Our speaker on 11 February 2016 was Rear Admiral (JG) André Rudman SAN (Ret), whose topic was the history of the Martello Towers in the Mediterranean, England and South Africa.

Over the centuries, round stone or brick towers had been constructed along the Mediterranean coastline and especially the islands, usually on prominent capes or headlands, to be used as lookout points to give warning of the approach of enemy ships, including pirates. The population would be warned by the lighting of fires on top of the towers and, along the Western shores of Italy, striking a large bell with a hammer (or “Martello”). So these towers became known as “Torri di Martello”. The earliest towers were built by the Phoenicians.

By the end of the 16th century and in the early 17th century, the problem of piracy had become a lot more serious. The reason was that the people of North Africa had broken away from the Ottoman Empire and had taken to piracy on a large scale. They were known as the Barbary Pirates, who operated mainly from Tripoli, Tunis, Algiers, Bone and Salli, which became military republics living largely from piracy. They became the scourge of the Northern coast of the Mediterranean and the islands along that coastline. They even raided along the Atlantic coast of the Iberian Peninsula and as far as Ireland and England.

At first they used Galleys and then graduated to the use of sailing ships, especially in the Atlantic. They looked for loot, women for their harems and males to work their fields and row their galleys. They even raided Baltimore on the coast of Ireland in 1831, enslaving most of the population and selling them in Algiers. Some 40 000 Christians were sold into slavery in Algiers and Tunis during the first half of the 17th century alone.

The various European navies spent a lot of time and effort in trying to stop their raiding. Even the fledgling United States lost ships to them. On 31 October 1803 the USS Philadelphia, a 36-gun frigate, ran aground outside the harbour of Tripoli. Her captain surrendered and he and his crew were sold into slavery. The Tripolitanians refloated the ship but she was burnt at her moorings in a daring raid led by Lt Stephan Decatur on the night of 16-17 October 1804.

The Americans blockaded and bombarded Tripoli and then tried a landward attack by capturing Derna, an important port. Seven US Marines and 400 other men were landed and they marched along the coast towards Tripoli, supported by the US ships Argus, Nautilus and Hornet. The Pasha appreciated the danger and proposed that a ransom of 60 000 dollars be paid for the crew of the Philadelphia. This was done and the US Marines had fought their first action on foreign soil. This was commemorated in their famous march “From the Halls of Montezuma to the Shores of Tripoli”. Adm Rudman had recorded this for us.

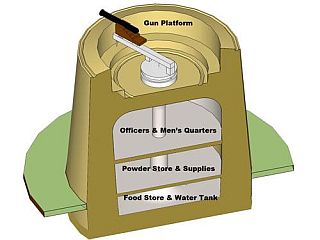

It can be appreciated that the Mediterranean area in the period of the 16th to the mid- 19th centuries was a very turbulent one. There was a great need for coastal defences and look-out points all along the Mediterranean coasts and Islands to protect the population. The towers near to the coast were now being constructed with very thick stone walls (or in some cases, of brick) with a flat roof on which were placed one or more cannon. The most common height was 12m [+/40 feet] with the lower part of the wall 2,4m to 3,4m (8 to 11 feet) thick. There were usually two floors inside with a powder magazine and water tank below the first floor. Access was via a door set at first floor level, using a ladder. This was taken into the tower when the door was closed, so the towers were not easy to capture. Lookouts on the tower would light a signal fire if they sighted an unidentified ship or ships approaching. Our speaker showed us pictures of a number of these towers. Many towers were built by the Genoese who were an important power in the 1500’s. They purchased Corsica in 1562 and proceeded to build some 80 towers along the coast of the island, at the same time upgrading all of the island’s defences.

We come now to the 18th century. In 1764, the Genoese asked the French to reoccupy the parts of Corsica which they had garrisoned in 1756. The Corsicans also asked France to recognize the independence of Corsica in return for payment equivalent to that paid to the Genoese. Nothing had been decided by 1793 as the French Revolution interrupted the negotiations.

On 1 February 1793, the French Convention, which was already at war with Austria, Prussia and Sardinia, declared war on Great Britain and Holland. The leader of the Corsican patriots, Genl Paoli, asked the British Government for help to liberate Corsica.

British ships were sent to blockade the northern parts of Corsica and to establish a safe anchorage there for future operations. The British squadron consisted of 3 line-of-battle ships and 2 frigates. The only safe anchorage available was the Gulf of San Fiorenza. This was protected by three very old towers which were armed and manned. The most important of these was the one on Mortella Point, named after the wild myrtle which grew in profusion on the point. The tower on Mortella Point was bombarded by HMS Lowestoft and the garrison forced to surrender. A garrison of Corsican patriots took over the tower - temporarily - as they could not prevent the French from recapturing it.

