naval Staff sent news of Austria's ultimatum to Serbia. Before leaving Pohnpei, Spee had been informed that Germany was at war with Britain, France and Russia. Britain's ally, Japan, declared war on 23rd August. To the east, across the Pacific, was the coast of South America. There were neutral nations all the way from the southern border of Canada to Cape Horn who would sell him coal and perhaps he could find his way around the Horn and into the Atlantic.

Gneisenau and Scharnhorst each had a capacity of 2,000 tons of coal. Steaming at 10 knots each ship burned 100 tons a day, however, at 20 knots the figure was 500 tons. As a general rule no captain would allow his bunkers to fall lower than half-full. Thus Spee would need a coaling stop every eight days. On 13th August Spee called his captains together and told them what he proposed. Captain Karl von Müller of the Emden, the fastest and most modern of the light cruisers, was detached to head into the Indian Ocean.

Emden began a marauding career that resulted in the sinking of 16 British and neutral merchantmen, a Russian cruiser and a French destroyer, as well as the destruction of the Burmah Company's oil tanks in Madras. On 9th November she was caught and destroyed by the Australian cruiser Sydney, driven onto a reef, burning and wrecked. Müller was the most successful commerce raider of the Great War.

The Nürnberg was sent to Honolulu to pick up newspapers and send a cable to Berlin. She rejoined them at Christmas Island and brought news that New Zealand troops had occupied Apia, the capital of German Samoa. When the Germans approached the island's anchorage of Apia on 14th September they found it deserted but an attempt to recapture the island would have been costly in ammunition and casualties so the Germans sailed away without firing a shot.

Spee heard the Apia wireless station broadcasting his position, and first turned and steamed away to the northwest. Then when well clear of the land he turned east once more. The British concluded that he was on his way back to China. The two cruisers next anchored off Bora Bora, displaying no national flag. The French authorities met only officers who spoke English and the Germans paid in gold for coal, pigs, poultry, eggs, fruit, vegetables and fresh meat. As the cruisers weighed anchor and sailed out of the lagoon, the French hoisted a large French flag - the Germans, in reply, raised the German naval ensign. French artillery exchanged shots with the German gunners at Papeete but by 30th September the news of his attack on Tahiti reached London.

The next objective was Easter Island. The island had no wireless and thus the islanders knew nothing of the world war. The Germans were supplied with fruit and vegetables and boatloads of beef and mutton. The German light cruiser Dresden, 3,000 miles away which had come around the southern tip of South America from the Atlantic joined them at Easter Island. Dresden signalled that she was probably being followed by the British armoured cruisers Good Hope and Monmouth. A British wireless station at Suva in the Fiji Islands intercepted the message and passed it on to London. The Admiralty was now provided with the East Asia Squadron's position and its destination. The Germans left for the Juan Fernandez group of volcanic islands, 450 miles from the Chilean coast.

Leipzig arrived after her cruise to North America. After a few days at Robinson Crusoe's island the squadron moved to within 50 miles of the port of Valparaíso. Spee had successfully crossed the great ocean but he had caused no military damage. He had steamed 12,000 miles through tropical heat with no engine trouble, he had kept them supplied and kept up the morale of his men. Apart from the Emden, the squadron had done little to contribute to the German cause.

A powerful force of enemy ships had vanished into the immensity of the Pacific Ocean. Taking the Caroline Islands as the centre, in London they drew daily widening circles touching more and more points where Spee might spring into action. Important to the Admiralty was the protection of British trade in the North and South Atlantic. Two German light cruisers, Dresden and Karlsruhe, were in Port-au-Prince in Haiti in July 1914. Rear Admiral Sir Christopher Cradock was commander of the Royal Navy's West Indies Station. An obsolescent cruiser Good Hope was his flagship. Cradock's orders were to move down the coast of South America, find Dresden and sink her.

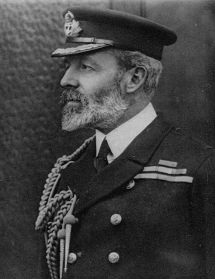

Rear Admiral Sir Christopher Cradock

By the time Cradock and his squadron reached the River Plate, Dresden had rounded Cape Horn. Cradock's orders from the Admiralty warned him about the Scharnhorst and Gneisenau off the coast of Chile. A reinforcement, an old battleship, Canopus, which was due to be scrapped in 1915 was on its way. He was to make the Falkland Islands his primary coaling base. The Admiralty considered that with Canopus, Good Hope and Monmouth, his two armoured cruisers and a modern light cruiser, Glasgow, he had adequate strength.