In February 1794 Admiral Lord Hood launched a new attack on the island and his first objective was to recapture the tower on Mortella Point. This proved to be difficult. His ships HMS Fortitude (74 guns) and HMS Juno (32 guns) had to withdraw after suffering heavy damage and losses of 6 dead and 54 injured.

The army, under Lt Col John Moore (who became famous during the Peninsular War of 1808-1814)1, were landed and it took them two days to capture the tower. The garrison surrendered because of a fire which luckily started in some rubbish on the parapet of the tower. The effectiveness of this inexpensive watch-tower fortification made a deep impression on officers, who, in years to come, became very well-known and who played a prominent role in designing the coastal defences of England, when the threat of invasion by Napoleon became all too real. These included Vice Admiral Sir John Jervis, Rear Admiral George Elphinstone and Major General David Dundas.

Section of Martello tower

As a result many of the defences then built were based on the Martello Towers they had seen in the Mediterranean, so named because of the hammer or “Martello” used to strike a bell in the tower as a warning. The British built some 140 towers round the south and east coasts of England in a very short time. However, these precautions proved to be unnecessary as the expected invasion never took place.

Corsica was eventually taken where the future Lord Nelson lost an eye at Calvi. Martello towers were built in various places by the British – in the West Indies, Ireland, Canada, the Channel Islands, Australia, Sri Lanka, Minorca, Indian Ocean, as well as South Africa. They were never tested in action and were later used as Coastguard stations to combat smuggling. As said a number of the English, as well as some Irish, towers survive. Some were restored, some are in ruins and some were used for housing. As our speaker commented, living in one of these will provide some peace of mind as the inhabitants need not fear to ever suffer storm damage.

The French built numerous towers, using the Martello tower as a pattern. These were used as signal towers which used a form of semaphore to pass messages back and forth over the length and breadth of France.

Our speaker then discussed the South African towers. In 1795, the British captured the Cape of Good Hope. Their forces were under the command of Admiral Elphinstone (later Lord Keith), and Major Generals Dundas and Craig. After capturing the Cape, the British set about repairing and upgrading the defences of the Cape. As part of this process, two towers, based on the Martello tower, were constructed in 1795.

One of these was the Simon’s Town tower which was built behind the Dutch Boetselaar battery. This has a height of 7,6m/25 feet, a base diameter of 13m/42 feet and walls 1,9m/6 feet thick. It has two floors and the entrance was on the ground floor. It had three gun ports facing inland to cover against any attack from the landward side and had place on the roof for a gun facing out to sea. It was never armed but also covered the powder magazines which contained 980 barrels of gunpowder. The tower had a wooden machicolated gallery2 above the door from which riflemen could fire on anyone attempting to enter the tower. Its design was based on the Martello tower but modified as required by its position in a battery.

Simon's Town Martello tower

The second was Craig’s Tower, constructed behind a battery on Salt River beach to guard against a possible attack along the coast from the north. Its function was similar to that fulfilled by the Simon’s Town tower and was presumably very similar in design. Both were built of stone, only the outside being dressed and the walls were vertical. With the expansion of Cape Town in the 19th century and the construction of more modern coastal defences, the battery and Craig’s Tower were demolished more than a century ago.

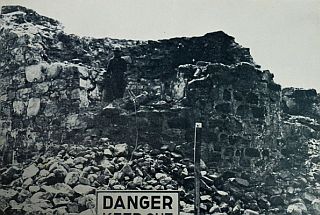

By the 1950’s part of the Simon’s Town Martello tower had collapsed.

Simon's Town Martello tower ruins.

A restoration campaign was started in 1936 by a former mayor of Simon’s Town, Mr W Runciman, but this was unsuccessful. Then, in 1960, the Simon’s Town Historical Society was formed. Their attempts to restore the building, though inadequate, were supported by the SADF. It was rebuilt and converted into a Naval Museum, which was opened in 1973. This museum was closed in 1993 and the exhibits were moved to the new Museum in the West Dockyard.3

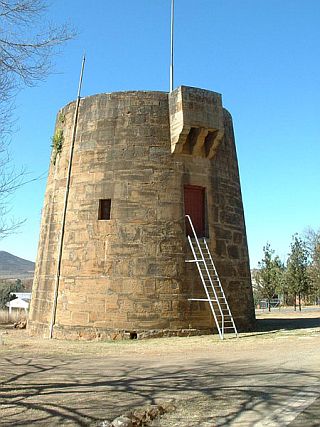

The third Martello Tower built in South Africa is the one at Fort Beaufort in the Eastern Cape. This is the only one not built within 3,2km/two miles of the sea or on a navigable inland waterway connected with the sea. The construction of this tower was started in 1837 as part of the system of military roads, forts and bridges authorized by Sir Benjamin D’Urban after the 1835 Frontier War, to link Grahamstown with the Winterberg. The Victoria Bridge in the town dates from the same time. A second tower was proposed for Grahamstown but this was never built. The Fort Beaufort Tower was completed in 1843 and is 9,5m/31 feet high, has a base diameter of 9,8m/32 feet and walls 1,9m/6 feet thick. The entrance door is 4m/13 feet above ground and there are four firing ports on the second floor. A gun could be mounted on the roof. There were a number of smaller towers along the Kat River and elsewhere, each with a cannon on its roof, which were quite useful when used against cattle rustlers.