When Spee had left Samoa sailing northwest, the Admiralty assumed that he was returning to China. Cradock's orders required him to pass into the Pacific as the only enemy ship he was likely to meet was Dresden. London had now received from the British radio station at Suva in Fiji the intercepted message from Scharnhorst that the German squadron was steaming east towards Easter Island. Winston Churchill, First Lord, and Prince Louis Battenburg, sent orders to Cradock to concentrate Canopus, Monmouth and Good Hope at the Falklands Islands and send Glasgow to look for Dresden. The Admiralty assumed that the old, slow battleship Canopus, but with 12 inch guns, would enable Cradock to have superiority over Spee. Canopus had to repair leaking condensers and clean her boilers. Cradock sailed in Good Hope on 22nd October ordering Canopus to follow when she was ready.

Cradock was 52 years old and had been in the navy for nearly 40 years. In 1900 as an officer in the China Squadron, when the Boxer Rebellion broke out, he went ashore with the naval brigade to capture the Taku Forts. The Navy was his life. For him "the navy was not a mere collection of ships, but a community of men with high purpose."

Churchill admitted that he had been "gravely distracted" by the Admiralty upheaval over the departure of Battenburg and the arrival of Fisher. Prince Louis Battenburg was forced to resign as First Sea Lord after a press campaign against the Admiralty. After he left the Admiralty came the news that Vice-Admiral Maximillian von Spee had inflicted on the Royal Navy its worst defeat in over a century. Prince Louis's replacement was the 73-year old Admiral Jack Fisher.

Spee decided to attack and destroy his relatively small enemy, Glasgow. Each admiral believed himself to be pursuing a single light cruiser. Sunday 1st November was a clear early-spring morning and soon Glasgow identified two four-funneled German armoured cruisers. Cradock had not expected to meet the German squadron. Spee's sixteen 8.2 inch guns were opposed only by the two 9.2 inch guns of Good Hope. Scharnhorst's salvos were soon hitting Good Hope and Monmouth was taking hits from Gneisenau as the German salvos thundered out at 20 second intervals. Gneisenau's execution of Monmouth became terrible. Good Hope too was in a forlorn condition and by 7:50 p.m. the British flagship slid down into oblivion. Glasgow was in action against the two German light cruisers but managed to survive. Churchill described Coronel as "the saddest naval action of the war." Sixteen hundred British seamen had died, Christopher Cradock was one of them. Five German sailors had been wounded.

On 3rd November, Scharnhorst, Gneisenau and Nürnberg entered the bay of Valparaíso. The German population of Valparaíso was enthusiastic. Admiral von Spee and his officers visited the German Club. The admiral was polite until a "drunken, mindless idiot raised a glass and said, 'Damnation to the British Navy!'" Spee gave him a cold stare and said that neither he nor any of his officers would drink to such a toast. Instead, he said, "I drink to the memory of a gallant and honourable foe," put down his glass, picked up his cocked hat and left the club.

In London the Admiralty received the first news of the disaster at Coronel on 4th November. Within six hours Lord Fisher sent Invincible and Inflexible to the South Atlantic. The hunting down and destruction of enemy armoured cruisers was the purpose for which Fisher had designed and built battle cruisers. Combining high speed and big guns, the dispatch of two of them to the South Atlantic was meant to ensure not merely Spee's defeat, but his annihilation. A Vice-Admiral was needed to command the new force and Sir Frederick Doveton Sturdee was appointed. He had entered the navy at twelve, specialized in gunnery and torpedoes and had a reputation as a tactician.

Fisher realised that Canopus she would be useless in a sea battle and ordered her to run herself aground at Port Stanley, transforming herself into a stationary steel fort. The British ships arrived at Port Stanley on Monday morning, 7th December. After his victory, Admiral Spee learned that Tsingtao had fallen and that Emden's voyage had come to an end. Cradock had significantly weakened their fighting power by depleting their magazines. Spee learned from a collier that there were no British warships in the Falkland Islands. Gneisenau and Nürnberg were to proceed to Port Stanley, enter the harbour, destroy the wireless station and burn the coal stocks. As Gneisenau and Nürnberg< drew closer, Canopus was invisible to the Germans and her 12-inch guns spoke first. The shots fell short but the two German ships rejoined Spee at full speed.