The tower is in good condition and is now part of the Fort Beaufort Museum.

Fort Beaufort Martello tower

Our Vice Chairman, Mr Alan Mountain, thanked Adm Rudman for another fascinating talk and congratulated him on the excellence of his illustrations, before presenting him with the customary gift.

1 As Lt-Gen Sir John Moore, KB, he met his death at the Battle of Corunna on 16 January 1809 in which he defeated a French army under Marshal Soult during the Peninsular War.

2 A projecting gallery at the top of a wall of a fortification, supported by a row of corbels and having openings in the floor through which attackers could be taken under fire by the defenders.

3 The Tower can be visited on weekdays by prior arrangement with the staff of the S.A. Navy Museum.

FORTHCOMING MEETINGS

NB. - PLEASE NOTE CHANGE OF DATE – NB.

WEDNESDAY 9th March 2016: 75 YEARS OF SOUTH AFRICAN RADAR: BASIL SCHONLAND’S CHALLENGE by Dr B.A. Austin

Early in 1939 The British Government informed its Dominions - Canada, Australia, South Africa and New Zealand - of the existence of ‘certain technical developments which are of vital importance against air attack .…’ This was the top-secret device then known as RDF which would later become Radar. The work in South Africa on developing radar sets were led by Dr Basil Schonland, professor of geophysics at Wits, and Mr G R Bozzoli, a lecturer in electrical engineering. Basil Schonland was South Africa’s foremost physicist at the time and also a close colleague of many of those British RDF pioneers having studied and worked alongside them at Cambridge. He assembled a team of academics from the Witwatersrand, Cape Town and Natal universities to assist in the endeavour. The first local radar transmitter was cobbled together, as was the receiver, from electronic bits and pieces purchased from local electronic shops catering for radio amateurs. On the 16th December, 1939, the first radar echo was received in South Africa. From start to first successful transmission, a mere three months had elapsed.

In time the fledgling research group were soon joined by many other young engineering graduates from those universities mentioned, as well as from Schonland’s own research institute, the Bernard Price Institute of Geophysics Research. This group ultimately became the Special Signals Services (SSS) of the South African Corps of Signals in 1941. By then they had already set up and operated the first radar set to be deployed anywhere in Africa. It went into service near Mombasa in support of the South African forces in East Africa who were driving Mussolini out of Abyssinia. From there the SSS took three of their radars to the Sinai and provided early warning against air attacks on the Suez Canal. Soon it became apparent that the promised British radars intended to protect South Africa’s very long coastline were long overdue so the SSS set about designing its own protective radar screen that eventually resulted in more than twenty radar stations being established from Baboon Point in the west to just south of the Mozambique border in the east. Most of those radar sites were ‘manned’ by women who were trained at special radar schools in the major centres. By the war’s end in 1945 the SSS consisted of 145 officers, of whom 28 were women, and 1,476 other ranks (507 women). This small band of highly qualified university graduates, in the main, eventually served with great distinction throughout South Africa, in East and North Africa and in Italy. In addition, a special SSS detachment was attached to the SAAF where they fitted and maintained radar sets in the Wellington bombers of 26 Squadron then serving in Takoradi on the Gold Coast. This is their story.

The talk will cover the subject of radar; the remarkable personalities who designed and built their own sets in South Africa and of its operational performance in many theatres of war.

Our Speaker is formerly from the Department of Electrical Engineering at Wits University and now retired from the Department of Electrical Engineering & Electronics at the University of Liverpool. He lives in England.

PLEASE NOTE: IN VIEW OF OUR SPEAKER’S SHORT STOP-OVER IN CAPE TOWN, HE WILL NOT BE AVAILABLE FOR OUR REGULAR SCHEDULED MEETING ON THE 10TH OF MARCH. TO ACCOMMODATE DR BRIAN AUSTIN, THE MEETING WILL BE ADVANCED BY ONE DAY AND ARE NOW SCHEDULED FOR WEDNESDAY, THE 9TH OF MARCH – SAME TIME, SAME PLACE.

THURSDAY 14th APRIL 2016: The Speaker and Subject will be announced closer to the date.

BOB BUSER: Treasurer/Asst. Scribe

Phone: 021-689-1639 (Home)

Email: bobbuser@webafrica.org.za

RAY HATTINGH: Secretary

Phone: 021-592-1279 (Office)

Email: ray@saarp.net