Inflexible and Invincible came out of the harbour and their speed climbed to 25 knots. Sturdee could see the smoke from the five fleeing ships and he knew that, barring some wholly unforeseen circumstance, Spee was at his mercy. Each British battle cruiser carried eight 12-inch guns, firing shells weighing 850 pounds. The German armoured cruisers carried eight 8.2-inch guns, firing shells of 275 pounds. Sturdee could use his speed to set the range, then keeping his distance, use his big guns to pound Spee to pieces. Sturdee was so confident of the day's outcome that at 11.30 a.m. he signalled, "Ship's company have time for next meal."

At 12.47 p.m. Sturdee hoisted the signal "Engage the enemy". Within 15 minutes tall splashes began straddling the German ships. Invincible trained on Scharnhorst and Inflexible on Gneisenau. Both German ships were severely damaged. Scharnhorst stopped firing and went down, her flag still flying and her propellers turning in the air. Every one of the 800 men on board, including Admiral Spee, went down with her. Gneisenau was subjected to an hour and a half's target practice by the two British battle cruisers and submerged so slowly that men on deck were able to climb down the ship's sides as she heeled over. The sea temperature was 39°F and the British ships made every effort to pick up the survivors. Carnarvon picked up 20, Invincible 108 and Inflexible 62 among whom was Commander Hans Pochammer, second-in-command. Invincible had two wounded and Inflexible one killed and three others were wounded.

The last word must be Churchill's. "At 5 o'clock in the afternoon I was working in my room when Admiral Oliver entered with a telegram from the Governor of the Falkland Islands: 'Admiral Spee arrived at daylight this morning with all his ships and is now in action with Admiral Sturdee's whole fleet, which was coaling.' These last three words sent a shiver up my spine. Had we been taken by surprise and, in spite of all our superiority, mauled, unready, at anchor? 'Can it mean that?' I said to the Chief of Staff. 'I hope not,' was all he said. I could see that my suggestion, though I hardly meant it seriously, had disquieted him. Two hours later, however, the door opened again, and this time the countenance of the stern and sombre Oliver wore something which closely resembled a grin. 'It's all right, sir, they are all at the bottom.' And with one exception so they were."

Our Chairman, Roy Bowman, conveyed the thanks of the audience to both speakers for their superbly researched and prepared presentations.

Next Meeting:

Thursday 8th December 2016:

One lecture only, followed by the Branch's annual cocktail function: "Another Aeroplane Crash in the Scottish Highlands", by Ian Sutherland.

Note that Fellow Member Peter Schneider has arranged for an estate to treat us to wine tasting but members are requested to bring along their own glasses and refreshments should they not wish to partake. The Branch will provide snacks.

Thursday 19th January 2017 (NB THIS IS THE THIRD THURSDAY)

Darrell Hall Memorial Lecture: "The Indo-Chinese Soldiers at Clairwood Camp", by Arthur Gammage.

Main Talk: "The Battle of Vaalkrans - defeat snatched from the jaws of victory", by Ken Gillings

Thursday 9th February 2017 (NB - Reverting to the SECOND Thursday)

Darrell Hall Memorial Lecture: "South Africa's last Colonial Exploit", by Professor Philip Everitt.

Main Talk: "The Struggle for South Africa", by Donald Davies.

Thursday 9th March 2017

Darrell Hall Memorial Lecture: "The South African Medical Corps in WW1" by Lt Col Dr Graeme Fuller

Main Talk: "Deelfontein" by Dr Arnold van Dyk

Meetings are held at the Murray Theatre, Department of Civil Engineering, University of KwaZulu-Natal Howard College Campus, Durban at 19h00 for 19h30.

End of Year Luncheon

Immediate Past Chairman Charles Whiteing is arranging the 2016 Branch annual luncheon at the Blue Waters Hotel, Durban, on SUNDAY 27TH NOVEMBER 2016.

This will be a special event, because it will commemorate the 50th anniversary of the founding of the South African Military History Society in Johannesburg in 1966.

Cost: R185 per person (R165 per person for pensioners).

Please contact Charles Whiteing on charlesw2@absamail.co.za or 0317647270 / 0825554689 if you'd like to attend.

A list is also being circulated at monthly meetings.

We trust that all our Members and Friends will have a safe and peaceful Festive Season and a prosperous 2017. We look forward to seeing you at our last meeting of the year on the 8th December 2016, and the first meeting of the New Year on the THIRD THURSDAY of January 2017.

South African Military History Society / scribe@samilitaryhistory.org